How 3 Of Italy’s Master Tailors Are Making Suits Easier To Wear

The tastemakers behind Corneliani, Isaia and Caruso share how their new breed of tailoring fits the way we dress now.

Related articles

For the past five or six years—but especially during the last two—menswear writers around the globe have been either balefully lamenting or gleefully exclaiming, depending on their personal tastes, the demise of the suit.

And indeed, for a time, it looked like the suit might have been on the way out, with brands including Brooks Brothers in the US and Kilgour and Gieves & Hawkes in the UK declaring bankruptcy or entering liquidation in the wake of lockdowns and empty offices.

Around the globe, yes, but in Italy, not so much. According to an admittedly unscientific survey of a few stylish Italian friends, far fewer column inches have been penned there on the subject. Italian tailoring has fared better than elsewhere, perhaps because it’s a different kind of animal: softer and less formal than its Parisian and English counterparts, more lightly constructed and relaxed in attitude than its American cousins. So the Italian sensibility is better primed to adapt more naturally to what is required right now. But possibly, too, because Italian men tend to wear tailored clothing differently—more casually, with an extra shirt button (or two) undone, with jackets unfastened, with loafers. Not just for work. For whenever they want to feel, and look, their best. You’ll often see older Italian men meeting up in town squares wearing tailoring that has clearly been worn for many years and still looks great.

So what can the stylish man, and indeed the style industry, learn from the Italians? We spoke to three of Italy’s biggest sartorial players—Corneliani, Isaia and Caruso—to find out. With close to a year of normal life behind them, this trio has found a post-pandemic-shutdown stride. All three make their clothing in their own dedicated tailoring factories and have evolved their offerings in interesting ways. What, then, do they believe menswear should look like in the post-business-suit era of 2022 and beyond?

To answer this question, Corneliani got creative. The label introduced a new, experimental sub-brand called Corneliani Circle for the autumn/winter 2020 season, just before the pandemic struck. Designed with “a forward-looking approach,” the resulting capsule collection—which featured distinctive pieces such as organic-cotton field jackets and blazer-meets-chore-coat hybrids—marked a step change for a company that has historically relied on traditional suiting. At the start of this year, Corneliani Circle was granted its own dedicated design lead, Paul Surridge, a Briton who was formerly the creative director of Roberto Cavalli. Billed as a collaboration with the new label, Surridge’s role is to “rejuvenate” Corneliani’s classicism and use the Circle collection to set a new, relevant direction. What does “rejuvenating” classic tailoring mean to him? Interviews have been lightly edited and condensed for clarity.

Paul, you started to collaborate with Corneliani on Corneliani Circle in January. What were you thinking after two years of pandemic disruption?

PS: For me, that period was almost a complete reduction of taste, a reduction of style. We were just left with comfort—that was all that mattered. Consumers were bombarded with images of A-list celebrities and style icons in slouchy home attire. The glitz and glamour of the red carpet disappeared. Also, I don’t think the [pandemic] killed [streetwear], but it was already saturated, oversaturated, because it was in everyone’s lives.

Softer, slouchier silhouettes in elegant neutrals, such as this ensemble in monochromatic beige, give a fashion-forward refresh to Corneliani’s classic suiting. Courtesy of Corneliani

How has this filtered into your new vision for Corneliani Circle?

PS: I looked at Corneliani and felt that [the Circle capsule] was an opportunity to rejuvenate tailoring and attract a more fashion-forward demographic by using comfort to do something very elegant.

And what does good taste mean to you?

PS: This whole idea of “radical chic.”

I like “radical chic.” Are you talking about the term Tom Wolfe coined with reference to liberals dressing like radicals?

PS: Yes, I heard the term from a close friend and CEO of a luxury brand when we were discussing design and luxury today. The “radical” works for me because I wanted to be a bit more provocative with the idea of tailoring for Corneliani. For me, this project is about how far I can push the envelope, while being relevant to the brand. The “chic” component is in the colours we used, which are very familiar but put into a differ- ent context. Beautiful earthy tones and sophisticated shades—I find them quite peaceful.

Surridge’s first capsule collection, which will be available next spring, epitomizes this idea. The items are more generous and slouchier than Corneliani’s clean-cut mainline suiting, with a washed-out colour palette and a focus on easy mix-and-match pieces. It’s a very different approach for the brand but still understated and composed. Take, for example, the collection’s Architect jacket, which references a straitlaced British look, with square proportions and a three-button front. Despite its classic roots, the jacket in Surridge’s hands is a subversive piece for customers “with a younger mindset,” distinctive in its silhouette and construction.

PS: It’s an oversized, upscaled blazer. We cut it in wool, hemp and silk, which I was worried might feel a bit [old-school], but by underpinning it with a white T-shirt, a tailored pant and then a long belt, it felt contemporary—like we’d tipped something very traditional into a modern key.

Do you think that modern tailoring still has a place in a man’s wardrobe today?

PS: Totally, it never goes away. The male wardrobe is defined by the shoulder. The shoulder expresses the times.

So, what are your shoulder lines saying about the future of men’s style?

PS: For tailoring to work it has to reflect the mood, so it has to be comfortable. It has to be loose; it can’t be fitted. It has to be soft. The shoulder has to be lightly constructed, and the jacket’s collar has to sit around the neck like a scarf. When you combine these things with the silhouette we worked on, with the jacket longer in the front and the shoulder seams thrown towards the back, you end up with a slightly sportier, easier feel. These aren’t clothes for a suited-and-booted investment banker in a boardroom.

Is the business suit on its way out, then?

PS: I think the idea of a uniform, of “institutional dressing,” is gone. The corporate suit will still exist because some professionals will always need to wear one, but in a world where most of us don’t need to wear suits, we have an opportunity to remove tailoring’s formal aspect and put it into an informal context, which I think is very fresh.

If Corneliani Circle’s new direction is all about quiet, contemporary elegance, at colourful Neapolitan brand Isaia, CEO Gianluca Isaia, representing the third generation of family ownership, has taken a different tack. Isaia has moved quickly to pivot its in-house production, supplementing flamboyant suiting with casual sportswear and all the pieces a man needs to dress down his suits and sport coats. In the first half of 2022, sportswear accounted for 40 per cent of sales, twice what it was going into the pandemic. Dialling in from a break on Capri, Isaia talked about this new strategy and how he’s elevating sportswear with a tailored sensibility.

GI: In 2019, the company was growing in a healthy way—we’d had double-digit growth every year for the past four or five years. Then Covid hit and we had a huge shock, because our sales were mostly concentrated in jackets, suits, dress shirts and ties. Perhaps only 20 per cent of our sales was sportswear.

That sounds challenging. How quickly were you able to respond to that, and what did you do?

GI: Even in the first lockdown, we started to plan a new strategy. Over the last two years we’ve internalized most of the production of casualwear categories that in 2019 we were making with external factories. Our own factory started to produce pajamas, robes, polo shirts and jersey pieces. If nothing else, we had to keep all our makers busy, because there was no need to make any of our tailoring.

These trousers’ double-button waist tab and kissing pleats are among the sartorial details that ground Isaia’s more irreverent designs in the Neapolitan tailoring tradition. Courtesy of Isaia

You clearly recognized the need to respond to the pandemic by creating casualwear. But how do you think the pandemic has changed men’s style long-term?

GI: Men won’t go back in terms of comfort. Take, for example, the classic pant. We are selling more drawstring pants to wear under blazers than we ever have before, even in classic tailoring fabrics. Men’s shoes are different, too—men want more comfortable shoes. Honestly, today, I don’t know if we’ll ever go back to wearing ties.

So luxury sportswear is a growth area for Isaia, then? Is that customer any different from your tailoring one?

GI: Our customer can tell if a buttonhole is sewn by hand or not, and he can recognize hand-stitching, whether it’s in a jacket or a jersey polo. Certainly, our jersey is selling extremely well. We buy the fabrics from the best Italian mills, in cashmere-silk or cotton-silk, and cashmere-cotton blends.

But tailoring is still a significant part of your sales, so how are your customers combining suiting and sportswear?

GI: Let’s say a mix between tailored pieces and sportswear [simultaneously] that feels very fluid. Certainly, that’s what we now stand for as a brand.

Back in the north of Italy, in the town of Soragna, Caruso’s 420-strong tailoring workshop is struggling to keep up with renewed demand. “Production-wise, many brands thought the jacket was dead, and they shut down their own production. Now they’re coming to us,” says CEO Marco Angeloni, who joined the company in 2019 and has steered the ship through the pandemic’s choppy waters. Angeloni’s take on menswear is subtler than that of Surridge and Isaia. Caruso’s collections aren’t as flamboyant as Isaia’s, nor as fashion-led as Corneliani Circle’s. Instead, Angeloni is seeing his customers embrace “playful elegance” and a revived interest in the classics, including statement eveningwear.

Let’s get the obvious question out of the way at the start. How has the pandemic changed menswear for you, and for Caruso?

MA: When it arrived, everyone’s motto was: “The jacket is over. You don’t need a jacket for a video conference.” I think that was true for four or five months.

Now I really believe there’s a desire for a man to, first of all, enjoy life more, and to find pleasure in dressing up again. For sure, this isn’t a comeback of the uniform.

The uniform is something that, in my opinion, was already dead before the pandemic. The pandemic hit it really hard. Now the jacket is coming back because it’s an object of desire. All of a sudden, it’s a way of being chic again. I think we’re seeing something more playful but still elegant coming back.

What does that mean to you? What makes a jacket an object of desire?

MA: It means that we are talking to a man who wants to dress in a way that shows that his clothes are his own choice, not his boss’s choice. Last season, sales were 68 per cent up, which for us is a gigantic comeback. But if I look at the colours, before the pandemic it used to be 80 per cent blue, perhaps 16 per cent grey and then a touch of something else. Now it’s not all about blue. We’re seeing more natural colours sell, like camel, shades of green—something that shows you have taste.

Caruso’s fall/winter ’22 collection, inspired by perennial style muse Miles Davis, is awash in earthy colours and luxurious separates. And as Isaia mentioned, there’s not a tie in sight. Instead, sleek knitwear underpins tonal tailoring, and there’s a surprising focus on standout tuxedos, whether in bright brown silk-wool or bold silk-wool jacquard. Looking ahead to spring 2023, Caruso has developed several new qualities of seersucker in superfine tropical wool, in green, camel and other contemporary colours, challenging the fabric’s stuffy blue-and-white-striped stereotype. But, if Caruso’s styling and fabrications are evolving, the brand’s two oldest and most classic jacket models have quickly bounced back.

Caruso is combining sportswear and soft tailoring for a modern take on the male wardrobe, as with this lightly padded Ponza jacket and wool-cashmere hoodie. Courtesy of Caruso

MA: During the pandemic, we introduced a technical jacket called Ponza, entirely made from Japanese nylon. It sold very well back then. Now I see this is already decreasing because, all of a sudden, people are asking for suits.

So technical, “novelty” tailoring had its moment in the pandemic, but actually that moment has passed?

MA: Yes. Now the Aida jacket [Caruso’s signature tailored jacket] is our best-selling item, a classic jacket in which there’s no shoulder pad whatsoever, just the canvas that runs up into the shoulder. If you look at the category of suits and jackets, the Aida will be almost 50 percent of sales—it’s really strong.

At the same time, we’re seeing an item which we thought was dead, our Norma jacket, which is more constructed, is coming back. I’m not sure whether it’s a fashion statement, or a reaction to hoodies and sweatshirts with no shoulder to them, but there’s a trend coming back there.

So, in 2022, the traditional business suit is on the rocks, and expressive “lifestyle” tailoring to socialize in is on the upswing. But if comfort was menswear’s buzzword in 2021, today the concept is combining with newfound sartorial freedoms and the desire, as Angeloni emphasizes, to play with the traditional uniform and still be elegant.

While the pandemic dealt many suiting brands a heavy blow, it has also helped some tailoring houses—Isaia, Caruso and Corneliani among them—break new ground and rethink what matters to their clients. Gianluca Isaia’s own personal definition of elegance speaks to this shift in perspective:

GI: I don’t think the concept of elegance has changed from before Covid. Elegance is something really personal. I always give this example: You have to imagine yourself on a stage alone with a lot of people in front of you. If you feel comfortable with what you’re wearing, you can be elegant anywhere.

What makes a man elegant in 2022, then?

GI: What has changed is the old concept of the rules: “The shirt has to be like this, the length of the jacket has to be like that.” Now we help our customers to find their own rules to be comfortable, and so to be elegant.”

Subscribe to the Newsletter

Recommended for you

Ode to Oasi

Ermenegildo Zegna wrote the book on dapper Italian style. Now, a new coffee-table tome pays homage to its greatest creation—one that, hopefully, will endure long after the brand is gone.

By Brad Nash

June 25, 2024

Everybody Loves Naomi

Fashion fans adore her. And so do we. Lucky, then, that a new exhibition is paying homage to the undisputed queen of the catwalk.

By Joseph Tenni

June 22, 2024

You may also like.

By Josh Bozin

24/07/2024

You may also like.

5 Lounge Chairs That Add Chic Seating to Your Space

Daybeds, the most relaxed of seating solutions, offer a surprising amount of utility.

Chaise longue, daybed, recamier, duchesse brisée—elongated furniture designed for relaxing has a roster of fancy names. While the French royal court of Louis XIV brought such pieces to prominence in fashionable European homes, the general idea has been around far longer: The Egyptian pharaohs were big fans, while daybeds from China’s Ming dynasty spurred all those Hollywood Regency fretwork pieces that still populate Palm Beach living rooms. Even Mies van der Rohe, one of design’s modernist icons, got into the lounge game with his Barcelona couch, a study of line and form that holds up today.

But don’t get caught up in who invented them, or what to call them. Instead, consider their versatility: Backless models are ideal in front of large expanses of glass (imagine lazing on one with an ocean view) or at the foot of a bed, while more structured pieces can transform any corner into a cozy reading nook. Daybeds may be inextricably linked to relaxation, but from a design perspective, they put in serious work.

Emmy, Egg Collective

In designing the Emmy chaise, the Egg Collective trio of Stephanie Beamer, Crystal Ellis and Hillary Petrie, who met as students at Washington University in St. Louis, aimed for versatility. Indeed, the tailored chaise looks equally at home in a glass skyscraper as it does in a turn-of-the-century town house. Combining the elegance of a smooth, solid oak or walnut frame with the comfort of bolsters and cushioned upholstery or leather, it works just as well against a wall or at the heart of a room. From around $7,015; Eggcollective.com

Plum, Michael Robbins

Plum, Michael Robbins

Woodworker Michael Robbins is the quintessential artisan from New York State’s Hudson Valley in that both his materials and methods pay homage to the area. In fact, he describes his style as “honest, playful, elegant and reflective of the aesthetic of the Hudson Valley surroundings”. Robbins crafts his furniture by hand but allows the wood he uses to help guide the look of a piece. (The studio offers eight standard finishes.) The Plum daybed, brought to life at Robbins’s workshop, exhibits his signature modern rusticity injected with a hint of whimsy thanks to the simplicity of its geometric forms. Around $4,275; MichaelRobbins.com

Kimani, Reda Amalou Design

French architect and designer Reda Amalou acknowledges the challenge of creating standout seating given the number of iconic 20th-century examples already in existence. Still, he persists—and prevails. The Kimani, a bent slash of a daybed in a limited edition of eight pieces, makes a forceful statement. Its leather cushion features a rolled headrest and rhythmic channel stitching reminiscent of that found on the seats of ’70s cars; visually, these elements anchor the slender silhouette atop a patinated bronze base with a sure-handed single line. The result: a seamless contour for the body. Around $33,530; RedaAmalou

Dune, Workshop/APD

From a firm known for crafting subtle but luxurious architecture and interiors, Workshop/APD’s debut furniture collection is on point. Among its offerings is the leather-wrapped Dune daybed. With classical and Art Deco influences, its cylindrical bolsters are a tactile celebration, and the peek of the curved satin-brass base makes for a sensual surprise. Associate principal Andrew Kline notes that the daybed adeptly bridges two seating areas in a roomy living space or can sit, bench-style, at the foot of a bed. From $13,040; Workshop/ APD

Sherazade, Edra

Designed by Francesco Binfaré, this sculptural, minimalist daybed—inspired by the rugs used by Eastern civilizations—allows for complete relaxation. Strength combined with comfort is the name of the game here. The Sherazade’s structure is made from light but sturdy honeycomb wood, while next-gen Gellyfoam and synthetic wadding aid repose. True to Edra’s amorphous design codes, it can switch configurations depending on the user’s mood or needs; for example, the accompanying extra pillows—one rectangular and one cylinder shaped— interchange to become armrests or backrests. From $32,900; Edra

You may also like.

By Josh Bozin

24/07/2024

22/07/2024

Watches & Wonders 2024 Showcase: Hermès

We head to Geneva for the Watches & Wonders exhibition; a week-long horological blockbuster featuring the hottest new drops, and no shortage of hype.

With Watches & Wonders 2024 well and truly behind us, we review some of the novelties Hermès presented at this year’s event.

—

HERMÈS

Moving away from the block colours and sporty aesthetic that has defined Hermès watches in recent years, the biggest news from the French luxury goods company at Watches & Wonders came with the unveiling of its newest collection, the Hermès Cut.

It flaunts a round bezel, but the case middle is nearer to a tonneau shape—a relatively simple design that, despite attracting flak from some watch aficionados, works. While marketed as a “women’s watch”, the Cut has universal appeal thanks to its elegant package and proportions. It moves away from the Maison’s penchant for a style-first product; it’s a watch that tells the time, not a fashion accessory with the ability to tell the time.

Hermès gets the proportions just right thanks to a satin-brushed and polished 36 mm case, PVD-treated Arabic numerals, and clean-cut edges that further accentuate its character. One of the key design elements is the positioning of the crown, boldly sitting at half-past one and embellished with a lacquered or engraved “H”, clearly stamping its originality. The watch is powered by a Hermès Manufacture movement H1912, revealed through its sapphire crystal caseback. In addition to its seamlessly integrated and easy-wearing metal bracelet, the Cut also comes with the option for a range of coloured rubber straps. Together with its clever interchangeable system, it’s a cinch to swap out its look.

It will be interesting to see how the Hermès Cut fares in coming months, particularly as it tries to establish its own identity separate from the more aggressive, but widely popular, Ho8 collection. Either way, the company is now a serious part of the dialogue around the concept of time.

—

Read more about this year’s Watches & Wonders exhibition at robbreport.com.au

You may also like.

22/07/2024

Living La Vida Lagerfeld

The world remembers him for fashion. But as a new tome reveals, the iconoclastic designer is defined as much by extravagant, often fantastical, homes as he is clothes.

“Lives, like novels, are made up of chapters”, the world-renowned bibliophile, Karl Lagerfeld, once observed.

Were a psychological-style novel ever to be written about Karl Lagerfeld’s life, it would no doubt give less narrative weight to the story of his reinvigoration of staid fashion houses like Chloe, Fendi and Chanel than to the underpinning leitmotif of the designer’s constant reinvention of himself.

In a lifetime spanning two centuries, Lagerfeld made and dropped an ever-changing parade of close friends, muses, collaborators and ambiguous lovers, as easily as he changed his clothes, his furniture… even his body. Each chapter of this book would be set against the backdrop of one of his series of apartments, houses and villas, whose often wildly divergent but always ultra-luxurious décor reflected the ever-evolving personas of this compulsively public but ultimately enigmatic man.

With the publication of Karl Lagerfeld: A Life in Houses these wildly disparate but always exquisite interiors are presented for the first time together as a chronological body of work. The book indeed serves as a kind of visual novel, documenting the domestic dreamscapes in which the iconic designer played out his many lives, while also making a strong case that Lagerfeld’s impact on contemporary interior design is just as important, if not more so, than his influence on fashion.

In fact, when the first Lagerfeld interior was featured in a 1968 spread for L’OEil magazine, the editorial describes him merely as a “stylist”. The photographs of the apartment in an 18th-century mansion on rue de Université, show walls lined with plum-coloured rice paper, or lacquered deepest chocolate brown in sharp contrast to crisp, white low ceilings that accentuated the horizontality that was fashionable among the extremely fashionable at the time. Yet amid this setting of aggressively au courant modernism, the anachronistic pops of Art Nouveau and Art Deco objects foreshadow the young Karl’s innate gift for creating strikingly original environments whose harmony is achieved through the deft interplay of contrasting styles and contexts.

Lagerfeld learned early on that presenting himself in a succession of gem-like domestic settings was good for crafting his image. But Lagerfeld’s houses not only provided him with publicity, they also gave him an excuse to indulge in his greatest passion. Shopping!

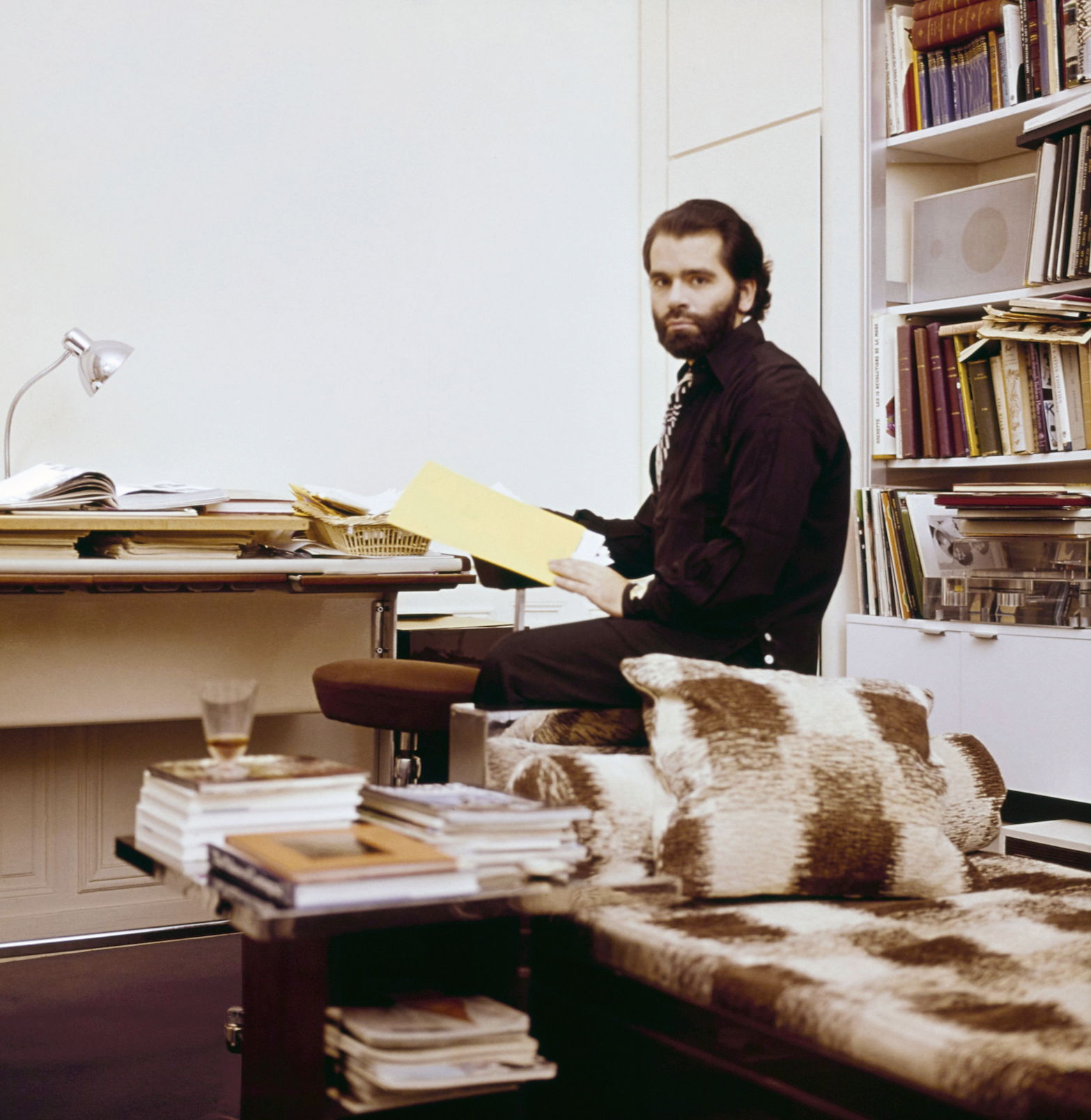

By 1973, Lagerfeld was living in a new apartment at Place Saint–Sulpice where his acquisition of important Art Deco treasures continued unabated. Now a bearded and muscular disco dandy, he could most often be found in the louche company of the models, starlets and assorted hedonistic beauties that gathered around the flamboyant fashion illustrator Antonio Lopez. Lagerfeld was also in the throes of a hopeless love affair with Jacques de Bascher whose favours he reluctantly shared with his nemesis Yves Saint Laurent.

He painted the rooms milky white and lined them with specially commissioned carpets—the tawny patterned striations of which invoked musky wild animal pelts. These lent a stark relief to the sleek, machine-age chrome lines of his Deco furnishings. To contemporary eyes it remains a strikingly original arrangement that subtly conveys the tensions at play in Lagerfeld’s own life: the cocaine fuelled orgies of his lover and friends, hosted in the pristine home of a man who claimed that “a bed is for one person”.

In 1975, a painful falling out with his beloved Jacques, who was descending into the abyss of addiction, saw almost his entire collection of peerless Art Deco furniture, paintings and objects put under the auctioneer’s hammer. This was the first of many auction sales, as he habitually shed the contents of his houses along with whatever incarnation of himself had lived there. Lagerfeld was dispassionate about parting with these precious goods. “It’s collecting that’s fun, not owning,” he said. And the reality for a collector on such a Renaissance scale, is that to continue buying, Lagerfeld had to sell.

Of all his residences, it was the 1977 purchase of Hôtel Pozzo di Borgo, a grand and beautifully preserved 18th-century house, that would finally allow him to fulfill his childhood fantasies of life in the court of Madame de Pompadour. And it was in this aura of Rococó splendour that the fashion designer began to affect, along with his tailored three-piece suits, a courtier’s ponytailed and powdered coif and a coquettish antique fan: marking the beginning of his transformation into a living, breathing global brand that even those with little interest in fashion would immediately recognise.

Lagerfeld’s increasing fame and financial success allowed him to indulge in an unprecedented spending frenzy, competing with deep-pocketed institutions like the Louvre to acquire the finest, most pedigreed pearls of the era—voluptuously carved and gilded bergères; ormolu chests; and fleshy, pastel-tinged Fragonard idylls—to adorn his urban palace. His one-time friend André Leon Talley described him in a contemporary article as suffering from “Versailles complex”.

However, in mid-1981, and in response to the election of left-wing president, François Mitterrand, Lagerfeld, with the assistance of his close friend Princess Caroline, became a resident of the tax haven of Monaco. He purchased two apartments on the 21st floor of Le Roccabella, a luxury residential block designed by Gio Ponti. One, in which he kept Jacques de Bascher, with whom he was now reconciled, was decorated in the strict, monochromatic Viennese Secessionist style that had long underpinned his aesthetic vocabulary; the other space, though, was something else entirely, cementing his notoriety as an iconoclastic tastemaker.

Lagerfeld had recently discovered the radically quirky designs of the Memphis Group led by Ettore Sottsass, and bought the collective’s entire first collection and had it shipped to Monaco. In a space with no right angles, these chaotically colourful, geometrically askew pieces—centred on Masanori Umeda’s famous boxing ring—gave visitors the disorientating sensation of having entered a corporeal comic strip. By 1991, the novelty of this jarring postmodern playhouse had inevitably worn thin and once again he sent it all to auction, later telling a journalist that “after a few years it was like living in an old Courrèges. Ha!”

In 1989, de Bascher died of an AIDS-related illness, and while Lagerfeld’s career continued to flourish, emotionally the famously stoic designer was struggling. In 2000, a somewhat corpulent Lagerfeld officially ended his “let them eat cake” years at the Hôtel Pozzo di Borgo, selling its sumptuous antique fittings in a massive headline auction that stretched over three days. As always there were other houses, but now with his longtime companion dead, and his celebrity metastasising making him a target for the paparazzi, he began to look less for exhibition spaces and more for private sanctuaries where he could pursue his endless, often lonely, work.

His next significant house was Villa Jako, named for his lost companion and built in the 1920s in a nouveau riche area of Hamburg close to where he grew up. Lagerfeld shot the advertising campaign for Lagerfeld Jako there—a fragrance created in memorial to de Bascher. The house featured a collection of mainly Scandinavian antiques, marking the aesthetic cusp between Art Nouveau and Art Deco. One of its rooms Lagerfeld decorated based on his remembrances of his childhood nursery. Here, he locked himself away to work—tellingly—on a series of illustrations for the fairy tale, The Emperor’s New Clothes. Villa Jako was a house of deep nostalgia and mourning.

But there were more acts—and more houses—to come in Lagerfeld’s life yet. In November 2000, upon seeing the attenuated tailoring of Hedi Slimane, then head of menswear at Christian Dior, the 135 kg Lagerfeld embarked on a strict dietary regime. Over the next 13 months, he melted into a shadow of his former self. It is this incarnation of Lagerfeld—high white starched collars; Slimane’s skintight suits, and fingerless leather gloves revealing hands bedecked with heavy silver rings—that is immediately recognisable some five years after his death.

The 200-year-old apartment in Quái Voltaire, Paris, was purchased in 2006, and after years of slumber Lagerfeld—a newly awakened Hip Van Winkle—was ready to remake it into his last modernist masterpiece. He designed a unique daylight simulation system that meant the monochromatic space was completely without shadows—and without memory. The walls were frosted and smoked glass, the floors concrete and silicone; and any hint of texture was banned with only shiny, sleek pieces by Marc Newson, Martin Szekely and the Bouroullec Brothers permitted. Few guests were allowed into this monastic environment where Lagerfeld worked, drank endless cans of Diet Coke and communed with Choupette, his beloved Birman cat, and parts of his collection of 300,000 books—one of the largest private collections in the world.

Lagerfeld died in 2019, and the process of dispersing his worldly goods is still ongoing. The Quái Voltaire apartment was sold this year for US$10.8 million (around $16.3 million). Now only the rue de Saint-Peres property remains within the Lagerfeld trust. Purchased after Quái Voltaire to further accommodate more of his books—35,000 were displayed in his studio alone, always stacked horizontally so he could read the titles without straining his neck—and as a place for food preparation as he loathed his primary living space having any trace of cooking smells. Today, the rue de Saint-Peres residence is open to the public as an arts performance space and most fittingly, a library.

You may also like.

By Josh Bozin

24/07/2024

Watch This Space: Mike Nouveau

Meet the game-changing horological influencers blazing a trail across social media—and doing things their own way.

In the thriving world of luxury watches, few people own a space that offers unfiltered digital amplification. And that’s precisely what makes the likes of Brynn Wallner, Teddy Baldassarre, Mike Nouveau and Justin Hast so compelling.

These thought-provoking digital crusaders are now paving the way for the story of watches to be told, and shown, in a new light. Speaking to thousands of followers on the daily—mainly via TikTok, Instagram and YouTube—these progressive commentators represent the new guard of watch pundits. And they’re swaying the opinions, and dollars, of the up-and-coming generations who now represent the target consumer of this booming sector.

—

MIKE NOUVEAU

Can we please see what’s on the wrist? That’s the question that catapulted Mike Nouveau into watch stardom, thanks to his penchant for highlighting incredibly rare timepieces across his TikTok account of more than 400,000 followers. When viewing Nouveau’s attention-grabbing video clips—usually shot in a New York City neighbourhood—it’s not uncommon to find him wrist-rolling some of the world’s rarest timepieces, like the million-dollar Cartier Cheich (a clip he posted in May).

But how did someone without any previous watch experience come to amass such a cult following, and in the process gain access to some of the world’s most coveted timepieces? Nouveau admits had been a collector for many years, but moved didn’t move into horology full-time until 2020, when he swapped his DJing career for one as a vintage watch specialist.

“I probably researched for a year before I even bought my first watch,” says Nouveau, alluding to his Rolex GMT Master “Pepsi” ref. 1675 from 1967, a lionised timepiece in the vintage cosmos. “I would see deals arise that I knew were very good, but they weren’t necessarily watches that I wanted to buy myself. I eventually started buying and selling, flipping just for fun because I knew how to spot a good deal.”

Nouveau claims that before launching his TikTok account in the wake of Covid-19, no one in the watch community knew he existed. “There really wasn’t much watch content, if any, on TikTok before I started posting, especially talking about vintage watches. There’s still not that many voices for vintage watches, period,” says Nouveau. “It just so happens that my audience probably skews younger, and I’d say there are just as many young people interested in vintage watches as there are in modern watches.”

View this post on Instagram

Nouveau recently posted a video to his TikTok account revealing that the average price of a watch purchased by Gen Z is now almost US$11,000 (around $16,500), with 41 percent of them coming into possession of a luxury watch in the past 12 months.

“Do as much independent research as you can [when buying],” he advises. “The more you do, the more informed you are and the less likely you are to make a mistake. And don’t bring modern watch expectations to the vintage world because it’s very different. People say, ‘buy the dealer’, but I don’t do that. I trust myself and myself only.”

—

Read more about the influencers shaking up horology here with Justin Hast, Brynn Wallner and Teddy Baldassare.

You may also like.

By Josh Bozin

24/07/2024

This Pristine 1960 Ferrari 250 Spider Could Fetch $24 Million at Auction

The car wears the same colours and has the same engine it left the factory with.

Some Ferraris are just a little bit more important than others.

Take, for example, the 1960 250 GT SWB California that RM Sotheby’s is auctioning off during this year’s Monterey Car Week. Any example of the open-top beauty would attract interest, but this one just so happens to be the first one that was built.

The 250 is one of the most legendary series of cars in Ferrari history. Between 1952 and 1964, the company released 21 different 250 models—seven for racetracks, 14 for public roads—of which the “Cali Spider” might be the most well regarded, thanks to its potent V-12 and a Pininfarina-penned design that is one of the most beautiful bodies to grace an automobile. The roadster, which was specifically built for the U.S., made its debut in 1957 as a long-wheel-base model (LWB), but it wasn’t until the SWB model debut in 1960 that it became clear how special it was. This example isn’t just the first to roll off the line. It’s the actual car that was used to introduce the world to the model at the 1960 Geneva Motor Show.

Just 56 examples of the 250 GT SWB California Spider would be built by Scaglietti during the three years it was in production. The first of those, chassis 1795 GT, is finished in a glossy coat of Grigio. The two-door had a red leather interior at Geneva but was returned to the factory and re-outfitted with black leather upholstery before being delivered to its original owner, British race car driver John Gordon Bennet. Six-and-a-half decades later the car looks identical to how it did when it left the factory the second time.

In addition to its original bodywork, the chassis 1795 GT features its original engine, gearbox, and rear axle. That mill is the competition-spec Tipo 168, a 3.0-litre V-12 that makes 196.1 kW. That may not sound like much by today’s standards, but, when you consider that the 250 GT SWB California Spider tips the scales around 952 kilograms, it’s more than enough.

The first 250 GT SWB California Spider is scheduled to go up for bid during RM Sotheby’s annual Monterey Car Week auction, which runs from Thursday, August 15, to Saturday, August 17. Unsurprisingly, the house has quite high hopes for the car. The car carries an estimate of between $24 million and $26 million, which could make it one of the most expensive cars ever sold at auction.

You may also like.

By Josh Bozin

24/07/2024