Robb Reader: Audemars Piguet’s Michael L. Friedman

Fascinated in mechanics, engineering and time itself from his formative years, his career path has been driven by an insatiable hunger for knowledge. We caught up with Michael Friedman at SIHH in Geneva.

Related articles

What first drew you to watchmaking?

As a child, I was drawn to how things work. I always wanted to figure out processes. I wanted to understand the basics of how things worked: and why. It’s done this way? Why? You have to do this? Why? Why, why, why! Part of being the youngest of three boys is, you’re pretty precocious in those situations. Your brothers inevitably bring you up. We would take things apart – usually without being very good at putting them back together.

Did you have formal education in horology?

My rebellious spirit fuelled my academic and intellectual pursuits when I went to university, where I initially studied cultural studies through the lens of psychology. I became immensely interested in how different cultures have measured time throughout history, in what the nature of time is and how time is experienced culturally, historically, neurologically. I became obsessed with time theory.

How did you turn this obsession into a career?

My first jobs were working in watch and clock museums back in around 1995, 1996 – the New England Science Center (now called EcoTarium), the Willard House & Clock Museum – then I took over as Head Curator at the National Watch and Clock Museum. Watches and clocks weren’t very cool at that point, and the older generation were so happy to have this young guy they could just feed information to. I spent time working behind the bench – not to become a watchmaker, but just to understand the process – and I became super-sensitive to restoration, because one of my mentors, Robert Chaney, one of the world’s foremost experts on mechanical clocks, taught me all about it: what’s right, what’s wrong, how to identify, how not to identify..

How did you first encounter Audemars Piguet?

My paths first crossed with Audemars Piguet’s in 2000. I was Head of Watches at Christies in New York; François-Henry (Bennahmias) was CEO of Audemars Piguet North America. We were both an awful lot younger. We teamed up for Audemars Piguet’s Time To Give Celebrity Watch Auction For Charity, held at Christie’s Auction House in New York City, with Billy Crystal, Muhammad Ali and Arnold Schwarzenegger. It was an important moment for everyone – meeting Muhammad Ali possibly being one of the most important moments ever. That event was when I realised that this is a very different company: the energy, the spirit of that company was unlike anything I’d experienced, and it resonated. We remained in touch, and I began collecting their watches.

What is it about Audemars Piguet’s history that resonates?

This isn’t a story that begins with the Royal Oak in 1972 – it had been happening for decades prior. The Royal Oak is part of a continuum – it didn’t happen in isolation or a vacuum – Jenta had designed many watches for AP before it and he was certainly cognisant of the design history of the company when he went into that. That history and that background is what gave the Royal Oak the context to arrive when it did. Every single creation was unique before 1951. You won’t find two Audemars Piguet watches from before then that are identical – you might find two that are similar, but reference numbers and model numbers don’t come with our company until that year, and we were a tiny manufacturer. The evolution of the pocket watch and the wristwatch is when things get incredibly creative in AP because that’s when they realise they have a new canvas, a new platform, new shapes to work with. You can only show complex polishings if you have geometrical form, and that remains what the brand still does: decorations, polishings, finishings.

What, for you, are the other major milestones in the brand’s history?

Reference 5516 – the world’s first perpetual calendar wristwatch with leap year indicator – is one. Our friends at Patek had introduced the Perpetual in 1941 but without a leap year. It was a small watch – they evolved it over time – but the 1955 Perpetual Calendar is a landmark in the history of watchmaking. Only us and Patek, before the 80s, made perpetual wristwatches in a series. Another, I’d say, is the 2002 30th Royal Oak Anniversary concept: that introduced 21st Century horology; it was looking to the future without hesitation, through the lens of haute horology. It also showcased a balance between hand-finishing and techniques with advanced systems.

Are horological tastes and preferences ubiquitous?

No. Different countries have different aesthetics. When you see who historic watches are sold to it makes sense: one sold in 1936 in Italy, you feel it, you see it; a watch sold in New York in Paris in 1924 will have unapologetic art deco aesthetics with strong geometric lines. Cultural history is inextricably connected to our history. We’ve been embracing culture since the 1899 Paris exhibition.

How does the new Code 11.59 range nudge Audemars Piguet’s history forward?

The Code 11.59 is on the pulse, on the edge, of the moment. It adopts codes not just from the design history of Audemars Piguet, but also those of today, and even looking outside of watchmaking. The double curved, domed, glare-proof sapphire crystal really improves clarity, legibility. The sculpture of the lugs, too, calls to mind modern architecture. Our watches need to showcase the human touch – the work of the finishers, the polishers, all that incredible decoration. The insertion of that octagonal middle case means the polishers and decorators have a canvas with which to express themselves and our tradition. Today we only have ten people in the entire company who hand-finish Code 11.59, and all of them are the very best experts we have.

What does the word luxury mean to you?

Luxury is a word I never use any more. It’s increasingly hard to know what people mean by it. Price points? Branding? It’s hard to even pin down what the difference is in the case of a publicly traded entity compared to a family-run business. It means very different things. So for me, time itself is luxury. The time we give the finishers and the engineers and the craftsman to put in to their creativity; luxury is about the humanity that goes into the watch you’re wearing.

Is the young, modern watch aficionado a different beast to his or her predecessors?

Gen-Z is the first generation to grow up entirely in the era of obsolescence – that’s their reality. Everything is upgradable, replaceable, temporary – so their love of mechanical watches comes from the fact that they stand in defiance to that trend. They’re all about permanence in an era dominated by obsolescence. Looking at a 22-year-old wearing an Audemars Piguet watch, what’s incredible is that in 50 years’ time it’s going to be on the wrist of his or her kid. And it’s still going to resonate, and represent this moment right here and now just like the 1972 Royal Oak does. That’s exciting.

So you feel that mechanical watches hold an appeal for techie types?

Yes – these are objects were advanced technologies themselves before the advent of Quartz and cesium atomic clocks. They were the apex of science and technology in the late 19th Century: surveying, navigation, any scientific analysis required accurate time measurement. The whole history of science and technology is anchored to time measurement. The Hadron Collider in Cern only functions because it’s anchored to the atomic clock.

How does Audemars Piguet go about selecting commercial partners?

We like to explore outside of watchmaking as well as inside of it – cultural connection, cultural engagement. That’s why we do Art Basel. It’s why we sponsor the Montreux Jazz Festival. It’s why we engage athletes and chefs. Many of the people we pick to have relationships with aren’t that high-profile: it’s not about getting news articles – it’s about giving our clients, both potential and existing, the opportunity to engage in these dialogues in a non-transactional format and think more about form and function and design and aesthetics and time itself in different cultural contexts. You need that humanity – not just behind the work bench but in front of the client too.

How important is it for brands to educate watch lovers?

We feel a weight on our shoulders: an imperative to show respect to the artisans and craftspeople and engineers and technicians. Because people don’t talk about this enough in this business – there’s too much talk about product and not enough about process. That’s the emotional connection. When clients visit us at Vallée de Joux, see the museum, the workshop, that’s when the emotional connection happens. That’s why we’re expanding the museum, and doing the Audemars Piguet Hôtel des Horlogers on the slopes of the Vallée de Joux. We want to do everything we can to bring people into that environment.

Subscribe to the Newsletter

Recommended for you

Watches & Wonders 2024 Showcase: Hermès

We head to Geneva for the Watches & Wonders exhibition; a week-long horological blockbuster featuring the hottest new drops, and no shortage of hype.

By Josh Bozin

July 24, 2024

Watch This Space: Mike Nouveau

Meet the game-changing horological influencers blazing a trail across social media—and doing things their own way.

By Josh Bozin

July 22, 2024

You may also like.

By Josh Bozin

24/07/2024

You may also like.

5 Lounge Chairs That Add Chic Seating to Your Space

Daybeds, the most relaxed of seating solutions, offer a surprising amount of utility.

Chaise longue, daybed, recamier, duchesse brisée—elongated furniture designed for relaxing has a roster of fancy names. While the French royal court of Louis XIV brought such pieces to prominence in fashionable European homes, the general idea has been around far longer: The Egyptian pharaohs were big fans, while daybeds from China’s Ming dynasty spurred all those Hollywood Regency fretwork pieces that still populate Palm Beach living rooms. Even Mies van der Rohe, one of design’s modernist icons, got into the lounge game with his Barcelona couch, a study of line and form that holds up today.

But don’t get caught up in who invented them, or what to call them. Instead, consider their versatility: Backless models are ideal in front of large expanses of glass (imagine lazing on one with an ocean view) or at the foot of a bed, while more structured pieces can transform any corner into a cozy reading nook. Daybeds may be inextricably linked to relaxation, but from a design perspective, they put in serious work.

Emmy, Egg Collective

In designing the Emmy chaise, the Egg Collective trio of Stephanie Beamer, Crystal Ellis and Hillary Petrie, who met as students at Washington University in St. Louis, aimed for versatility. Indeed, the tailored chaise looks equally at home in a glass skyscraper as it does in a turn-of-the-century town house. Combining the elegance of a smooth, solid oak or walnut frame with the comfort of bolsters and cushioned upholstery or leather, it works just as well against a wall or at the heart of a room. From around $7,015; Eggcollective.com

Plum, Michael Robbins

Plum, Michael Robbins

Woodworker Michael Robbins is the quintessential artisan from New York State’s Hudson Valley in that both his materials and methods pay homage to the area. In fact, he describes his style as “honest, playful, elegant and reflective of the aesthetic of the Hudson Valley surroundings”. Robbins crafts his furniture by hand but allows the wood he uses to help guide the look of a piece. (The studio offers eight standard finishes.) The Plum daybed, brought to life at Robbins’s workshop, exhibits his signature modern rusticity injected with a hint of whimsy thanks to the simplicity of its geometric forms. Around $4,275; MichaelRobbins.com

Kimani, Reda Amalou Design

French architect and designer Reda Amalou acknowledges the challenge of creating standout seating given the number of iconic 20th-century examples already in existence. Still, he persists—and prevails. The Kimani, a bent slash of a daybed in a limited edition of eight pieces, makes a forceful statement. Its leather cushion features a rolled headrest and rhythmic channel stitching reminiscent of that found on the seats of ’70s cars; visually, these elements anchor the slender silhouette atop a patinated bronze base with a sure-handed single line. The result: a seamless contour for the body. Around $33,530; RedaAmalou

Dune, Workshop/APD

From a firm known for crafting subtle but luxurious architecture and interiors, Workshop/APD’s debut furniture collection is on point. Among its offerings is the leather-wrapped Dune daybed. With classical and Art Deco influences, its cylindrical bolsters are a tactile celebration, and the peek of the curved satin-brass base makes for a sensual surprise. Associate principal Andrew Kline notes that the daybed adeptly bridges two seating areas in a roomy living space or can sit, bench-style, at the foot of a bed. From $13,040; Workshop/ APD

Sherazade, Edra

Designed by Francesco Binfaré, this sculptural, minimalist daybed—inspired by the rugs used by Eastern civilizations—allows for complete relaxation. Strength combined with comfort is the name of the game here. The Sherazade’s structure is made from light but sturdy honeycomb wood, while next-gen Gellyfoam and synthetic wadding aid repose. True to Edra’s amorphous design codes, it can switch configurations depending on the user’s mood or needs; for example, the accompanying extra pillows—one rectangular and one cylinder shaped— interchange to become armrests or backrests. From $32,900; Edra

You may also like.

By Josh Bozin

24/07/2024

22/07/2024

Watches & Wonders 2024 Showcase: Hermès

We head to Geneva for the Watches & Wonders exhibition; a week-long horological blockbuster featuring the hottest new drops, and no shortage of hype.

With Watches & Wonders 2024 well and truly behind us, we review some of the novelties Hermès presented at this year’s event.

—

HERMÈS

Moving away from the block colours and sporty aesthetic that has defined Hermès watches in recent years, the biggest news from the French luxury goods company at Watches & Wonders came with the unveiling of its newest collection, the Hermès Cut.

It flaunts a round bezel, but the case middle is nearer to a tonneau shape—a relatively simple design that, despite attracting flak from some watch aficionados, works. While marketed as a “women’s watch”, the Cut has universal appeal thanks to its elegant package and proportions. It moves away from the Maison’s penchant for a style-first product; it’s a watch that tells the time, not a fashion accessory with the ability to tell the time.

Hermès gets the proportions just right thanks to a satin-brushed and polished 36 mm case, PVD-treated Arabic numerals, and clean-cut edges that further accentuate its character. One of the key design elements is the positioning of the crown, boldly sitting at half-past one and embellished with a lacquered or engraved “H”, clearly stamping its originality. The watch is powered by a Hermès Manufacture movement H1912, revealed through its sapphire crystal caseback. In addition to its seamlessly integrated and easy-wearing metal bracelet, the Cut also comes with the option for a range of coloured rubber straps. Together with its clever interchangeable system, it’s a cinch to swap out its look.

It will be interesting to see how the Hermès Cut fares in coming months, particularly as it tries to establish its own identity separate from the more aggressive, but widely popular, Ho8 collection. Either way, the company is now a serious part of the dialogue around the concept of time.

—

Read more about this year’s Watches & Wonders exhibition at robbreport.com.au

You may also like.

22/07/2024

Living La Vida Lagerfeld

The world remembers him for fashion. But as a new tome reveals, the iconoclastic designer is defined as much by extravagant, often fantastical, homes as he is clothes.

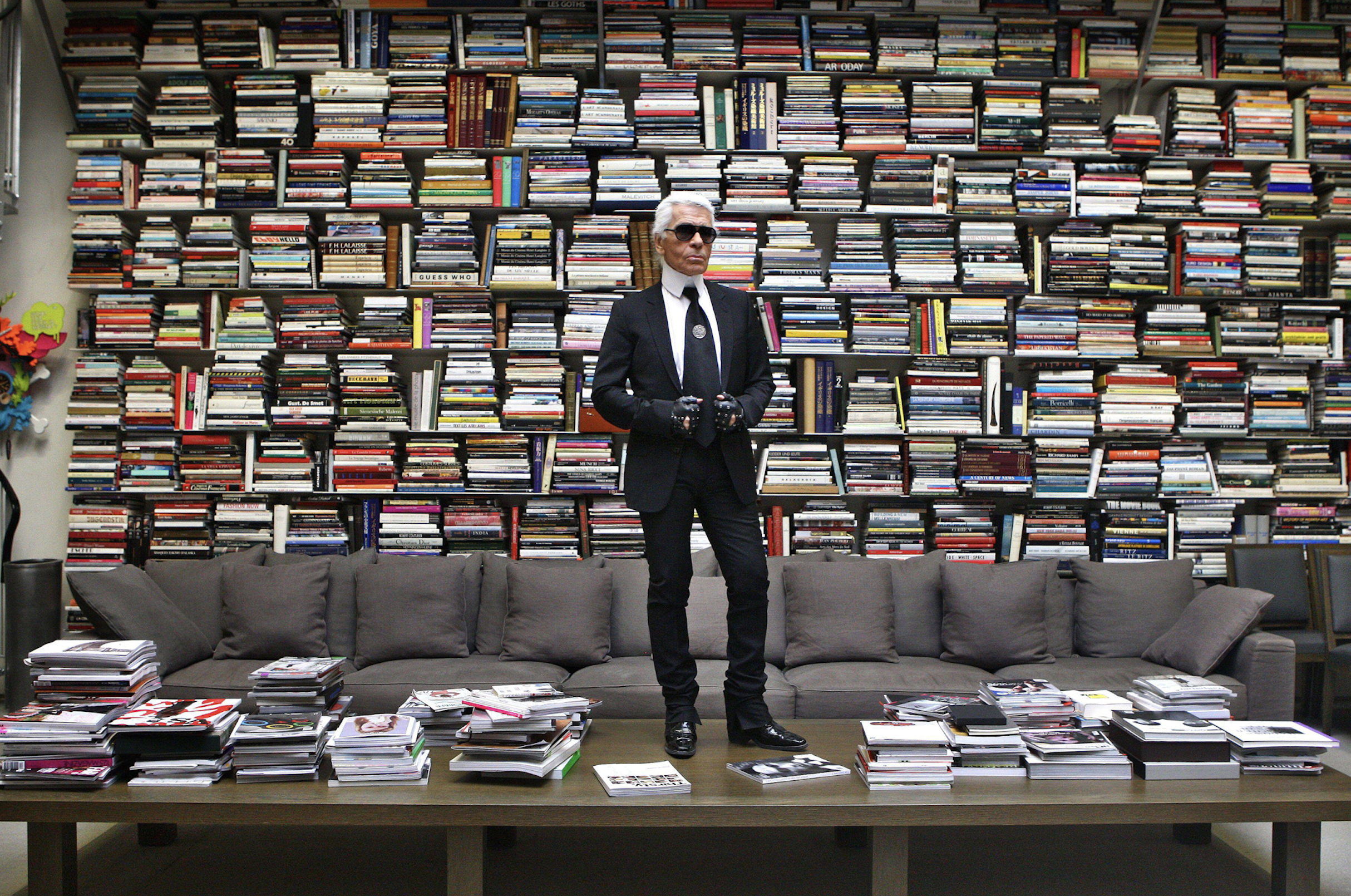

“Lives, like novels, are made up of chapters”, the world-renowned bibliophile, Karl Lagerfeld, once observed.

Were a psychological-style novel ever to be written about Karl Lagerfeld’s life, it would no doubt give less narrative weight to the story of his reinvigoration of staid fashion houses like Chloe, Fendi and Chanel than to the underpinning leitmotif of the designer’s constant reinvention of himself.

In a lifetime spanning two centuries, Lagerfeld made and dropped an ever-changing parade of close friends, muses, collaborators and ambiguous lovers, as easily as he changed his clothes, his furniture… even his body. Each chapter of this book would be set against the backdrop of one of his series of apartments, houses and villas, whose often wildly divergent but always ultra-luxurious décor reflected the ever-evolving personas of this compulsively public but ultimately enigmatic man.

With the publication of Karl Lagerfeld: A Life in Houses these wildly disparate but always exquisite interiors are presented for the first time together as a chronological body of work. The book indeed serves as a kind of visual novel, documenting the domestic dreamscapes in which the iconic designer played out his many lives, while also making a strong case that Lagerfeld’s impact on contemporary interior design is just as important, if not more so, than his influence on fashion.

In fact, when the first Lagerfeld interior was featured in a 1968 spread for L’OEil magazine, the editorial describes him merely as a “stylist”. The photographs of the apartment in an 18th-century mansion on rue de Université, show walls lined with plum-coloured rice paper, or lacquered deepest chocolate brown in sharp contrast to crisp, white low ceilings that accentuated the horizontality that was fashionable among the extremely fashionable at the time. Yet amid this setting of aggressively au courant modernism, the anachronistic pops of Art Nouveau and Art Deco objects foreshadow the young Karl’s innate gift for creating strikingly original environments whose harmony is achieved through the deft interplay of contrasting styles and contexts.

Lagerfeld learned early on that presenting himself in a succession of gem-like domestic settings was good for crafting his image. But Lagerfeld’s houses not only provided him with publicity, they also gave him an excuse to indulge in his greatest passion. Shopping!

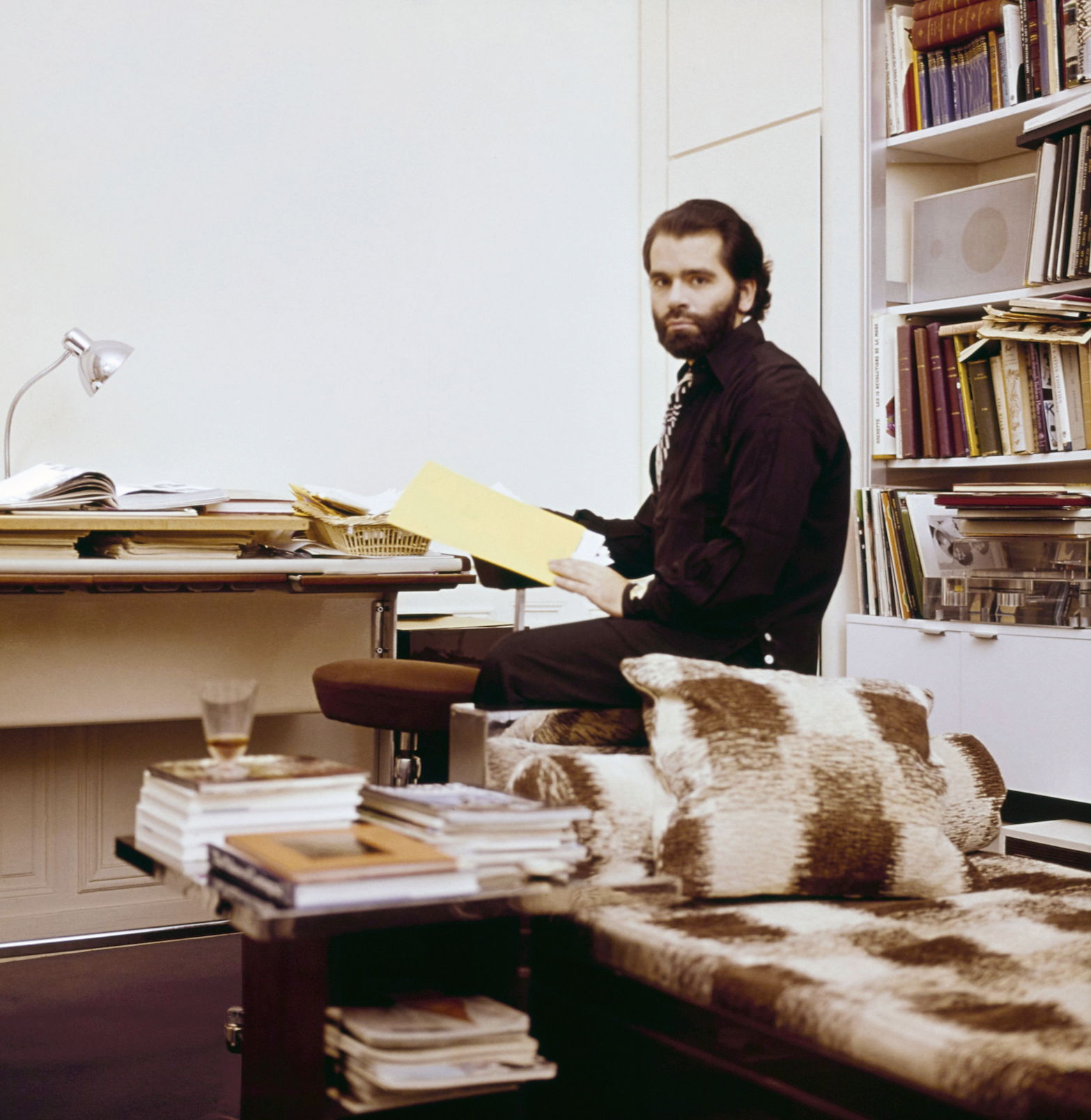

By 1973, Lagerfeld was living in a new apartment at Place Saint–Sulpice where his acquisition of important Art Deco treasures continued unabated. Now a bearded and muscular disco dandy, he could most often be found in the louche company of the models, starlets and assorted hedonistic beauties that gathered around the flamboyant fashion illustrator Antonio Lopez. Lagerfeld was also in the throes of a hopeless love affair with Jacques de Bascher whose favours he reluctantly shared with his nemesis Yves Saint Laurent.

He painted the rooms milky white and lined them with specially commissioned carpets—the tawny patterned striations of which invoked musky wild animal pelts. These lent a stark relief to the sleek, machine-age chrome lines of his Deco furnishings. To contemporary eyes it remains a strikingly original arrangement that subtly conveys the tensions at play in Lagerfeld’s own life: the cocaine fuelled orgies of his lover and friends, hosted in the pristine home of a man who claimed that “a bed is for one person”.

In 1975, a painful falling out with his beloved Jacques, who was descending into the abyss of addiction, saw almost his entire collection of peerless Art Deco furniture, paintings and objects put under the auctioneer’s hammer. This was the first of many auction sales, as he habitually shed the contents of his houses along with whatever incarnation of himself had lived there. Lagerfeld was dispassionate about parting with these precious goods. “It’s collecting that’s fun, not owning,” he said. And the reality for a collector on such a Renaissance scale, is that to continue buying, Lagerfeld had to sell.

Of all his residences, it was the 1977 purchase of Hôtel Pozzo di Borgo, a grand and beautifully preserved 18th-century house, that would finally allow him to fulfill his childhood fantasies of life in the court of Madame de Pompadour. And it was in this aura of Rococó splendour that the fashion designer began to affect, along with his tailored three-piece suits, a courtier’s ponytailed and powdered coif and a coquettish antique fan: marking the beginning of his transformation into a living, breathing global brand that even those with little interest in fashion would immediately recognise.

Lagerfeld’s increasing fame and financial success allowed him to indulge in an unprecedented spending frenzy, competing with deep-pocketed institutions like the Louvre to acquire the finest, most pedigreed pearls of the era—voluptuously carved and gilded bergères; ormolu chests; and fleshy, pastel-tinged Fragonard idylls—to adorn his urban palace. His one-time friend André Leon Talley described him in a contemporary article as suffering from “Versailles complex”.

However, in mid-1981, and in response to the election of left-wing president, François Mitterrand, Lagerfeld, with the assistance of his close friend Princess Caroline, became a resident of the tax haven of Monaco. He purchased two apartments on the 21st floor of Le Roccabella, a luxury residential block designed by Gio Ponti. One, in which he kept Jacques de Bascher, with whom he was now reconciled, was decorated in the strict, monochromatic Viennese Secessionist style that had long underpinned his aesthetic vocabulary; the other space, though, was something else entirely, cementing his notoriety as an iconoclastic tastemaker.

Lagerfeld had recently discovered the radically quirky designs of the Memphis Group led by Ettore Sottsass, and bought the collective’s entire first collection and had it shipped to Monaco. In a space with no right angles, these chaotically colourful, geometrically askew pieces—centred on Masanori Umeda’s famous boxing ring—gave visitors the disorientating sensation of having entered a corporeal comic strip. By 1991, the novelty of this jarring postmodern playhouse had inevitably worn thin and once again he sent it all to auction, later telling a journalist that “after a few years it was like living in an old Courrèges. Ha!”

In 1989, de Bascher died of an AIDS-related illness, and while Lagerfeld’s career continued to flourish, emotionally the famously stoic designer was struggling. In 2000, a somewhat corpulent Lagerfeld officially ended his “let them eat cake” years at the Hôtel Pozzo di Borgo, selling its sumptuous antique fittings in a massive headline auction that stretched over three days. As always there were other houses, but now with his longtime companion dead, and his celebrity metastasising making him a target for the paparazzi, he began to look less for exhibition spaces and more for private sanctuaries where he could pursue his endless, often lonely, work.

His next significant house was Villa Jako, named for his lost companion and built in the 1920s in a nouveau riche area of Hamburg close to where he grew up. Lagerfeld shot the advertising campaign for Lagerfeld Jako there—a fragrance created in memorial to de Bascher. The house featured a collection of mainly Scandinavian antiques, marking the aesthetic cusp between Art Nouveau and Art Deco. One of its rooms Lagerfeld decorated based on his remembrances of his childhood nursery. Here, he locked himself away to work—tellingly—on a series of illustrations for the fairy tale, The Emperor’s New Clothes. Villa Jako was a house of deep nostalgia and mourning.

But there were more acts—and more houses—to come in Lagerfeld’s life yet. In November 2000, upon seeing the attenuated tailoring of Hedi Slimane, then head of menswear at Christian Dior, the 135 kg Lagerfeld embarked on a strict dietary regime. Over the next 13 months, he melted into a shadow of his former self. It is this incarnation of Lagerfeld—high white starched collars; Slimane’s skintight suits, and fingerless leather gloves revealing hands bedecked with heavy silver rings—that is immediately recognisable some five years after his death.

The 200-year-old apartment in Quái Voltaire, Paris, was purchased in 2006, and after years of slumber Lagerfeld—a newly awakened Hip Van Winkle—was ready to remake it into his last modernist masterpiece. He designed a unique daylight simulation system that meant the monochromatic space was completely without shadows—and without memory. The walls were frosted and smoked glass, the floors concrete and silicone; and any hint of texture was banned with only shiny, sleek pieces by Marc Newson, Martin Szekely and the Bouroullec Brothers permitted. Few guests were allowed into this monastic environment where Lagerfeld worked, drank endless cans of Diet Coke and communed with Choupette, his beloved Birman cat, and parts of his collection of 300,000 books—one of the largest private collections in the world.

Lagerfeld died in 2019, and the process of dispersing his worldly goods is still ongoing. The Quái Voltaire apartment was sold this year for US$10.8 million (around $16.3 million). Now only the rue de Saint-Peres property remains within the Lagerfeld trust. Purchased after Quái Voltaire to further accommodate more of his books—35,000 were displayed in his studio alone, always stacked horizontally so he could read the titles without straining his neck—and as a place for food preparation as he loathed his primary living space having any trace of cooking smells. Today, the rue de Saint-Peres residence is open to the public as an arts performance space and most fittingly, a library.

You may also like.

By Josh Bozin

24/07/2024

Watch This Space: Mike Nouveau

Meet the game-changing horological influencers blazing a trail across social media—and doing things their own way.

In the thriving world of luxury watches, few people own a space that offers unfiltered digital amplification. And that’s precisely what makes the likes of Brynn Wallner, Teddy Baldassarre, Mike Nouveau and Justin Hast so compelling.

These thought-provoking digital crusaders are now paving the way for the story of watches to be told, and shown, in a new light. Speaking to thousands of followers on the daily—mainly via TikTok, Instagram and YouTube—these progressive commentators represent the new guard of watch pundits. And they’re swaying the opinions, and dollars, of the up-and-coming generations who now represent the target consumer of this booming sector.

—

MIKE NOUVEAU

Can we please see what’s on the wrist? That’s the question that catapulted Mike Nouveau into watch stardom, thanks to his penchant for highlighting incredibly rare timepieces across his TikTok account of more than 400,000 followers. When viewing Nouveau’s attention-grabbing video clips—usually shot in a New York City neighbourhood—it’s not uncommon to find him wrist-rolling some of the world’s rarest timepieces, like the million-dollar Cartier Cheich (a clip he posted in May).

But how did someone without any previous watch experience come to amass such a cult following, and in the process gain access to some of the world’s most coveted timepieces? Nouveau admits had been a collector for many years, but moved didn’t move into horology full-time until 2020, when he swapped his DJing career for one as a vintage watch specialist.

“I probably researched for a year before I even bought my first watch,” says Nouveau, alluding to his Rolex GMT Master “Pepsi” ref. 1675 from 1967, a lionised timepiece in the vintage cosmos. “I would see deals arise that I knew were very good, but they weren’t necessarily watches that I wanted to buy myself. I eventually started buying and selling, flipping just for fun because I knew how to spot a good deal.”

Nouveau claims that before launching his TikTok account in the wake of Covid-19, no one in the watch community knew he existed. “There really wasn’t much watch content, if any, on TikTok before I started posting, especially talking about vintage watches. There’s still not that many voices for vintage watches, period,” says Nouveau. “It just so happens that my audience probably skews younger, and I’d say there are just as many young people interested in vintage watches as there are in modern watches.”

View this post on Instagram

Nouveau recently posted a video to his TikTok account revealing that the average price of a watch purchased by Gen Z is now almost US$11,000 (around $16,500), with 41 percent of them coming into possession of a luxury watch in the past 12 months.

“Do as much independent research as you can [when buying],” he advises. “The more you do, the more informed you are and the less likely you are to make a mistake. And don’t bring modern watch expectations to the vintage world because it’s very different. People say, ‘buy the dealer’, but I don’t do that. I trust myself and myself only.”

—

Read more about the influencers shaking up horology here with Justin Hast, Brynn Wallner and Teddy Baldassare.

You may also like.

By Josh Bozin

24/07/2024

This Pristine 1960 Ferrari 250 Spider Could Fetch $24 Million at Auction

The car wears the same colours and has the same engine it left the factory with.

Some Ferraris are just a little bit more important than others.

Take, for example, the 1960 250 GT SWB California that RM Sotheby’s is auctioning off during this year’s Monterey Car Week. Any example of the open-top beauty would attract interest, but this one just so happens to be the first one that was built.

The 250 is one of the most legendary series of cars in Ferrari history. Between 1952 and 1964, the company released 21 different 250 models—seven for racetracks, 14 for public roads—of which the “Cali Spider” might be the most well regarded, thanks to its potent V-12 and a Pininfarina-penned design that is one of the most beautiful bodies to grace an automobile. The roadster, which was specifically built for the U.S., made its debut in 1957 as a long-wheel-base model (LWB), but it wasn’t until the SWB model debut in 1960 that it became clear how special it was. This example isn’t just the first to roll off the line. It’s the actual car that was used to introduce the world to the model at the 1960 Geneva Motor Show.

Just 56 examples of the 250 GT SWB California Spider would be built by Scaglietti during the three years it was in production. The first of those, chassis 1795 GT, is finished in a glossy coat of Grigio. The two-door had a red leather interior at Geneva but was returned to the factory and re-outfitted with black leather upholstery before being delivered to its original owner, British race car driver John Gordon Bennet. Six-and-a-half decades later the car looks identical to how it did when it left the factory the second time.

In addition to its original bodywork, the chassis 1795 GT features its original engine, gearbox, and rear axle. That mill is the competition-spec Tipo 168, a 3.0-litre V-12 that makes 196.1 kW. That may not sound like much by today’s standards, but, when you consider that the 250 GT SWB California Spider tips the scales around 952 kilograms, it’s more than enough.

The first 250 GT SWB California Spider is scheduled to go up for bid during RM Sotheby’s annual Monterey Car Week auction, which runs from Thursday, August 15, to Saturday, August 17. Unsurprisingly, the house has quite high hopes for the car. The car carries an estimate of between $24 million and $26 million, which could make it one of the most expensive cars ever sold at auction.

You may also like.

By Josh Bozin

24/07/2024