Pay Dirt

In the highly scrutinised realm of philanthropy, organisations are turning to an aggressive class of research firms to ensure donations are scandal-free.

Related articles

For decades, the Sackler family bestowed tens of millions of dollars on hallowed universities and museums in the United States, the UK, Europe and Asia. Their philanthropy extended to Harvard, Yale, Princeton, Peking University, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Guggenheim Museum, the American Museum of Natural History, the Louvre, the British Museum, the Tate, the Victoria and Albert Museum and the Serpentine, to name a few.

As recognition for the billionaire pharmaceutical clan’s largesse, their name was plastered on galleries, wings and rooms housing valuable artworks and artifacts—until, that is, information about the source of one branch’s wealth came to light: they owned and operated Purdue Pharma, maker of Oxycontin, the highly addictive supernova painkiller regarded as the kick-starter of the opioid crisis, which has claimed the lives of almost a million people in the US.

When the media caught wind of the connection, activists erupted, appalled that sites of art, culture and higher learning would take what they considered to be blood money. Most memorable were the demonstrations led by artist Nan Goldin, where pill bottles were strewn down the iconic spiral ramp of the Guggenheim and prescription slips littered the floor of the Sackler Wing at the Met, home of the ancient Egyptian Temple of Dendur. As pressure mounted, these prestigious institutions were forced to address the tainted funds. The Louvre caved first, removing the dynasty’s name from the Sackler Wing of Oriental Antiquities. Soon after, the V&A, the Met, the Guggenheim and others followed suit.

The very public renunciation sent shock waves through the world of philanthropy, and both donors and institutions reeled. Though benefactor scandals were not unheard of, there’d never been a reckoning quite like this one. In the past, it had been easy for museums, universities and other nonprofits to turn a blind eye to the origins of their funding. The prevailing mindset was: if the cause was worthy, did it really matter where the money came from? But attitudes were changing, and respected institutions suddenly faced unprecedented scrutiny and challenges to their fundraising practices, as scandal after scandal made headlines: Jeffrey Epstein, Harvey Weinstein, Varsity Blues, Sam Bankman-Fried, Bill Cosby and even fallen cycling hero Lance Armstrong, who sat on the board of the Aspen Art Museum. Suddenly, trustees needed to concern themselves with not only the size of a donor’s check but also whether the signature on it would end up sullying the institution’s name.

Enter a new class of due-diligence companies. Though prospect vetting has been part of fundraisers’ duties for a while, investigating people willing to give an organisation money has never been so comprehensive. It’s typically those signing the checks who’ve enlisted consultants to tell them exactly where, how and by whom their hard-earned cash should be spent. Now, these firms are flipping the script by assisting museums, universities and other nonprofits in putting donors under a microscope, trawling their pasts for everything from criminal connections to money laundering to legal compliance—and even grey areas such as political associations and distasteful, if legitimate, business interests.

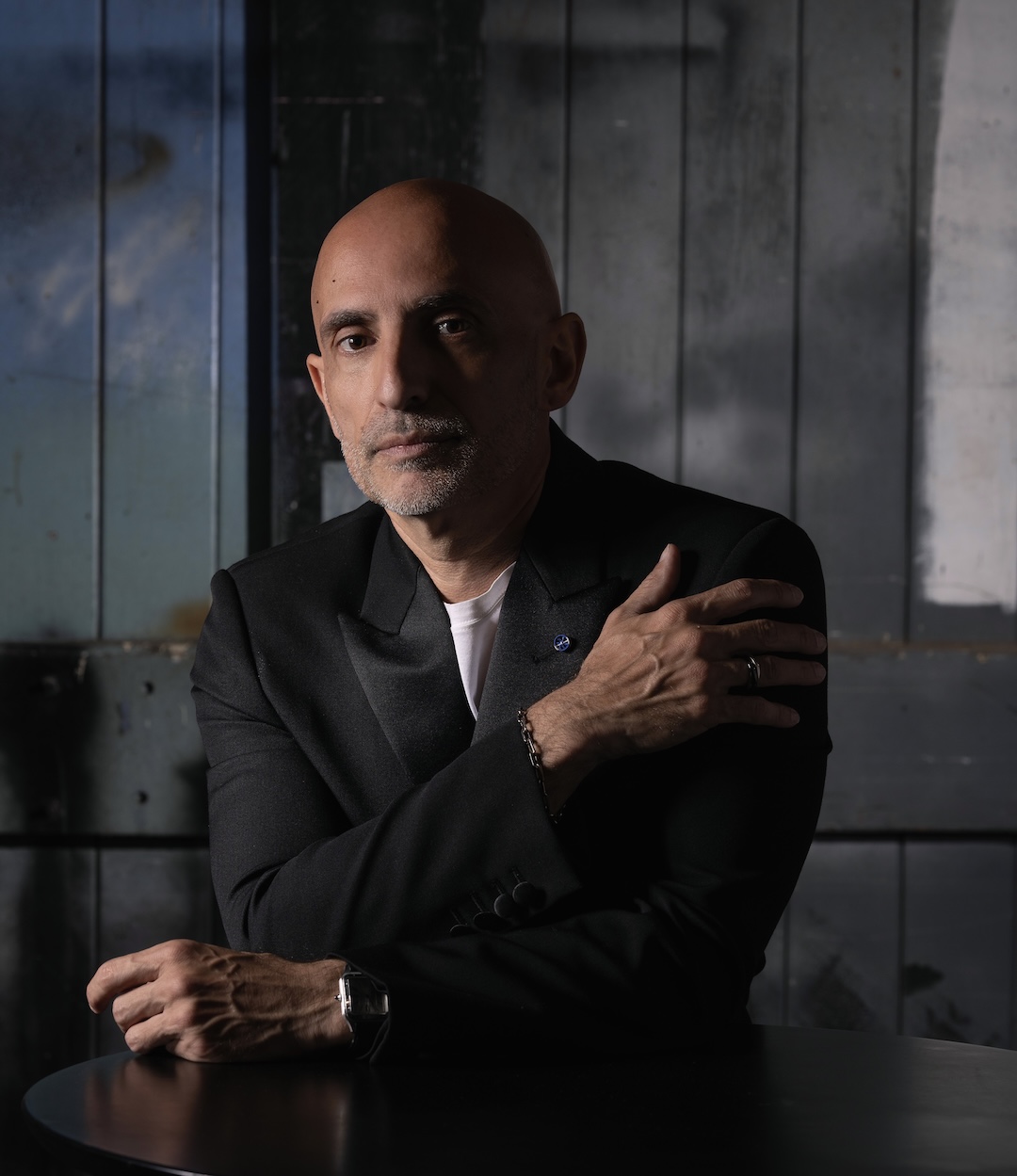

When Dan Secretan launched Xapien back in 2018, he thought its primary focus would be in financial services thanks to his background in financial crime, including anti-money laundering, know-your-customer, and transaction monitoring. Having worked with banks that frequently dug into their clients’ histories, Secretan knew there was a need. But after doing some market tests and speaking to a friend—the head of due diligence at Cambridge University, who recognised a gap—he quickly saw the potential to apply his expertise to the philanthropy sector. Xapien, which uses an AI tool that gathers background research on individuals, can provide valuable data in a matter of minutes. It’s based on large-scale investigation platforms for law enforcement, which one of Secretan’s partners, Shaun O’Mahony, had been building. “They’ve been using open-source intelligence to understand people for many years,” says Secretan, who took a bet on this branch of AI when it was in its infancy.

In the past, prospect research was a laborious task that required scouring libraries and public records. As the internet grew, information became more available, bringing with it an enormous bank of data. But for many, vetting the source behind each and every donation just wasn’t financially feasible; while anyone can do a Google search, it can be both limiting and overwhelming. “The information is out there, but it’s very hard to find it, distill it and make use out of it,” says Secretan. “We wanted to take all the research and knowledge but apply it with a commercial lens to organisations, charities and universities—because everybody needs to know who their third parties are.” Today, Xapien’s clients include the University of Pennsylvania, Tufts University, the University of Michigan, and, in the UK, King’s College London and the University of Manchester.

Penn—the colloquial name for the University of Pennsylvania—began using Xapien in 2023 after hearing about it from another university. Kathleen Martino, a senior prospect analyst at the Ivy League school, says that although the technology isn’t foolproof—it does better with Western-sounding names, for example, than Asian or Arabic ones—Xapien has made her research both faster and more thorough. She describes it as a one-stop shop.

“The wonderful thing about Xapien is it’s doing a function that we used to have to do step-by-step,” she explains. Rather than searching everything separately—lists of sanctioned individuals, criminal records, the subject’s charitable foundations and such—Martino can pull together a comprehensive report with Xapien, which she then hands off to a development officer. At that point, if there are red flags, “there is actually a committee process that senior leadership and potentially even legal get involved in where it will be discussed as to what is the reputational risk to the university.” Take into account that Penn does such checks not only on donors but also on nominees for boards, adviserships, and the like, and it becomes apparent what a heavy lift it can be.

“If a university says, ‘We are going to look at everyone we partner or work with,’ it takes a lot of work,” says David Garcia, director of non-profits at Altrata, parent company of Wealth-X, which services nonprofits and commercial businesses alike. “We’ll outsource it for you,” he says, adding that instead of AI, the data is mined by a comprehensive team of researchers.

Wealth-X launched 14 years ago with three people out of a WeWork; it now has some four million profiles of wealthy individuals in its database. During Garcia’s decade-long stint advising companies, he claims to have helped avert countless PR nightmares. He remembers taking meetings with clients in Washington, DC, who were intent on naming Elizabeth Holmes from Theranos to their board of directors. The fraud scandal that sent her to prison had yet to break, but Garcia’s team had already raised red flags as doubts about the tech had emerged. “There was a certain period where everyone in DC was saying, ‘We want to have her on the board’,” says Garcia. “She [had been] on the cover of all these magazines, she was a viral person, so everyone wanted to get in on that. They’re the flavour of the month,” he adds, but “when you look a little deeper, it gets murky.”

Garcia was able to advise his clients against engaging with Holmes. Others weren’t so savvy: the Harvard Medical School Board of Fellows reportedly rushed through its nominating process to offer her a seat. The morning of her first board meeting, The Wall Street Journal’s exposé of Theranos’s business practices broke.

Ironically, on the same trip when Garcia helped the clients dodge the Holmes bullet, he saw someone removing a Sackler plaque from a building. “Ten years ago, you could accept a gift from a shady person and you could turn a blind eye,” he says. “There wasn’t [a lot of ] activism.”

Beyond reputational harm, dabbling with unsavoury donors can mean losing out on future funding. “If you’re associated with someone who is controversial or has legal issues, which is happening so much more today, your big donors could stop donating,” Garcia says. Or, maybe worse, “your other donors could push back, and your leadership could come under pressure from the press.”

After Florida A&M University prematurely publicised a mammoth US$237.75 million (around $378 million) donation—the largest in any HBCU’s history—and it subsequently failed to materialise, the university president resigned under a cloud, as did the vice president for advancement. A third-party investigation found that staff felt pressured to ignore red flags. Eager for the game-changing gift, the president Larry Robinson is said to have told them “not to mess this up”. The report didn’t mince words about the allegedly less-than-altruistic motives of the donor, a hemp farmer named Gregory Gerami who’d previously withdrawn an eight-figure pledge to another school: being associated with an institution of higher learning conveys a sheen of trustworthiness and credibility.

There’s also the issue of money spent making the scandal go away. “That’s where I think the due diligence of looking into who your donors are is also important,” says Austin Vogt, prospect researcher for Mercy for Animals, a Xapien client. Crisis-management PR can create a huge financial strain on organisations. “You may be accepting money, but then you would have to spend money after the fact,” says Vogt.

Garcia has seen many instances in which, much like what happened with the Sackler family, donations have been given back or plaques have been removed from walls. Ideally, the institution has all the facts before depositing the check. He cites the example of a wealthy family from Asia who wanted to donate to an American campus in exchange for naming a building after a family member. Tasked by the university to delve deeper, Wealth-X found that the family was linked to fraud some 50 years prior, which was enough to convince the school to pass. “If you’re super-prominent, like an Ivy, you are under so much scrutiny,” says Garcia. Reputationally challenged donors have always been around, but in the 21st century, fundraisers increasingly must also contend with deep-fake donors. One Wealth-X client, Garcia says, was recently approached by someone who wanted to give a six-figure sum to a nonprofit that supports people in need of food and shelter. After some preliminary research, the client grew concerned the offer was too good to be true and enlisted Wealth-X, which determined that a photograph the donor sent of himself with the King of Spain was fake. “The real photo has a different person in it,” says Garcia, explaining that the faux donor was either photoshopped in or created by AI So why would someone manufacture a fake philanthropist? According to Garcia, either they were just messing around or they were attempting to launder money. “There’s not a lot of history of money laundering with not-for-profits, but you could give a big gift and then pull it back, and then it’s clean, right?”

A nonprofit also risks embarrassment if it accepts money from an entity that doesn’t align with its cause. “On the corporate side, we do have certain industries with whom we will not work,” says Luciana Bonifacio, chief development officer at Save the Children. “We would not engage with a tobacco company, right? So [there have been] situations like that, when we have turned donations away.” When it comes to individuals, it gets a bit murkier, and Bonifacio doesn’t think the same lens can be applied: can you hold someone accountable if they were once a senior executive for a company that runs counter to your mission, or if they pooled a stock fund where the questionable company is just one percent of their entire portfolio? While the well-known charity doesn’t have the capacity to comb through every donation, it will vet benefactors making significant contributions or who will be visible supporters. For the most part, Bonifacio says, donations come from high-net-worth individuals who sincerely want to add value to an organisation with a strong and positive purpose.

Good intentions aren’t necessarily enough to salvage a relationship. Greg Ratliff, senior vice president of advisory services at Rockefeller Philanthropy Advisors, which counsels individuals as well as foundations, says the group turned away a donor who wanted to create an anti-vaccination project at the height of Covid. Even when he worked at the Gates Foundation, he says, some organisations declined the mega-funder’s checks if they couldn’t agree on direction.

Museums and universities tend to have broader aims and constituencies than issue-focused nonprofits. Even so, in recent years, more and more donors and board members have been targetted. At the Museum of Modern Art, private equity magnate Leon Black decided not to stand for re-election as board chair after coming under fire for his ties to Jeffrey Epstein, the financier and convicted sex offender, but remains on the board. Warren B. Kanders resigned as vice chair of the Whitney Museum after repeated protests over his ownership of Safariland, a company that produces tear-gas canisters and other supplies used by the military and law enforcement. After Harvey Weinstein was outed as a serial sexual assaulter—but before he was criminally convicted—the University of Southern California bowed to backlash and rejected a US$5 million (around $7.95 million) pledge from the Hollywood power broker to create an endowment for female filmmakers.

Aaron Horvath, a sociologist and research scholar at the Stanford Center on Philanthropy and Civil Society, points to the case of Jeffrey Epstein, who tried to evade publicity—but maintain prestigious ties to MIT—by being listed as Anonymous on the roster of donors. “If you look at the Epstein gift to the MIT Media Lab, it raises a lot of questions about who we are taking money from,” he says. “I think people are more conscious of that now. There’s a broader critique going on in society about philanthropy, and I think that’s getting carried into the university. Places that might previously have skated by without much attention are now realising: we should probably draw up policy for how we’re going to deal with this kind of thing, or who we’re going to take money from. Stanford just kind of has its hat in its hand and is open to lots of philanthropy,” he adds. “There [are] serious questions to be raised about that.”

With donations becoming something of a minefield, more benefactors are seeking counsel. In order to mitigate any bad run-ins for her clients, Danielle Oristian York, executive director and president of 21/64, a company that advises multigenerational philanthropists, encourages them to find organisations that align with their values and to be clear on what their mission and vision are. “We call it their philanthropic identity,” she says.

It’s an important starting point, because not every situation is black-and-white. “I think there’s a need for conversation rather than cancelling,” she adds. “How do we have a conversation with the funder to understand their perspective and intention?” Even if an organisation does not initially condone a donor’s business record, there could be room to make a positive impact. In the past few years, she has also noticed a willingness from young givers to be more mindful in their philanthropic choices. “The way that wealth was created in previous generations can be seen as tainted or bad,” she says. “With new stewardship or leadership, generational wealth is now being repurposed for good.”

The same can be said for corporate foundations, where ethics can be nuanced. “We often work with corporations that are interested in addressing challenges in their supply chain and in their production process,” says Ratliff, from Rockefeller Philanthropy Advisors. He points to the Tiffany & Co. Foundation, an organisation that puts a lot of focus on land reclamation by restoring sites the company has damaged. “They’ve created amazingly beautiful parks around the world, but it’s in acknowledgement of what mining does and that the raw material for their goods and services are mined.”

Though much of the demand for consultants such as Xapien and Wealth-X may be motivated by the instinct for self-preservation, the simple act of vetting more benefactors, no matter how small their contributions, not only weeds out dirty donors but potentially gains more from the clean ones. Prospect research helps paint a better picture of the donor all-around—their hobbies, how much they’ve given to various causes, their liquid assets. “[You] might not think twice about that $25 donation, but in reality, they may be a very lucrative business owner or they may come from a very wealthy family,” says Vogt. “That $25 may actually turn into $25,000 or $250,000 or $2 million down the road.”

And it’s not just donees that benefit from all this scrutiny. For potential donors, being put under a microscope at the outset means they can minimise the risk of being embarrassed down the line. Because there are few things more humiliating than watching your name being chiselled off the walls of an illustrious institution.

With additional reporting by Mark Ellwood

Lead illustration: Boston Courthouse: Michael Dwyer/AP; Armstrong: Alexandre Marchi/Gamma-Rapho/Getty Images; Weinstein: Julia Nikhinson/Getty Images; Holmes: Jessica Rinaldi/ The Boston Globe/Getty Images; Cosby: Brendan Smialowski/Getty Images; Huffman and Macy: Joseph Prezioso/AFP/Getty Images; Oxy Dollars: Erik McGregor/Lightrocket/Getty Images; Protestors: Michael A. McCoy for the Washington Post/Getty Images; USC Pennant: Patrick T. Fallon for the Washington Post/Getty Images; Bankman-Fried: Michael M. Santiago/Getty Images; Epstein and Met: Getty Images

Subscribe to the Newsletter

Recommended for you

Double-Vision

What happens when Australia’s most compelling artists turn their gaze on each other? The answer is Artists by Artists, a striking new book from Arts-Matter founders Michelle Grey and Susan Armstrong.

October 27, 2025

My Hong Kong

As the buzz around the East Asian cultural mecca amplifies, who better than two savvy, on-the-ground locals to curate an insider’s guide to the city’s essential experiences.

October 27, 2025

You may also like.

You may also like.

Radek Sali’s Wellspring of Youth

The wellness entrepreneur on why longevity isn’t a luxury—yet—and how the science of living well became Australia’s next great export.

Australian wellness pioneer Radek Sali is bringing his bold vision for longevity and human performance to the Gold Coast this weekend with Wanderlust Wellspring—a two-day summit running 25-26 October 2025 at the RACV Royal Pines Resort in Benowa. Sali, former CEO of Swisse and now co-founder of the event and investment firm Light Warrior, has long been at the intersection of wellness, business and conscious purpose.

Wellspring promises a packed agenda of global thought leaders in biohacking and longevity, including Sydney-born Harvard researcher David Sinclair, resilience pioneer Wim Hof, performance innovator Dave Asprey and muscle-health expert Gabrielle Lyon. From immersive workshops to diagnostics, tech showcases, and movement classes, Sali aims to make longevity less a niche pursuit for the elite and more an accessible cultural shift for all. Robb Report ANZ recently interviewed him for our Longevity feature. Here is an edited version of the conversation.

You’ve helped bring Wellspring to life at a moment when longevity seems to be dominating the cultural conversation. What drew you personally to this space?

I’ve always been passionate about wellness, and the language and refinement around how we achieve it are improving every day. Twenty years ago, when I was CEO of Swisse, a conference like this wouldn’t have had traction. Today, people’s interest in health and their thirst for knowledge continue to expand. What excites me is that wellness has moved into the realm of entertainment—people want to feel better, and that’s something I’ve always been happy to deliver.

There are wellness retreats, biohacking clinics, medical conferences everywhere. What makes Wellspring different?

Accessibility. A wellness retreat can be exclusive, but Wellspring democratises the experience. Tickets start at just $79, with options up to $1,800 for a platinum weekend pass. That means anyone can learn from the latest thought leaders. Too often in this space, barriers are put up that limit who can benefit from the science of biohacking. We want Wellspring to be for everyone.

You’re not just an organiser, but also an investor and participant in this field. How do you reconcile passion with commercial opportunity?

Any investment I make has to have purpose. Helping people optimise their health has driven me for two decades. It’s satisfying not just as an investor but as an operator—it builds wonderful culture within organisations and makes a real difference to people’s lives. That’s the natural fit for me, and something I want to keep refining.

What signals do you look for in longevity ventures to separate lasting impact from passing fads?

A lot of what we’re seeing now are actually old ideas resurfacing, supported by deeper scientific research. My father was one of the first in conventional medicine to talk about diet causing disease and meditation supporting mental health back in the 1970s. He was dismissed at first, but decades later, his work was validated. That experience taught me to look for evidence-based practices that endure. Today, we’re at a point where great scientists and doctors can headline events like Wellspring—that’s a huge cultural shift.

Longevity now carries a certain cultural cachet—its own insider language and status markers. How important is that to moving the field forward?

Health is our most precious asset, and people have always boasted about their routines—whether it’s going to the gym, doing a detox, or training for a marathon. What’s different now is that longevity practices are gaining mainstream recognition. I see it as something to be proud of, and I want to democratise access so everyone can ride the biohacking wave.

But some argue that for the ultra-wealthy, peak health has become a kind of luxury asset—like a private jet or a competitive edge.

That’s short-sighted. Yes, there are extremes, but most biohacking methods are accessible and inexpensive. Look at the blue zones—their lifestyle practices aren’t costly, yet they lead to long, healthy lives. That’s essential knowledge we should be sharing widely, and Wellspring is designed to do that in an engaging way.

Community is often cited as a key factor in healthspan. How does Wellspring foster that?

Community is at the heart of it. Just as Okinawa thrives on social connection, we want Wellspring to be a regular gathering place where people uplift each other. Ideally, it would become as busy as a Live Nation schedule—but for health and wellness.

Do you worry longevity could deepen class divides?

Class divides exist, and health isn’t immune. But in Australia, we’re fortunate—democracy and a strong equalisation process help maintain quality of life for most. Proactive healthcare, like supplementation and lifestyle changes, isn’t expensive. In fact, it’s cheaper than a daily coffee. That’s why we’re one of the top five longest-living nations. The opportunity is to keep improving by making proactive health accessible to everyone.

Some longevity ventures are described as “hedge-fund moonshots.” Others, like Wellspring, seem grounded in time-tested approaches. Where do you stand?

There’s value in both, but I’m more interested in sensible, sustainable practices. Things like exercise, meditation, and community-driven activities are proven to extend life and improve wellbeing. Technology can support this, but we can’t lose sight of the human elements—connection, balance, and purpose.

Finally, what role can Australia—and Wellspring—play in shaping the global longevity conversation?

The fact that we can put on an event like Wellspring, attract world-leading talent, and already have commitments for future years says a lot. Australia is far away, but that hasn’t stopped great scientists and thinkers from coming. We’ll be here every year, contributing to the global conversation and, hopefully, helping more people extend their healthspan.

You may also like.

‘Continuum’ Opens to Rave Applause at Sydney Dance Company

Rafael Bonachela’s latest curatorial triumph premiered last night at the Roslyn Packer Theatre, dazzling audiences with its emotional range and fearless physicality.

Sydney Dance Company opened its latest season with Continuum, a triple bill that reminds audiences why the ensemble remains Australia’s most compelling cultural export. Receiving a standing ovation at its premiere last night at the Roslyn Packer Theatre, the program unfolds as an elegant meditation on movement and metamorphosis—three distinct choreographic visions held together by Rafael Bonachela’s curatorial precision and instinct for contrast.

Stephen Page’s Unungkati Yantatja – one with the other breathes land, sea, and sky into motion; Tra Mi Dinh’s Somewhere between ten and fourteen lingers in the tender light between day and night; and Bonachela’s own world-premiere Spell delivers the evening’s visceral heartbeat. Together they trace the continuum of life itself—fluid, volatile, and impossible to pin down. Running through 1 November, the production affirms Bonachela’s vision of dance as “an ever-evolving conversation between artists, audiences, and the world around them.” Robb Report ANZ recently caught up with Bonachela.

Continuum is described as “a bold exploration of the ever-shifting cadence that binds us to the world.” How did this idea of constant transformation influence your choreographic choices in Continuum?

I’ve curated this evening as an invitation for audiences to experience dance as an ever-evolving conversation—between past and present, between the individual and the collective, and between diverse artistic voices. My intention with this program is to spark connection, curiosity, and reflection, offering works that challenge, move, and inspire while revealing the transformative power of the body in motion.

Each choreographer brings a distinct perspective, yet all share a commitment to exploring the body in motion as a vessel for transformation. Through contrasting aesthetics, cultural resonances, and shifts in time, these works reveal how dance exists on a continuum—where moments build upon one another, find new meanings in fresh contexts, and affirm the enduring power of the human form to express what words cannot.

You’ve created the world premiere Spell within Continuum, which explores “the limits of emotional and physical expression.” What did you aim to conjure emotionally and physically through Spell, and how does it dialogue with the other works in the triple bill?

The title Spell itself suggests a duality—it can be something magical, but also something we fall under without even realising. Emotionally, I want to evoke an atmosphere that is at once intimate and volatile, where vulnerability and power exist side by side. There’s a ritualistic quality to the work, as if the dancers are caught inside a force they cannot quite escape—and it’s that tension which drives the movement and fuels the piece.

Within Continuum, Spell emerges as an intense, visceral heart—both contrasting with and speaking to the other works. While it shares the evening’s theme of transformation, it explores it through a lens of emotional ignition and fearless physicality.

In crafting Continuum, how did you balance moments of intimacy and expansiveness—especially when layering live elements like music and immersive lighting—to evoke that ebb and flow of life’s narratives?

In Continuum, each choreographer works with complete artistic freedom, without any direction from me. That independence brings out authentic contrasts and unexpected connections between the works. It’s this variety that invites audiences to engage on their own terms, discovering personal meanings and emotional threads that are unique to each viewer.

This triple bill seems to offer a journey through time and place—from twilight’s fleeting beauty to elemental breath. How do you want audiences to experience—and perhaps rethink—the relationship between movement, nature, and storytelling?

I always want audiences to come with an open mind and allow the experience to be unprescribed free to discover their own meanings and narratives. Dance has the unique power to be felt as much as it is seen, to resonate physically and emotionally in ways words can’t. I hope audiences leave with a renewed sense of how deeply movement is connected to the natural world, and how it can tell stories without language. Like nature, this evening is always in motion—emerging, transforming, and fading—so that each work becomes a landscape the audience can journey through, sensing their own place in the continuum of life

Looking ahead, does Continuum carve out a new direction or personal milestone for your artistic trajectory? What might this signal for your future choreographic explorations?

Continuum feels like both a culmination and a starting point. It gathers threads from my past work, my fascination with transformation, my love of collaboration, my search for emotional truth and weaves them into something that opens new doors.

Creating and curating this triple bill has changed how I see works interacting—how contrasting voices can strengthen shared themes. It’s inspired me to explore even more fluid boundaries between ideas, styles, and disciplines.

If it signals anything for the future, it’s that I’m interested in going further into that space where dance is not just movement, but an ongoing conversation—between artists, between forms, and between audiences and the world around them.

Continuum runs through November 1 at the Roslyn Packer Theatre.

You may also like.

Inside the $30 Billion Obsession Among the Ultra-Wealthy : A Race to Live Longer

The pursuit of an extended life has become a new asset class for those who already own the jets, the vineyards, and the art collections. The only precious resource left to conquer, it seems, is time.

If you want to know what the latest obsession is these days among the ultra-wealthy, listen in at dinner.

Once it was crypto, then came AI and psychedelics, now it’s longevity all the time. The talk is of biomarkers, NAD+ levels, and methylation clocks, of senolytics and stem cells. Guests compare blood panels like wine lists, and the most important name to drop is no longer your banker or contact at Rolex but your longevity physician. For those just arriving at the conversation, the new science can sound like science fiction—but it’s fast becoming the lingua franca of money.

The field has its own vocabulary—epigenetic reprogramming, which aims to reset cellular clocks; cellular senescence clearance, the removal of “zombie” cells that clog our systems as we age; precision gene therapies, designed to personalise interventions at the level of DNA—that sounds equal parts Brave New World and Wall Street pitch deck. But make no mistake: this is no longer a niche pursuit. The sector is already worth an estimated $30 billion globally and projected to surpass $120 billion within the decade, having attracted billions in investment from the likes of Altos Labs, Juvenescence and Google-backed Calico. Tech titans and old-money families alike are staking claims on the possibility of an extra decade or two. It’s a space where venture funds court Nobel laureates, hedge funds bankroll gene-therapy moonshots, and even wellness festivals in Australia draw rock-star scientists to the stage.

The Poster Child and the Pitch

David Sinclair, the Sydney-born Harvard geneticist who has become something of a poster child for the field, is quick to underline the stakes. “We’re not just talking about lifespan, we’re talking about health span,” he tells Robb Report. “Extending the number of years people live well—without frailty, without disease—isn’t just a medical breakthrough. It’s a social and economic one.” Sinclair, whose research ranges from NAD boosters to epigenetic age-reversal therapies, has calculated that adding a single year of healthy life to the US population, for example, could be worth $38 trillion in economic benefit—fewer years of costly aged care, less burden on hospitals, more years of productivity and compounding returns. In other words, the dividends of health are financial as well as personal. “That’s why governments and investors are paying attention,” he says.

Sinclair has become a fixture on the global circuit, drawing crowds that rival TED or Davos. As Radek Sali, the Australian entrepreneur behind the new Wanderlust Wellspring longevity festival taking place on the Gold Coast this October, where Sinclair is the keynote speaker, puts it: “Wellness has moved into the realm of entertainment.” At Wellspring, platinum-tier guests pay up to nearly $2,000 for the privilege of hearing scientists and investors share the stage over a weekend like headliners at Coachella.

Investing in Time

And then there are the sideshows. Bryan Johnson, the tech mogul turned human guinea pig, makes headlines with his open-source, organ-by-organ data tracking—his infamous “penis readings” have become cocktail-party fodder. While many dismiss him as a parody of the field, his multimillion-dollar project Blueprint has nevertheless made longevity impossible to ignore in the mainstream.

For the uninitiated, the science of longevity today is no longer about vitamin salesmen or fringe dietary regimes. This is the new frontier—one where biology is not just observed but engineered, and where investors smell opportunity on par with space travel. It’s little wonder that Altos Labs has raised billions to chase cellular rejuvenation, or that Juvenescence has secured more than $400 million to fast-track therapies. What was once the realm of eccentric tinkerers now attracts sovereign wealth funds.

“This body takes me to meetings, earns me money—why not invest time and money into it?”

The appeal to the One Percent is obvious. Longevity is a natural extension of portfolio thinking: diversify your assets, hedge your risks, and above all, maximise return on investment. Except in this case, the returns are measured in years of health, energy and cognition. As Andrew Banks, a Sydney-based entrepreneur and early investor in Juvenescence, explains: “This body takes me to meetings, earns me money—why not invest time and money into it?” His Point Piper home teems with contraptions—a Reoxy breathing machine, hydrogen therapy, red-light sauna, and he spends a few hours a day on maintenance, as if his body were a private equity stake.

Banks, like others in his cohort, is baffled that more wealthy men haven’t followed suit. “Entrepreneurs pride themselves on divergent thinking,” he says. “They expand, dream and create businesses with it. But when it comes to their bodies, they’re convergent—unimaginative. The lack of curiosity is astonishing to me.”

Medicine 3.0 and the New Rituals

Steve Grace, a Sydney-based entrepreneur and the proprietor of exclusive private networking club The Pillars, which is opening a longevity program, thinks there is a reckoning coming for those who do not take matters into their own hands. “As someone who has run a few recruitment businesses,” he says, “I can tell you that if you’re a man or woman in your 50s and working as an employee, even in a really good position, it’s time to get worried about job security and being aged out of the workforce. You have to make yourself as vital as possible and become the best version of yourself, or you’re toast.”

What was once fringe has now become a cultural necessity for those who can afford anything, with science finally catching up to ambition. Sinclair’s lab at Harvard recently published a study on the reversibility of cellular ageing—restoring vision in blind mice and setting the stage for human trials in conditions like glaucoma. In Boston, his company Life Biosciences will begin treating patients with blindness in a Phase I trial using partial cellular reprogramming early next year. “This isn’t science fiction anymore,” Sinclair says. “We’re at the point where we can reprogram cells, turn back their biological clocks, and restore function.”

Meanwhile, practitioners like Dr. Adam Brown of the Longevity Institute in the Sydney suburb of Double Bay are reinventing diagnostics. His “assessment menu” has been compared—only half-jokingly—to a Michelin Guide for medical testing: full-body MRI scans, continuous glucose monitors, polygenic risk scores. “What we do is proactive, not reactive,” he says. “Correct deficiencies first, then optimise health. That’s how you get peak performance in the short term and resilience in the long term.” Brown frames longevity in terms that would resonate with any investor: “There’s a short-term ROI—fixing glucose or sleep issues so you perform better tomorrow. And there’s a long-term ROI—functioning in your 70s as you would in your 40s. That’s extending your career, your income potential and your independence.”

“Once upon a time, male vanity meant injectables, veneers and a tan. Today, it’s VO2 max scores and continuous glucose monitor readouts.”

Peter Attia, the Canadian-American physician and podcast host who has helped popularise the concept of “Medicine 3.0”, echoes this emphasis. Medicine 1.0, according to him, was about surviving infections. Medicine 2.0 was about treating chronic disease. Medicine 3.0 is about staying ahead of decline: measuring, monitoring and intervening early. “The goal is not just to avoid disease but to lengthen health span,” Attia has said.

For those already converted, longevity is less about lab science than daily rituals. Sydney-based Chief Brabon, who trains CEOs like athletes, says: “These men are like Formula One cars—you don’t wait until the tyres are bald before swapping them. You keep everything tuned, precise, optimised.”

That tuning now involves more gadgets than ever: hyperbaric oxygen chambers, cryotherapy, sauna/cold-plunge circuits, peptide stacks, nootropics. And yes, a glut of supplements, some with evidence, others little more than wishful thinking. Once upon a time, male vanity meant injectables, veneers and a tan. Today, it’s VO2 max scores and continuous glucose monitor readouts. “Health is the new flex,” as Steve Grace quipped, glancing at his wrist-worn biometric tracker.

The New Flex: Health as the Ultimate Luxury

Still, there is plenty of scepticism. Some therapies are unproven, others prohibitively expensive. And there is the unavoidable fact that many leading scientists, including Sinclair, have stakes in companies producing supplements and therapeutics, raising eyebrows about conflicts of interest. “The difference,” Sinclair insists, “is whether it’s backed by peer-reviewed science and measurable biomarkers. If it can’t be quantified, it’s marketing, not medicine.”

Then there are the contradictions. It promises democratisation while often priced like a private club. It champions science but thrives on hype. It seeks to extend health span but risks deepening class divides. “Only if we let it,” Sinclair says when asked if longevity risks becoming the preserve of the wealthy. “Like antibiotics or aspirin, these advances should become widely available and affordable once they scale.” Sali agrees, but from another angle: “Biohacking doesn’t have to be expensive,” he says. “The blue zones prove that—community, diet, movement, purpose. Those are free. Wellspring is about making that knowledge accessible.”

And yet, for all its shortcomings, the movement is here to stay. Investment continues to pour in. Technology—like senolytic drugs that clear aged cells or AI-driven platforms that predict individual disease risk years in advance—is moving from speculation to clinical trial. Scientists are being recast as influencers. And the wealthy, always in search of the next advantage, have found in longevity a pursuit as old as alchemy, yet dressed in the language of venture capital. The truth is that health has always been an asset. What’s new is that it’s now being traded, optimised and measured like one.

In the end, longevity is less about a moonshot than about curiosity. Banks, Sali, Sinclair, Attia are all, in their own way, betting on time. Perhaps the most radical idea is also the simplest: that the best-performing asset in any portfolio is the body itself. Unlike Bitcoin, it carries you to meetings. Unlike art, it cannot be stored in a vault. Unlike real estate, it is non-transferable.

The new calculus of longevity is the recognition that the ultimate luxury is not wealth or status, but a few more decades of clear thought, strong bones and good company—and the ability to make money off it. Everything else, as one investor put it, is just a rounding error.

You may also like.

How Sailing Shaped Loro Piana’s Most Iconic Designs

Pier Luigi Loro Piana grew his family textile business into a celebrated fashion house by following his passion for sports on land and at sea.

The Regatta Connection

The race village at Port de Saint-Tropez is awash with people in nautical navy and white, the de facto dress code for the Loro Piana Giraglia regatta. This is the second year the fashion house has lent its name to one of the Mediterranean’s most prestigious summer races. The course zooms from the French coast to Genoa, Italy, taking a sharp turn past Giraglia, a small island off Corsica’s northern tip. It’s the latest in a long line of marine events the brand has sponsored, dating back more than 20 years.

The link between sailing and the brand—and more consequentially the Loro Piana family—is exemplified by the man Robb Report is here to meet: Pier Luigi Loro Piana. An avuncular figure in his 70s with the physique of a man who has enjoyed life, Pier Luigi fell in love with sailing in his late teens, when a family friend took him for a cruise in a sloop.

“Using the wind to go faster or slower, driving the boat like it has an engine, it’s really fascinating,” he says. Inevitably, he started competing. “When you’re sailing, you’re always looking for other boats to go and fight with. It’s an instinct,” he says. And then, with considerable understatement, “I think it’s a nice hobby.”

A Life Under Sail

He currently owns two boats: My Song, which you can see on these pages, is a 25 m sailing yacht that competed in the Regatta. There’s also Masquenada, a comfortable 50 m explorer. It’s a commendable set-up befitting a man who shaped one of Europe’s most celebrated fashion houses.

A Family Business Turned Global Powerhouse

The textile and clothing company that bears his family’s name was launched by an ancestor, Pietro Loro Piana, in 1924. A few generations later, Pier Luigi and his brother, Sergio, would run it for four decades until LVMH acquired a majority stake for around $4 billion in 2013. Sergio passed away that year; his widow and Pier Luigi still own a share of the brand between them.

The brothers proved innovative custodians, moving the company upmarket with an insistence on ultra-fine materials and groundbreaking fabrications. And the connection with sports—specifically yachting, horseback riding, skiing and golf—is integral to how the brand positions itself. As Pier Luigi recalls, such associations often had self-serving origins.

“These are the sports my brother and myself were doing,” he says. “We were very committed in business in the 1970s, ’80s, ’90s, so we were like our customers: people that like to work hard but also play hard. And that meant sports.”

Innovation Born of Necessity

This affinity often led them to develop durable, yet elegant, materials and gear for their off-duty pursuits, eventually offering versions to their athletic clientele. “We engineered products with unusual properties, natural fibres like wool or cashmere with a membrane that makes it waterproof and windproof… For research and development, I was the first victim,” he says with a chuckle. Once, he wanted a ski jacket that was “warmer, lighter, softer and better” than nylon models, so he made a prototype to test on the slopes. It gave birth to the Loro Piana Storm System, launched in 1994. The line’s wind-resistant waterproof wool and cashmere has since been used by brands around the world. “I still have this jacket,” he says.

The same process happened on the water. A beloved reversible bomber, with knitted cashmere on one side and waterproof polyester on the other, was born from Pier Luigi’s need for a functional jacket to wear on his yacht. “It’s very light, doesn’t wrinkle, it’s warm, windproof,” he says. “It solves so many problems.”

He takes less credit for perhaps the brand’s most famous—and almost certainly most imitated—product, the white-soled suede Summer Walk loafers. “That was my brother,” he says. “When we were 20, 30 years old, we went sailing and there were only [Sperry] Top-Siders or Sebagos. But when the soles got worn, they got hard and slippery.”

The answer: a non-marking sole with grip—“like a tire you use in Formula 1 when it’s wet”—which Sergio got his bespoke shoemaker to sew to suede uppers. Eventually, they produced two versions: a loafer and the Open Walk, a model with a slightly higher top. “We discovered people were using them also for formal wear because they were so comfortable,” says Pier Luigi. “It’s really a successful story that started from product research.”

And if problem-solving can turn your family business into a giant of global style, clearly it pays to be a little selfish.

You may also like.

The Supercar of Pool Tables

In a rare fusion of Italian design pedigree and artisanal craftsmanship, Pininfarina and Brandt have reframed the barroom game as aerodynamic high art.

In the rarefied realm where leisure meets design, the latest object of desire doesn’t purr down the autostrada—it commands the room from a single sculptural base. The Vici pool table, a collaboration between Italian automotive legend Pininfarina and Miami’s bespoke table-maker Brandt Design Studio, reimagines the game with the same aerodynamic poise and artisanal precision that have graced some of the world’s most beautiful vehicles.

Named for Julius Caesar’s immortal boast—“Veni, vidi, vici”—this limited-edition series transforms billiards from casual diversion into a declaration of style. Every curve is deliberate, from the ultra-thin playing surface clad in tournament-grade Simonis cloth to the seamless integration of Italian nubuck leather and precision-milled metals. The effect is more haute sculpture than barroom pastime—yet it meets exacting professional standards.

For the true connoisseur, the debut PF 95 Anniversario edition celebrates Pininfarina’s 95-year legacy in just 95 numbered pieces. Finished in dark-blue lacquer with rose-gold accents and a flash of red felt, each table is discreetly nameplated—a tangible claim to an heirloom in the making.

“It’s not just about how it plays—it’s about how it lives in a space,” says Dan Brandt, the master craftsman whose work has long graced the world’s most exclusive interiors. Whether anchoring a penthouse salon, a members’ lounge or the main deck of a superyacht, the Vici is designed to stir conversation before the first break.

For those accustomed to Pininfarina’s sleek automotive silhouettes, this is a chance to bring that same lineage of movement, form and Italian refinement into the home. Only now, the horsepower is measured not in engines—but in the geometry of a perfect shot.

From pool to midcentury to Ottoman, we’ve got all the table angles covered at Robb Report Australia & New Zealand —plus more home-worthy pieces.