Big In…

These six up-and-comers have built their businesses in far-flung corners of the world. Could they be the next big names in global luxury?

Related articles

A few names reign supreme when it comes to luxury—and you know who we’re talking about. They tend to be based in Western centres of commerce and design: New York City, Paris, London, and Switzerland, to name a few. But a new wave of stars across disciplines have honed their talents in more far-flung locales and are on the cusp of conquering the U.S. market. From Australia to India, China, Lebanon, and Turkey, these six up-and-comers are primed to have a breakout year on the global stage.

AUSTRALIA| Patrick Johnson

Patrick Johnson knows all about the tyranny of distance. When we meet in late January, the Sydney-based designer and tailor behind the P.Johnson label has just returned from a month of skiing in Verbier with family and friends. He is home for a microsecond before jetting off to do a photoshoot in London, attend a trade fair in Milan and visit suppliers in Tokyo.

“I’m usually on the road for at least four months of the year,” he says, enjoying a temporary respite in a downstairs area of the chic Eastern Suburbs home he shares with his wife, the interior designer Tamsin Johnson, and their two children. Johnson, 44, is dressed in a pair of green double-pleated pants, an Oxford shirt and a T-shirt, all of his own making; his left arm is adorned with a vintage Reverso watch that his wife bought him for his 30th birthday, a P.Johnson bracelet, two Cartier ‘Eternity’ rings and a customised signet ring on his pinkie, which used to have a smile emoji but now bears a turtle.

“I always try to make a little time for fun and inspiration when I travel, but it takes its toll. The upside is, you know, we get to live in Australia.” Home serves him well. Since hanging out his shingle in Brisbane in 2008, Johnson has invigorated the moribund Australian menswear scene with his modern take on perennially cool threads that nod to style heroes like designer Giorgio Armani and Gianni Agnelli, the Italian industrialist and cofounder of Fiat. (An enormous black and white image of the turned-out tycoon greets customers at the entrance to Johnson’s artfully appointed Paddington boutique in Sydney.) In addition to the original Brisbane store, he now has three locations in Sydney, with another three in Melbourne, and one each in London and New York. Then there are the regular trunk shows in Perth, Adelaide, Auckland, Jakarta, Kuala Lumpur, Los Angeles and Miami. When does he find the time to sew?

Not content with having become the go-to haberdasher for dapper gents—from the banking and legal set to more creative types who turn to him mostly for made-to-order pieces though he also sells ready-to-wear and accessories—he recently expanded into women’s wear. Just as with his men’s offerings, which avoid frippery in favour of stylish wardrobe staples that won’t scare the cat, his refined women’s ready-to-wear clothes are released in small capsule drops and eschew the built-in obsolescence of trend-driven labels.

“I am very conscious of waste in our business,” he says. “We try to operate in a way that we don’t contribute to landfill too much, and we don’t overproduce things. We used to wholesale, but it got out of hand, and I thought, hey, what are we doing here? We have a responsibility not to mindlessly feed the consumption cycle.”

Besides, he continues, the best part of his job is interacting with his clients to find out what is essential to them. “It sounds nerdy, but I love being a merchant and I love retail,” he gushes. “And by working with a client and being able to say, Hey, get that one for now, let’s think about that piece for next time, it allows us to grow with them and put the brakes on overconsumption.”

Unlike many fashion brands, it doesn’t sound like he is in a rush to expand his mini empire, even if a luxury conglomerate like LVMH or Kering comes knocking. “Look, never say never, and those companies have some impressive aspects to them,” he says. “You need some growth to stay alive, but I’ve got no interest in being the biggest. As naive as this sounds, I want to be the best retailer in the world. That’s really what I’m trying to do.” —HORACIO SILVA

MEXICO | Olivia Villanti

“Quiet Luxury” may be the catchphrase these days, but Olivia Villanti has been crafting her own timeless, high-quality, understated aesthetic since she founded her Mexico City–based womenswear label four years ago.

After transitioning from dance to a career in fashion—which included stints at a PR agency and the now-defunct Lucky magazine—Villanti began working as a copywriter for J. Crew during the Mickey Drexler days and later became the editorial director at its Madewell offshoot. In 2019, the Rhinebeck, N.Y., native relocated to Mexico City, where her husband is originally from; the couple planned on staying only a year, but then the pandemic hit.

Villanti found herself rummaging through her in-laws’ fabric and shirting studio, Gilly e Hijos, which her husband’s grandfather started after he emigrated from France. “He developed relationships with some really amazing mills,” she says. Now run by Villanti’s uncle-in-law, Bruno Gilly, the atelier specializes in bespoke men’s shirting using European textiles. “I was so charmed by the fact that you could walk into the offices of my in-laws as a male client and choose from eight different collars, inner linings, buttons, and cuffs,” Villanti says. “I don’t know many people that are offering this experience to women.”

In 2020, she started sampling patterns and designed a tunic-length tuxedo top that became the jumping-off point for her own made-to-order clothing line, which she named Chava Studio, using a Mexican slang term for a young woman. The online-only brand quickly gained an ardent following for its fresh take on shirting: a juxtaposition of traditional men’s tailoring with a decidedly feminine perspective that results in button-front styles with details such as cocktail cuffs, cutaway collars, and puffed sleeves. Swiss cotton is her go-to fabric, but she also uses silk and linen.

Villanti, 42, has no formal design training, yet she learned the ins and outs (say, how to properly fuse interlining to a collar) under Gilly’s tutelage. His team of four seamstresses help produce the clothes, along with Villanti’s two tailors.

Chava has seven styles in its core collection and drops 10 to 12 limited-edition pieces each season. The runs are often in short supply because, to reduce waste, Villanti relies primarily on deadstock materials the atelier has archived over the years. She buys a few fabrics directly off the line, among them the white twill for Chava’s tuxedo shirt. But others, such as fine Alumo cotton, must be sourced seasonally, and the amount she’s able to acquire dictates how many shirts can be cut. In addition to shirting, Chava offers tailored basics in both ready-to-wear and made-to-measure options, including trousers, blazers, and even hair accessories that salvage fabric scraps. Prices for the fall collection start at $395 for a shirt.

For made-to-order designs, clients can send Chava their measurements, do a virtual session with help from Villanti, or make an appointment at the Mexico City showroom; Villanti also occasionally holds trunk shows in New York City and Los Angeles. For now, her focus remains on markets in the U.S. and Mexico, and she has recently started looking at bigger facilities to increase Chava’s output. On average, the company now produces fewer than 20 items per week.

“I love the idea of us growing, and it’s scary, but I can see how many more opportunities it would give us to play and come up with new designs more frequently,” Villanti says. As for where she gets her inspiration, “I’m going to say something obnoxious: me.” —ABIGAIL MONTANEZ

INDIA | Vikram Goyal

After quitting his high-finance job in Hong Kong in 2000, Vikram Goyal returned to his native India—and found his calling. The Princeton-educated Delhi native, who’d also worked for the World Bank in the U.S., saw opportunities in his home country as it unshackled itself from longtime economic protectionism. Media and telecoms were booming… until they weren’t. “It was buzzing when I came back here, and then the sector just imploded,” the now-59-year-old recalls. “But, at the back of my mind, I’d always wanted to work with something indigenous.”

So he ditched his finance career and took a leap of faith, first venturing into an Ayurvedic beauty line called Kama Ayurveda (since sold to fashion and cosmetics giant Puig) and then a design studio in New Delhi. He had no formal training but had been immersed in Indian crafts since childhood, when he took regular trips to Rajasthan to visit his grandfather, an avid collector of Indian miniatures. Goyal wanted his new enterprise to pay tribute to both that tradition and the man who schooled him in it by showcasing the artistry of the country’s metalworkers. His connections (Goyal descends from Udaipur nobility) and unusual approach to materials—swapping in brass for the more typical gold, for example—earned him major commissions domestically.

He has since spent more than two decades building his business into a 200-person atelier catering to India’s elite. Now, Goyal is about to make a splashy debut stateside. He has just signed with Los Angeles–based design gallery FuturePerfect, which will spotlight his collection in a stand-alone booth at this year’s DesignMiami in December, while his collaboration with wallpaper specialists de Gournay, taking inspiration from the 16th-century Book of Dreams, housed in Rajasthan, arrives this month.

Goyal, who studied engineering, provides creative direction and business acumen, but as he considers himself neither an artist nor a designer, he leaves execution to the dozens of artisans he employs. The studio focuses squarely on metal, whether brutalist objects or welded, sculptural furniture. Still, it’s best known for expertise in hollow joinery and repoussé, the painstaking technique in which bas-relief-style images are pounded into a sheet of bronze.

“It’s all to do with control—over your hands, your breath—so you have to be very calm to get it right,” he explains. “It’s not like wood, chipping off, because applying pressure in one area will be at the expense of what’s beside it.” The method is also time-consuming; it might take a team of six workers 10 weeks to finish a single ornate piece. Goyal likens the ancient process to “drawing, but with metal.” No wonder prices for small panels start at $20,000 and can run to $350,000 for a 30-foot-long mural.

Goyal believes the key to his success lies in vertical integration. In India, most craftspeople of this ilk continue to be self-employed, which limits their efficiency and, therefore, their output. Goyal has instead assembled a staff that can handle every stage of product development. “We have designers, engineers, architects, and artisans working collectively, which means we’re able to take risks and push the envelope,” he says of their experimental work: The new wallpaper, for example, is an expression of repoussé-like imagery but in a different material. And that’s not the only distinction between his studio and a traditional workshop. “The bulk of my senior management and designers are women,” he notes, “and I intend to keep it that way.”

The studio’s shimmeringly decorative work is intended to evoke Indian culture while still adopting a modern, international design language. “You see a lot of metal in India—it’s part of everyday life from surface decoration to ritual vessels—but you also see a lot of brass and gold across the Art Deco buildings in Paris or New York,” Goyal explains. “You don’t see that so much in contemporary product design—it’s all just a grayish tone.” He pauses. “That will change.” —MARK ELLWOOD

CHINA | Qin Gan

China has come to dominate industrial watchmaking to such a degree that some collectors dispute out of hand that a Chinese watchmaker, without European training or Swiss-bestowed credentials, is even capable of producing a truly fine timepiece—say, one with mirror-grade chamfered edges that meet elegant Geneva stripes running all the way into tight corners. But Qin Gan, of Chong-qing, an enormous city in the country’s southwest, is creating watches that do precisely that.

Though Qin has crafted highly complicated models incorporating tourbillons, chiming mechanisms, and even automata, it’s his refined time-only designs—the Pastorale I, released in 2019, and especially the Pastorale II, recently revised in 18-karat white or rose gold and priced at $46,000—that have serious collectors adding their names to his three-year waiting list: Many enthusiasts consider time-only watches to be the purest expression of mechanical and aesthetic harmony, to say nothing of dress watches’ growing cachet.

Though he has seen the Pastorale II only in photographs, Paul Boutros, head of watches for the Americas at Philips, says he is “extremely impressed with the overall design, size, proportions, and finishing quality,” from the black-polished components to the champlevé enamel. “That he executes all of the finishing work himself without a support network in China makes the watch all the more impressive.”

Hong Kong–based financier James Li, who owns timepieces from F. P. Journe and other high-end independent makers, has been waiting for his Pastorale II for three years and tells Robb Report that when he finally saw the prototype sample, “I was blown away. The impression it gives me is very, very high-end—high horology. Every angle you look at it from, you can tell design details have been paid attention to.”

Qin, 55, grew up in a milieu familiar to many master horologists: His father ran a small watch and clock shop, and Qin remembers him working on European models such as Rolex, Omega, and Enicar. “This was in the 1970s, toward the end of the Cultural Revolution,” he recalls, noting that his father’s clients were “mostly the elite people of the society—company managers, army officials, and individual merchants.”

Though Qin studied art history and visual art, he always gravitated back to horology. “But it wasn’t until 2005 that I started making my own watches full-time,” he notes. “That’s when I really began practicing the polishing seriously.”

As Qin further studied the watchmaking process in books and on the internet, he came to realize that the local equipment available to him was not up to snuff—so he built his own. He retired most of those DIY tools a decade ago and purchased “some really top-tier, top-notch machines,” he says, “for instance, the Geneva-stripes machine and some other small, modern machines for polishing.” For cutting gears and pinions, he uses a Swiss gear-hobbing device, which sits behind him as we speak, its familiar industrial-beige paint job and exposed drive belts looking decidedly mid–20th century.

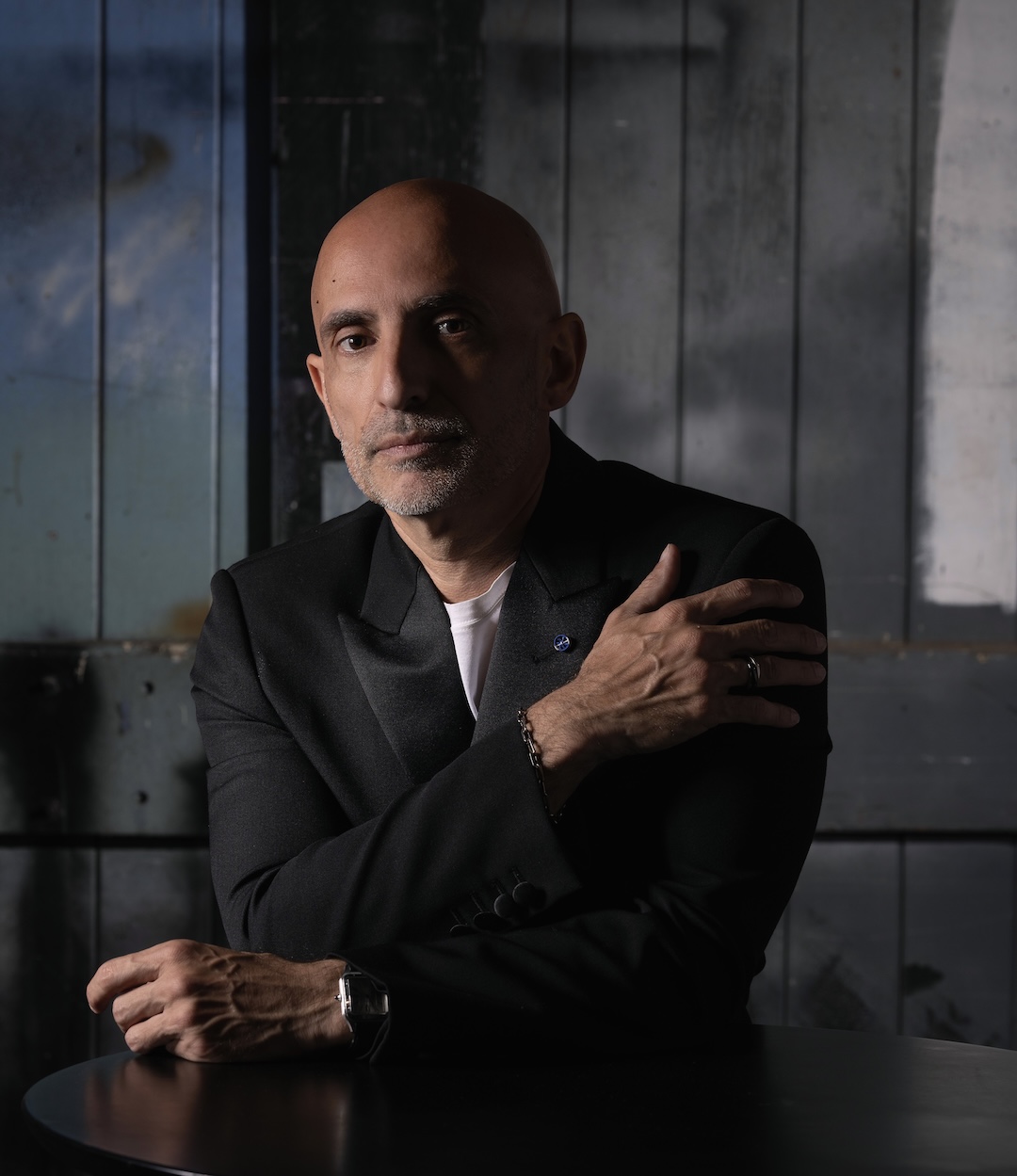

Riccardo Svelto

Qin fabricates the majority of the parts himself, but he imports the mainspring, hairspring, and shock-absorption system from Switzerland and Germany and sources cases from China before hand-finishing them; all told, he’s working in the same manner as most individual makers of high-end watches, wherever they’re based. As for the notion that such a beautifully crafted watch could not otherwise be made in China, chalk it up to a long-standing Eurocentric bias within the collector community.

His countrymen in that circle, Li says, “are so proud that finally there is a Chinese watchmaker who can make fine pieces at this level.” For Li himself, he adds, it was “hugely, hugely” important that Qin has emerged in China.

One day, Qin would like to return to building more complicated watches. For the foreseeable future, though, he can produce about 15 Pastorales a year, meaning his client base will remain small by necessity. But his renown faces no such constraint. “The kind of people inquiring about my watches have been collecting for a very long time, and they tend to have a mature aesthetic,” he says. “That’s what resonates with my work.” —ALLEN FARMELO

LEBANON | Joelle Kharrat

Coming of age in Beirut in the 1990s, Joelle Kharrat was surrounded by elaborate gold necklaces and stacks of bracelets. “In Lebanon, there is really a culture around jewellery,” she says. “My mom used to wear a lot of jewelry, like all Lebanese women, so it really influenced me and has always been there.” Nevertheless, her namesake collection doesn’t look anything like the ornate creations typically worn in the region. In fact, you might be hard-pressed to find her pieces in stores there. “I don’t even try too much in Beirut,” says Kharrat, 46, though she remains based in the capital and operates her business there. “I don’t think they can understand the concept, because it’s a very different way of wearing jewelry here.” Abroad, however, her sculptural totem necklaces have been capturing the attention of aficionados in the U.S. and Europe since their launch in 2022.

Kharrat’s breakout success isn’t entirely a surprise. Her fashion-jewelry label, Jojoba, which she ran for 10 years until 2018, was well-received internationally and sold at major global luxury e-tailers such as Net-a-Porter and MatchesFashion. But after a whirlwind of events—from the pandemic to a financial crisis in Beirut to her father’s death—she stopped working for two years. That time, however, proved to be fertile creative ground. “I kept on drawing and drawing, and I don’t know why, but I kept on working on this totem, because I’m very inspired by Saloua Raouda Choucair,” says Kharrat, referring to one of Lebanon’s most acclaimed modern artists. “She did these totems and compilations of elements, and I kept on doing the same thing. I think I was going through a phase, and I was really lost, so I needed something very strong.”

Emerging from a need for an artistic outlet during a time of loss, the totems became symbolic talismans of her own transformation. “I always loved fine jewelry,” she says, “so when my dad passed away, I said, ‘You know what? I’m going to do what I like.’ ”

The pendants are made by local craftspeople and are available either in solid 18-karat gold or a mix of the precious metal with everything from diamonds, mother-of-pearl, and pink opal to turquoise and wood. Each piece of the totems unscrews along a central spine so that owners can connect or remove elements. “I love when people call me after and ask, ‘Can I add a piece? Can I add diamonds?’ ” says Kharrat.

Her inventive formula quickly took off. The hip Parisian boutique By Marie was the first to embrace her designs (she jets to her apartment in that city about once a month), and her necklaces can now be found in a few select retailers around the globe, from Tiny Gods in Charlotte, N.C., to Aubade in Kuwait. Three more will soon carry the line in the U.S., and a major online retailer is expected to follow. For now, she’s sticking to her singular style, with plans to introduce earrings and a bangle. “I just want to do it the way I’m doing it nowadays because it makes me happy,” she says. “I don’t want to push it, and I don’t want to be everywhere.” —PAIGE REDDINGER

TURKEY | Ali Sayakci

By the age of 26, entrepreneur Ali Sayakci had already carved out a successful career exporting marble from his native Turkey. Less than a decade later, he decided to dive headfirst into the marine industry. The self-described ideas man, who studied abroad in the U.K. and had extensive family connections to yachting, attended a maritime conference in England in 2011 that inspired him to create a new type of explorer yacht.

“At the time, explorers were highly functional vessels but were rather ugly,” the 46-year-old tells Robb Report from his new 90-foot model in Bodrum. “My goal was to make one that was sexier, and slightly faster, than the others on the water. I thought we could use the curves of the new Range Rover.”

Sayakci enlisted Dutch studio Vripack to make his dream of a sleek SUV for the seas a reality. “They were—they still are—the best at designing expedition vessels,” he says. Senior designer Robin de Vries finished drafting the first iteration in 2013, and Sayakci began building the inaugural hull in 2016, wrapping construction in 2018. He christened the 85-footer Rock. The name was a nod to not only his marble enterprise but also his family’s roots in mining—his grandfather was one of the world’s biggest boron suppliers, he says—as well as the robust nature of the go-anywhere cruiser. Sayakci took Rock to the Cannes Yachting Festival the same year and sold it on the first day. The Swiss buyer wasn’t the only seafarer impressed with its debut: One industry publication called it “a revelation in the yachting sector.”

That success prompted Sayakci’s wife to propose he take over her late father’s company Evadne Yachts in 2020. He obliged but decided to ditch the sailing ships the Istanbul yard had been producing and start an entire Rock line.

In the niche field of explorers, much larger players were operating in Italy, the Netherlands, and Taiwan, not to mention other Turkish outfits that had entered the fray as well, but Sayakci believed he had pinpointed latent demand. “I thought, you know, there will be more need for explorers with a contemporary style,” he says.

As predicted, the explorer segment has grown exceedingly popular over the past few years, with more yards catering to owners looking to traverse the remotest corners of the globe in the lap of luxury. Sayakci believes his Rock vessels have an edge thanks to the design team’s “very Dutch approach” to maximizing square footage on the steel-hulled yachts and using computational fluid dynamics (CFD) to “solve the speed problem.”

Sayakci has also given the fleet his unique stamp while simultaneously putting his quarries to good use: Via a virtual tour of the new Rock 90 beach club, he points out the elegant marble furniture, plus some exterior metalwork inspired by his Audemars Piguet Royal Oak Offshore. The vessel, christened Rock X, with a base price of roughly $7.18 million, was set to be displayed at the Cannes and Monaco yacht shows in September—but he may decide not to part with it. “She was built on spec,” he says with a smile. “I can keep or sell.”

The Rock lineup currently counts five models, ranging from the original Rock 85 to the nearly 138-foot Big Rock 140. Evadne has transitioned from building yachts “one by one” to what Sayakci calls a “production-line model,” meaning it can start turning out standardized platforms at speed. The yard has delivered four hulls in the past six years, with two more currently under construction. High-profile clients include a film producer in Hong Kong and an influencer in China. Sayakci says he hasn’t yet landed a U.S. client because he keeps selling the yachts before they can be seen at the stateside shows—but he’s confident that American buyers will appreciate his designs. “I think the best market for us is the U.S.”

Objectively, Rock’s momentum is a major achievement in an industry that’s slow to change, but Sayakci says that entrepreneurs like him seldom feel successful because they are “always looking forward.” To wit, he has just launched a new water brand. It surely won’t be his last big idea. —RACHEL CORMACK

Subscribe to the Newsletter

Recommended for you

Vacheron Constantin Just Unveiled Its Traditionnelle Perpetual Calendar Ultra-Thin Without Diamonds

The trio of 36.5 mm watches is available in white or pink gold.

By Carol Besler

December 9, 2025

Billionaires Now Hold a Record $23.7 Trillion of the World’s Wealth, a New Report Says

Over 190 people joined the billionaire club around the world in 2025.

By Nicole Hoey

December 9, 2025

You may also like.

You may also like.

Radek Sali’s Wellspring of Youth

The wellness entrepreneur on why longevity isn’t a luxury—yet—and how the science of living well became Australia’s next great export.

Australian wellness pioneer Radek Sali is bringing his bold vision for longevity and human performance to the Gold Coast this weekend with Wanderlust Wellspring—a two-day summit running 25-26 October 2025 at the RACV Royal Pines Resort in Benowa. Sali, former CEO of Swisse and now co-founder of the event and investment firm Light Warrior, has long been at the intersection of wellness, business and conscious purpose.

Wellspring promises a packed agenda of global thought leaders in biohacking and longevity, including Sydney-born Harvard researcher David Sinclair, resilience pioneer Wim Hof, performance innovator Dave Asprey and muscle-health expert Gabrielle Lyon. From immersive workshops to diagnostics, tech showcases, and movement classes, Sali aims to make longevity less a niche pursuit for the elite and more an accessible cultural shift for all. Robb Report ANZ recently interviewed him for our Longevity feature. Here is an edited version of the conversation.

You’ve helped bring Wellspring to life at a moment when longevity seems to be dominating the cultural conversation. What drew you personally to this space?

I’ve always been passionate about wellness, and the language and refinement around how we achieve it are improving every day. Twenty years ago, when I was CEO of Swisse, a conference like this wouldn’t have had traction. Today, people’s interest in health and their thirst for knowledge continue to expand. What excites me is that wellness has moved into the realm of entertainment—people want to feel better, and that’s something I’ve always been happy to deliver.

There are wellness retreats, biohacking clinics, medical conferences everywhere. What makes Wellspring different?

Accessibility. A wellness retreat can be exclusive, but Wellspring democratises the experience. Tickets start at just $79, with options up to $1,800 for a platinum weekend pass. That means anyone can learn from the latest thought leaders. Too often in this space, barriers are put up that limit who can benefit from the science of biohacking. We want Wellspring to be for everyone.

You’re not just an organiser, but also an investor and participant in this field. How do you reconcile passion with commercial opportunity?

Any investment I make has to have purpose. Helping people optimise their health has driven me for two decades. It’s satisfying not just as an investor but as an operator—it builds wonderful culture within organisations and makes a real difference to people’s lives. That’s the natural fit for me, and something I want to keep refining.

What signals do you look for in longevity ventures to separate lasting impact from passing fads?

A lot of what we’re seeing now are actually old ideas resurfacing, supported by deeper scientific research. My father was one of the first in conventional medicine to talk about diet causing disease and meditation supporting mental health back in the 1970s. He was dismissed at first, but decades later, his work was validated. That experience taught me to look for evidence-based practices that endure. Today, we’re at a point where great scientists and doctors can headline events like Wellspring—that’s a huge cultural shift.

Longevity now carries a certain cultural cachet—its own insider language and status markers. How important is that to moving the field forward?

Health is our most precious asset, and people have always boasted about their routines—whether it’s going to the gym, doing a detox, or training for a marathon. What’s different now is that longevity practices are gaining mainstream recognition. I see it as something to be proud of, and I want to democratise access so everyone can ride the biohacking wave.

But some argue that for the ultra-wealthy, peak health has become a kind of luxury asset—like a private jet or a competitive edge.

That’s short-sighted. Yes, there are extremes, but most biohacking methods are accessible and inexpensive. Look at the blue zones—their lifestyle practices aren’t costly, yet they lead to long, healthy lives. That’s essential knowledge we should be sharing widely, and Wellspring is designed to do that in an engaging way.

Community is often cited as a key factor in healthspan. How does Wellspring foster that?

Community is at the heart of it. Just as Okinawa thrives on social connection, we want Wellspring to be a regular gathering place where people uplift each other. Ideally, it would become as busy as a Live Nation schedule—but for health and wellness.

Do you worry longevity could deepen class divides?

Class divides exist, and health isn’t immune. But in Australia, we’re fortunate—democracy and a strong equalisation process help maintain quality of life for most. Proactive healthcare, like supplementation and lifestyle changes, isn’t expensive. In fact, it’s cheaper than a daily coffee. That’s why we’re one of the top five longest-living nations. The opportunity is to keep improving by making proactive health accessible to everyone.

Some longevity ventures are described as “hedge-fund moonshots.” Others, like Wellspring, seem grounded in time-tested approaches. Where do you stand?

There’s value in both, but I’m more interested in sensible, sustainable practices. Things like exercise, meditation, and community-driven activities are proven to extend life and improve wellbeing. Technology can support this, but we can’t lose sight of the human elements—connection, balance, and purpose.

Finally, what role can Australia—and Wellspring—play in shaping the global longevity conversation?

The fact that we can put on an event like Wellspring, attract world-leading talent, and already have commitments for future years says a lot. Australia is far away, but that hasn’t stopped great scientists and thinkers from coming. We’ll be here every year, contributing to the global conversation and, hopefully, helping more people extend their healthspan.

You may also like.

30/09/2025

‘Continuum’ Opens to Rave Applause at Sydney Dance Company

Rafael Bonachela’s latest curatorial triumph premiered last night at the Roslyn Packer Theatre, dazzling audiences with its emotional range and fearless physicality.

Sydney Dance Company opened its latest season with Continuum, a triple bill that reminds audiences why the ensemble remains Australia’s most compelling cultural export. Receiving a standing ovation at its premiere last night at the Roslyn Packer Theatre, the program unfolds as an elegant meditation on movement and metamorphosis—three distinct choreographic visions held together by Rafael Bonachela’s curatorial precision and instinct for contrast.

Stephen Page’s Unungkati Yantatja – one with the other breathes land, sea, and sky into motion; Tra Mi Dinh’s Somewhere between ten and fourteen lingers in the tender light between day and night; and Bonachela’s own world-premiere Spell delivers the evening’s visceral heartbeat. Together they trace the continuum of life itself—fluid, volatile, and impossible to pin down. Running through 1 November, the production affirms Bonachela’s vision of dance as “an ever-evolving conversation between artists, audiences, and the world around them.” Robb Report ANZ recently caught up with Bonachela.

Continuum is described as “a bold exploration of the ever-shifting cadence that binds us to the world.” How did this idea of constant transformation influence your choreographic choices in Continuum?

I’ve curated this evening as an invitation for audiences to experience dance as an ever-evolving conversation—between past and present, between the individual and the collective, and between diverse artistic voices. My intention with this program is to spark connection, curiosity, and reflection, offering works that challenge, move, and inspire while revealing the transformative power of the body in motion.

Each choreographer brings a distinct perspective, yet all share a commitment to exploring the body in motion as a vessel for transformation. Through contrasting aesthetics, cultural resonances, and shifts in time, these works reveal how dance exists on a continuum—where moments build upon one another, find new meanings in fresh contexts, and affirm the enduring power of the human form to express what words cannot.

You’ve created the world premiere Spell within Continuum, which explores “the limits of emotional and physical expression.” What did you aim to conjure emotionally and physically through Spell, and how does it dialogue with the other works in the triple bill?

The title Spell itself suggests a duality—it can be something magical, but also something we fall under without even realising. Emotionally, I want to evoke an atmosphere that is at once intimate and volatile, where vulnerability and power exist side by side. There’s a ritualistic quality to the work, as if the dancers are caught inside a force they cannot quite escape—and it’s that tension which drives the movement and fuels the piece.

Within Continuum, Spell emerges as an intense, visceral heart—both contrasting with and speaking to the other works. While it shares the evening’s theme of transformation, it explores it through a lens of emotional ignition and fearless physicality.

In crafting Continuum, how did you balance moments of intimacy and expansiveness—especially when layering live elements like music and immersive lighting—to evoke that ebb and flow of life’s narratives?

In Continuum, each choreographer works with complete artistic freedom, without any direction from me. That independence brings out authentic contrasts and unexpected connections between the works. It’s this variety that invites audiences to engage on their own terms, discovering personal meanings and emotional threads that are unique to each viewer.

This triple bill seems to offer a journey through time and place—from twilight’s fleeting beauty to elemental breath. How do you want audiences to experience—and perhaps rethink—the relationship between movement, nature, and storytelling?

I always want audiences to come with an open mind and allow the experience to be unprescribed free to discover their own meanings and narratives. Dance has the unique power to be felt as much as it is seen, to resonate physically and emotionally in ways words can’t. I hope audiences leave with a renewed sense of how deeply movement is connected to the natural world, and how it can tell stories without language. Like nature, this evening is always in motion—emerging, transforming, and fading—so that each work becomes a landscape the audience can journey through, sensing their own place in the continuum of life

Looking ahead, does Continuum carve out a new direction or personal milestone for your artistic trajectory? What might this signal for your future choreographic explorations?

Continuum feels like both a culmination and a starting point. It gathers threads from my past work, my fascination with transformation, my love of collaboration, my search for emotional truth and weaves them into something that opens new doors.

Creating and curating this triple bill has changed how I see works interacting—how contrasting voices can strengthen shared themes. It’s inspired me to explore even more fluid boundaries between ideas, styles, and disciplines.

If it signals anything for the future, it’s that I’m interested in going further into that space where dance is not just movement, but an ongoing conversation—between artists, between forms, and between audiences and the world around them.

Continuum runs through November 1 at the Roslyn Packer Theatre.

You may also like.

Inside the $30 Billion Obsession Among the Ultra-Wealthy : A Race to Live Longer

The pursuit of an extended life has become a new asset class for those who already own the jets, the vineyards, and the art collections. The only precious resource left to conquer, it seems, is time.

If you want to know what the latest obsession is these days among the ultra-wealthy, listen in at dinner.

Once it was crypto, then came AI and psychedelics, now it’s longevity all the time. The talk is of biomarkers, NAD+ levels, and methylation clocks, of senolytics and stem cells. Guests compare blood panels like wine lists, and the most important name to drop is no longer your banker or contact at Rolex but your longevity physician. For those just arriving at the conversation, the new science can sound like science fiction—but it’s fast becoming the lingua franca of money.

The field has its own vocabulary—epigenetic reprogramming, which aims to reset cellular clocks; cellular senescence clearance, the removal of “zombie” cells that clog our systems as we age; precision gene therapies, designed to personalise interventions at the level of DNA—that sounds equal parts Brave New World and Wall Street pitch deck. But make no mistake: this is no longer a niche pursuit. The sector is already worth an estimated $30 billion globally and projected to surpass $120 billion within the decade, having attracted billions in investment from the likes of Altos Labs, Juvenescence and Google-backed Calico. Tech titans and old-money families alike are staking claims on the possibility of an extra decade or two. It’s a space where venture funds court Nobel laureates, hedge funds bankroll gene-therapy moonshots, and even wellness festivals in Australia draw rock-star scientists to the stage.

The Poster Child and the Pitch

David Sinclair, the Sydney-born Harvard geneticist who has become something of a poster child for the field, is quick to underline the stakes. “We’re not just talking about lifespan, we’re talking about health span,” he tells Robb Report. “Extending the number of years people live well—without frailty, without disease—isn’t just a medical breakthrough. It’s a social and economic one.” Sinclair, whose research ranges from NAD boosters to epigenetic age-reversal therapies, has calculated that adding a single year of healthy life to the US population, for example, could be worth $38 trillion in economic benefit—fewer years of costly aged care, less burden on hospitals, more years of productivity and compounding returns. In other words, the dividends of health are financial as well as personal. “That’s why governments and investors are paying attention,” he says.

Sinclair has become a fixture on the global circuit, drawing crowds that rival TED or Davos. As Radek Sali, the Australian entrepreneur behind the new Wanderlust Wellspring longevity festival taking place on the Gold Coast this October, where Sinclair is the keynote speaker, puts it: “Wellness has moved into the realm of entertainment.” At Wellspring, platinum-tier guests pay up to nearly $2,000 for the privilege of hearing scientists and investors share the stage over a weekend like headliners at Coachella.

Investing in Time

And then there are the sideshows. Bryan Johnson, the tech mogul turned human guinea pig, makes headlines with his open-source, organ-by-organ data tracking—his infamous “penis readings” have become cocktail-party fodder. While many dismiss him as a parody of the field, his multimillion-dollar project Blueprint has nevertheless made longevity impossible to ignore in the mainstream.

For the uninitiated, the science of longevity today is no longer about vitamin salesmen or fringe dietary regimes. This is the new frontier—one where biology is not just observed but engineered, and where investors smell opportunity on par with space travel. It’s little wonder that Altos Labs has raised billions to chase cellular rejuvenation, or that Juvenescence has secured more than $400 million to fast-track therapies. What was once the realm of eccentric tinkerers now attracts sovereign wealth funds.

“This body takes me to meetings, earns me money—why not invest time and money into it?”

The appeal to the One Percent is obvious. Longevity is a natural extension of portfolio thinking: diversify your assets, hedge your risks, and above all, maximise return on investment. Except in this case, the returns are measured in years of health, energy and cognition. As Andrew Banks, a Sydney-based entrepreneur and early investor in Juvenescence, explains: “This body takes me to meetings, earns me money—why not invest time and money into it?” His Point Piper home teems with contraptions—a Reoxy breathing machine, hydrogen therapy, red-light sauna, and he spends a few hours a day on maintenance, as if his body were a private equity stake.

Banks, like others in his cohort, is baffled that more wealthy men haven’t followed suit. “Entrepreneurs pride themselves on divergent thinking,” he says. “They expand, dream and create businesses with it. But when it comes to their bodies, they’re convergent—unimaginative. The lack of curiosity is astonishing to me.”

Medicine 3.0 and the New Rituals

Steve Grace, a Sydney-based entrepreneur and the proprietor of exclusive private networking club The Pillars, which is opening a longevity program, thinks there is a reckoning coming for those who do not take matters into their own hands. “As someone who has run a few recruitment businesses,” he says, “I can tell you that if you’re a man or woman in your 50s and working as an employee, even in a really good position, it’s time to get worried about job security and being aged out of the workforce. You have to make yourself as vital as possible and become the best version of yourself, or you’re toast.”

What was once fringe has now become a cultural necessity for those who can afford anything, with science finally catching up to ambition. Sinclair’s lab at Harvard recently published a study on the reversibility of cellular ageing—restoring vision in blind mice and setting the stage for human trials in conditions like glaucoma. In Boston, his company Life Biosciences will begin treating patients with blindness in a Phase I trial using partial cellular reprogramming early next year. “This isn’t science fiction anymore,” Sinclair says. “We’re at the point where we can reprogram cells, turn back their biological clocks, and restore function.”

Meanwhile, practitioners like Dr. Adam Brown of the Longevity Institute in the Sydney suburb of Double Bay are reinventing diagnostics. His “assessment menu” has been compared—only half-jokingly—to a Michelin Guide for medical testing: full-body MRI scans, continuous glucose monitors, polygenic risk scores. “What we do is proactive, not reactive,” he says. “Correct deficiencies first, then optimise health. That’s how you get peak performance in the short term and resilience in the long term.” Brown frames longevity in terms that would resonate with any investor: “There’s a short-term ROI—fixing glucose or sleep issues so you perform better tomorrow. And there’s a long-term ROI—functioning in your 70s as you would in your 40s. That’s extending your career, your income potential and your independence.”

“Once upon a time, male vanity meant injectables, veneers and a tan. Today, it’s VO2 max scores and continuous glucose monitor readouts.”

Peter Attia, the Canadian-American physician and podcast host who has helped popularise the concept of “Medicine 3.0”, echoes this emphasis. Medicine 1.0, according to him, was about surviving infections. Medicine 2.0 was about treating chronic disease. Medicine 3.0 is about staying ahead of decline: measuring, monitoring and intervening early. “The goal is not just to avoid disease but to lengthen health span,” Attia has said.

For those already converted, longevity is less about lab science than daily rituals. Sydney-based Chief Brabon, who trains CEOs like athletes, says: “These men are like Formula One cars—you don’t wait until the tyres are bald before swapping them. You keep everything tuned, precise, optimised.”

That tuning now involves more gadgets than ever: hyperbaric oxygen chambers, cryotherapy, sauna/cold-plunge circuits, peptide stacks, nootropics. And yes, a glut of supplements, some with evidence, others little more than wishful thinking. Once upon a time, male vanity meant injectables, veneers and a tan. Today, it’s VO2 max scores and continuous glucose monitor readouts. “Health is the new flex,” as Steve Grace quipped, glancing at his wrist-worn biometric tracker.

The New Flex: Health as the Ultimate Luxury

Still, there is plenty of scepticism. Some therapies are unproven, others prohibitively expensive. And there is the unavoidable fact that many leading scientists, including Sinclair, have stakes in companies producing supplements and therapeutics, raising eyebrows about conflicts of interest. “The difference,” Sinclair insists, “is whether it’s backed by peer-reviewed science and measurable biomarkers. If it can’t be quantified, it’s marketing, not medicine.”

Then there are the contradictions. It promises democratisation while often priced like a private club. It champions science but thrives on hype. It seeks to extend health span but risks deepening class divides. “Only if we let it,” Sinclair says when asked if longevity risks becoming the preserve of the wealthy. “Like antibiotics or aspirin, these advances should become widely available and affordable once they scale.” Sali agrees, but from another angle: “Biohacking doesn’t have to be expensive,” he says. “The blue zones prove that—community, diet, movement, purpose. Those are free. Wellspring is about making that knowledge accessible.”

And yet, for all its shortcomings, the movement is here to stay. Investment continues to pour in. Technology—like senolytic drugs that clear aged cells or AI-driven platforms that predict individual disease risk years in advance—is moving from speculation to clinical trial. Scientists are being recast as influencers. And the wealthy, always in search of the next advantage, have found in longevity a pursuit as old as alchemy, yet dressed in the language of venture capital. The truth is that health has always been an asset. What’s new is that it’s now being traded, optimised and measured like one.

In the end, longevity is less about a moonshot than about curiosity. Banks, Sali, Sinclair, Attia are all, in their own way, betting on time. Perhaps the most radical idea is also the simplest: that the best-performing asset in any portfolio is the body itself. Unlike Bitcoin, it carries you to meetings. Unlike art, it cannot be stored in a vault. Unlike real estate, it is non-transferable.

The new calculus of longevity is the recognition that the ultimate luxury is not wealth or status, but a few more decades of clear thought, strong bones and good company—and the ability to make money off it. Everything else, as one investor put it, is just a rounding error.

You may also like.

How Sailing Shaped Loro Piana’s Most Iconic Designs

Pier Luigi Loro Piana grew his family textile business into a celebrated fashion house by following his passion for sports on land and at sea.

The Regatta Connection

The race village at Port de Saint-Tropez is awash with people in nautical navy and white, the de facto dress code for the Loro Piana Giraglia regatta. This is the second year the fashion house has lent its name to one of the Mediterranean’s most prestigious summer races. The course zooms from the French coast to Genoa, Italy, taking a sharp turn past Giraglia, a small island off Corsica’s northern tip. It’s the latest in a long line of marine events the brand has sponsored, dating back more than 20 years.

The link between sailing and the brand—and more consequentially the Loro Piana family—is exemplified by the man Robb Report is here to meet: Pier Luigi Loro Piana. An avuncular figure in his 70s with the physique of a man who has enjoyed life, Pier Luigi fell in love with sailing in his late teens, when a family friend took him for a cruise in a sloop.

“Using the wind to go faster or slower, driving the boat like it has an engine, it’s really fascinating,” he says. Inevitably, he started competing. “When you’re sailing, you’re always looking for other boats to go and fight with. It’s an instinct,” he says. And then, with considerable understatement, “I think it’s a nice hobby.”

A Life Under Sail

He currently owns two boats: My Song, which you can see on these pages, is a 25 m sailing yacht that competed in the Regatta. There’s also Masquenada, a comfortable 50 m explorer. It’s a commendable set-up befitting a man who shaped one of Europe’s most celebrated fashion houses.

A Family Business Turned Global Powerhouse

The textile and clothing company that bears his family’s name was launched by an ancestor, Pietro Loro Piana, in 1924. A few generations later, Pier Luigi and his brother, Sergio, would run it for four decades until LVMH acquired a majority stake for around $4 billion in 2013. Sergio passed away that year; his widow and Pier Luigi still own a share of the brand between them.

The brothers proved innovative custodians, moving the company upmarket with an insistence on ultra-fine materials and groundbreaking fabrications. And the connection with sports—specifically yachting, horseback riding, skiing and golf—is integral to how the brand positions itself. As Pier Luigi recalls, such associations often had self-serving origins.

“These are the sports my brother and myself were doing,” he says. “We were very committed in business in the 1970s, ’80s, ’90s, so we were like our customers: people that like to work hard but also play hard. And that meant sports.”

Innovation Born of Necessity

This affinity often led them to develop durable, yet elegant, materials and gear for their off-duty pursuits, eventually offering versions to their athletic clientele. “We engineered products with unusual properties, natural fibres like wool or cashmere with a membrane that makes it waterproof and windproof… For research and development, I was the first victim,” he says with a chuckle. Once, he wanted a ski jacket that was “warmer, lighter, softer and better” than nylon models, so he made a prototype to test on the slopes. It gave birth to the Loro Piana Storm System, launched in 1994. The line’s wind-resistant waterproof wool and cashmere has since been used by brands around the world. “I still have this jacket,” he says.

The same process happened on the water. A beloved reversible bomber, with knitted cashmere on one side and waterproof polyester on the other, was born from Pier Luigi’s need for a functional jacket to wear on his yacht. “It’s very light, doesn’t wrinkle, it’s warm, windproof,” he says. “It solves so many problems.”

He takes less credit for perhaps the brand’s most famous—and almost certainly most imitated—product, the white-soled suede Summer Walk loafers. “That was my brother,” he says. “When we were 20, 30 years old, we went sailing and there were only [Sperry] Top-Siders or Sebagos. But when the soles got worn, they got hard and slippery.”

The answer: a non-marking sole with grip—“like a tire you use in Formula 1 when it’s wet”—which Sergio got his bespoke shoemaker to sew to suede uppers. Eventually, they produced two versions: a loafer and the Open Walk, a model with a slightly higher top. “We discovered people were using them also for formal wear because they were so comfortable,” says Pier Luigi. “It’s really a successful story that started from product research.”

And if problem-solving can turn your family business into a giant of global style, clearly it pays to be a little selfish.

You may also like.

The Supercar of Pool Tables

In a rare fusion of Italian design pedigree and artisanal craftsmanship, Pininfarina and Brandt have reframed the barroom game as aerodynamic high art.

In the rarefied realm where leisure meets design, the latest object of desire doesn’t purr down the autostrada—it commands the room from a single sculptural base. The Vici pool table, a collaboration between Italian automotive legend Pininfarina and Miami’s bespoke table-maker Brandt Design Studio, reimagines the game with the same aerodynamic poise and artisanal precision that have graced some of the world’s most beautiful vehicles.

Named for Julius Caesar’s immortal boast—“Veni, vidi, vici”—this limited-edition series transforms billiards from casual diversion into a declaration of style. Every curve is deliberate, from the ultra-thin playing surface clad in tournament-grade Simonis cloth to the seamless integration of Italian nubuck leather and precision-milled metals. The effect is more haute sculpture than barroom pastime—yet it meets exacting professional standards.

For the true connoisseur, the debut PF 95 Anniversario edition celebrates Pininfarina’s 95-year legacy in just 95 numbered pieces. Finished in dark-blue lacquer with rose-gold accents and a flash of red felt, each table is discreetly nameplated—a tangible claim to an heirloom in the making.

“It’s not just about how it plays—it’s about how it lives in a space,” says Dan Brandt, the master craftsman whose work has long graced the world’s most exclusive interiors. Whether anchoring a penthouse salon, a members’ lounge or the main deck of a superyacht, the Vici is designed to stir conversation before the first break.

For those accustomed to Pininfarina’s sleek automotive silhouettes, this is a chance to bring that same lineage of movement, form and Italian refinement into the home. Only now, the horsepower is measured not in engines—but in the geometry of a perfect shot.

From pool to midcentury to Ottoman, we’ve got all the table angles covered at Robb Report Australia & New Zealand —plus more home-worthy pieces.

You may also like.

By Brad Nash

18/08/2025