The 25 Greatest Supercars Of The 21st Century (So Far)

From the Bugatti Veyron to the Pagani Utopia, this is our revised list of the very best models from the new millennium…at least for now.

Related articles

There is no denying that the landscape of the automotive industry is seismically shifting. Advances in autonomous driving, ubiquitous ride-sharing platforms and even new app-driven models for ownership, while convenient, do not nurture a love for the automobile or contribute to any semblance of car culture.

Yet it would be a mistake to assume that younger generations are becoming unilaterally apathetic. How could they? We are at a confluence of tech and tradition, analog and artificial intelligence and nowhere is this more evident than with the current ultra-high-performance machines on the market.

To that end, we’ve updated our list of the 25 greatest supercars so far this century, and it’s by all means an exercise in subjectivity. Some models that made it here may not be the fastest production cars out there or the most agile, but they have either fuelled our imagination or introduced new levels of innovation. And honestly, in some cases, they’re just the ones our inner child feels compelled to draw . . . all the time. And the fact that these will all become the classics of the future has us confident that when it comes to the life automotive, the kids are going to be just fine.

McLaren F1

Ok, so the first one on this list is technically from the last century, the 1990s to be exact, but it’s here as a benchmark and baseline for the models that follow. A top speed of 371 km/h. Back in 1992, no other production car had ever gone that fast. It was mind-blowing. But that’s what the McLaren F1 did; blow minds. With its feather-weight carbon-fiber chassis, single-minded focus on shaving weight and a bespoke six-litre, 627 hp BMW V-12 for power, it could sear to 100 km/h in just 3.2 seconds.

Costing nearly $1 million at launch, it was also mind-blowingly expensive. Today, however, in the rare chance that one of the 106 examples comes to market, expect to pay around $20 million. The ultimate supercar? Some would say there’s no question. Howard Walker

Bugatti Veyron Super Sport

Bugatti stormed back to the modern age from the pages of automotive history with the 2005 Veyron, which announced its intentions with quad-turbo twin-V8s that made an astonishing 1,200 hp. Fast forward a half-decade, and the Super Sport version of the Veyron promptly claimed the Guinness Book of Records title in 2010 as world’s fastest production car with a 418 km/h run at Volkswagen’s Wolfsburg test track.

The Veyron Super Sport has been eclipsed by the 1,500 hp Bugatti Chiron Super Sport which, driven by Andy Wallace, hit 489 km/h in testing in 2019. However, nobody is apt to forget the Veyron—the machine that made the modern version of Bugatti what it is today. Marco della Cava

Ferrari LaFerrari

2013 was an auspicious year for supercars, with no fewer than three major releases debuting from McLaren, Porsche, and Ferrari and earning the “Holy Trinity” nickname. Though fiercely individual, each of the trio claimed a hybrid power-train layout.

Of the three, only the Ferrari LaFerrari boasted a V-12 engine— and a raucous, naturally aspirated one, at that. The LaFerrari also happened to be the most powerful (and, unofficially at least) the most charismatic of the wild bunch. Eponymously named to suggest it was the quintessence of the Ferrari nameplate, the 950 hp hypercar may go down in history not only as the pinnacle of its era, but also as one of the greatest prancing horses of all time.

McLaren P1

Of the three renowned hybrid hypercars that debuted in 2013, two (the Ferrari LaFerrari and Porsche 918 Spyder) hailed from long-established carmakers, while the other—the McLaren P1—was a relative newbie on the scene. Not that the British manufacturer hadn’t earned itself a spot in the hypercar pantheon with the 1990s-era legendary F1, but the lengthy absence made building this flagship like starting from scratch.

McLaren used advanced carbon-fiber construction based on its lesser, more approachable (relatively) offerings, but the top dog P1 claimed a screaming 903 hp and a remarkably lightweight chassis, which made it a more than worthy contender against the supercar establishment of the time. B.W.

Porsche 918 Spyder

The 918 Spyder was a true game changer, demonstrating the potential of plug-in hybrid technology in the supercar stratosphere. A naturally aspirated, 4.6-litre V-8 with 599 hp got added power from two electric motors, for a total output of 877 hp and 944 ft lbs of near instant-on torque.

Penned by Porsche’s chief designer, Michael Mauer, the 918 was first shown at the Geneva Motor Show in 2010 as a concept to gauge market interest, going into production in late 2013 with a base MSRP of $845,000. The entire allocation of—surprise—918 units, sold out by the end of 2014, so eager were VIP Porschephiles to acquire the most powerful street-going Porsche ever made. Production ended by mid-2015, and the 918 remains a highly desirable collector car today. Robert Ross

Koenigsegg Regera

Sweden may be known largely as the home of proletarian transportation king Volvo, but sports car enthusiasts also know it as the land of Koenigsegg. And one of the mightiest models to leave that factory is the Regera, brainchild of company founder Christian von Koenigsegg who was, reportedly, inspired after a few sprints in a Tesla Model S P95.

The Regera, however, runs on hybrid power combining three electric motors with a 5-litre V-8. The power-train configuration, in total, produces a staggering 1,700 hp—all of which completely and wonderfully upends the image of Swedes being models of self-restraint. M.C.

Lamborghini Huracán Performante

Lamborghini’s Huracán was no slouch, a flying wedge of a car powered by a 10-cylinder engine producing a touch over 600 hp. But four years after the model’s debut in 2014, it was decided that this Italian raging bull needed a track-focused makeover. Carbon-fibre bumpers, skirts and an adjustable wing removed weight and added downforce, while an engine massage bumped horsepower up 5 percent and took the coupe’s zero-to-100 km/h time down to just less than 3 seconds.

The interior was just as race oriented, with sports seats and digital speedometer off the Aventador. All that added up to a brief but celebrated 2016 track record at Germany’s haloed Nürburgring, not bad at all for a company whose roots were in tractors. M.C.

Pagani Huayra Roadster

Follow-ups to massive debuts are tough nuts to crack. But Argentine engineer Horatio Pagani did just that with the Huayra, the successor to his stop-the-presses Zonda. Back in the engine bay is a monstrous AMG-tuned power plant, this time a six-litre twin-turbo V-12 producing 738 hp.

Wrapped around the driver and passenger of this roofless wonder is a tub made from a combination of carbon fibre and titanium for greater stiffness and lighter weight. But those are just the raw specs for a vehicle perhaps best known for being as meticulously refined as a Swiss watch, a true tastemaker’s triumph. M.C.

Ruf CTR 30th Anniversary Edition

Ruf’s 340 km/h Yellowbird may have looked like a slightly tweaked Porsche 911, but the heavily modified creation was nothing short of groundbreaking, vanquishing titans like the Ferrari F40 and Lamborghini Countach in a 1987 Road & Track magazine cover story. Its legend became cemented with a Nürburgring-shredding session in the “Faszination” video.

The latest CTR, marking its 30th anniversary, once again appears approachable at first glance, but this time around it boasts an entirely bespoke carbon-fiber chassis hiding a cornucopia of exotic hardware, from inboard suspension to a quick-revving 700 hp power plant. At once classic and futuristic, the CTR marks a momentous milestone against the original Yellowbird, offering a wildly capable supercar that hides in a discreetly familiar body. B.W.

McLaren Senna

Being named after the legendary Formula 1 world champion Ayrton Senna guarantees the fearsome McLaren Senna rarified status. But it’s the car’s savage, rock-out-of-a-catapult performance and breathtaking capability, both on and off the racetrack, that heighten its near-mythical appeal.

Unveiled in 2017 with production set at 500 examples, the $960,000 Senna is a road-legal, super-lightweight track missile powered by a 789 hp, mid-mounted four-litre twin-turbo V-8. It can run zero-to-100 km/h in just 2.8 seconds and hit a top speed of 340 km/h. While we think the F1 still ranks as the ultimate McLaren, the Senna is certainly right behind it. H.W.

Ferrari SF90 Stradale

While the days of Maranello’s 12-cylinder halo rockets may be fading in today’s eco-climate, the eight-cylinder SF90 Stradale more than delivers. Billed as a street car tribute to Ferrari’s SF90 Formula 1 machine, the SF90 Stradale is an unabashed hypercar boasting 1,000 hp from three electric motors and a twin-turbo V-8.

Its combination of exceptional hybrid power-train performance and dramatic looks pull from the best of existing aft-engined models. Note the nod to the 488’s flank scoops as well as to the marque’s racing pedigree—the nose simply screams motorsport, which this car salutes by name: Scuderia Ferrari, 90 years. M.C.

Bugatti Chiron Super Sport 300+

On August 2, 2019, Bugatti’s Chiron Super Sport became the first series-production automobile to break the 482 km/h mark on a German test track with official Bugatti test driver and Le Mans–winner Andy Wallace behind the wheel. Inspired by that achievement, the manufacturer created the eponymously named Chiron Super Sport 300+.

Limited to 30 examples worldwide, it’s distinguished by carbon bodywork that extends the longtail by 9.8 inches, along with aero enhancements that improve high-speed performance by further lowering drag and increasing downforce. It’s about power too, where the 8.0-litre, W-16 quad-turbocharged engine produces 1,600 hp, 100 hp more than a “garden-variety” Chiron. As regards fuel consumption, depending on how fast you drive, your mileage may vary. R.R.

SSC Tuatara

To reach 482 km/h . That’s the target that Washington State–based SSC North America has for its new SSC Tuatara hypercar. To hit that mark, the carbon-fiber–bodied Tuatara—named after a spiny lizard found in New Zealand—carries a 5.9-litre twin-turbo V-8 packing a massive 1,726 hp.

Production has already kicked off with the goal to build 100 examples, each priced at $1.6 million. SSC isn’t new to the high-speed business. In 2007, its 1,287 hp Ultimate Aero clocked 412 km/h . The record stood for three years before Bugatti’s Veyron Super Sports came along. But on January 17, 2021, the SSC Tuatara took the record back with two runs that averaged 455 km/h , and the results were verified by Racelogic. More recently still, it officially clocked 474 km/h. H.W.

Lamborghini Essenza SCV12

While Lamborghini’s lineup of 21st century road cars is more outlandish than ever, nothing earns street cred more than how track-worthy a model is. Enter the Essenza SCV12, Lambo’s postmodern hat tip to track specials of yore like the Diablo GTR and Miura Jota.

Freed from the constraints of road legality, the Essenza uncorks Lamborghini’s naughtiest impulses from bow to stern. Extreme bodywork yields over 2,600 pounds of downforce, more than a GT3 race car and, liberated from emissions equipment, the hulking 6.5-litre, 819 hp engine is Lambo’s most powerful V-12 yet. Then there’s the futurist cockpit, which features a button-and-dial-clad steering yoke that wouldn’t be out of place in a Formula 1 car. And although the 40 buyers of the $2.6 million Essenza won’t have their own competition series, Lamborghini promises Essenza-only track days that should satisfy the owners’ race cravings. B.W.

Aston Martin Valkyrie

Supercar greatness in the form of Aston Martin’s Valkyrie is now in production. The model is a new benchmark for the automaker when it comes to street-legal, production-car performance. It’s what happens when you bolt a 1,000 hp, 6.5-litre V-12, along with a 160 hp Rimac-developed hybrid-electric system, into a lightweight, super-strong carbon monocoque.

And if that wasn’t impressive enough, remember the car has been designed by Adrian Newey, a rock star in Formula 1 design and the current chief technical officer for Red Bull Racing. Production will be limited to 150 examples, each costing $3.2 million. H.W.

Lamborghini Countach LPI 800-4

It’s been a half century since Lamborghini gobsmacked the supercar world with the Countach and its wedge-shaped silhouette. Now, more than 50 years later, the Countach LPI 800-4 revives the iconic nameplate with a similar-but-not-the-same take on the model’s age-old formula.

Some haters have dismissed the new Countach as a needless nod to the past; not only is the name dear to enthusiasts’ hearts, but so are signature design cues like the massive side-mounted ducts and air inlets at the haunches. However, the heart of the LPI 800-4 speaks more to Lamborghini’s hereafter than any sheetmetal could, namely an 802 hp, hybrid power train that seals the deal on the future relevance of the Raging Bull marque. B.W.

Rimac Nevera

Landmark cars often hail from unexpected places, but the Rimac Nevera has dealt earth-shattering blows to the supercar microcosm. For starters, the battery-powered Nevera obliterated internal combustion records by routing 1,914 hp to all four wheels, eclipsing zero-to-100 km/h times of everything from McLarens to Koenigseggs. More shockingly, the EV hypercar is the brainchild of 33-year old Croatian wunderkind Mate Rimac, who founded the firm in 2011.

The Rimac Nevera’s early impact arose from its sensational performance stats, but the legacy of this hypercar will transcend a mere model. In summer 2021, the Croatian startup purchased a majority stake in Bugatti, marking the first (and likely not the last) time a legacy supercar brand falls under the control of an EV upstart. B.W.

Mercedes-AMG One

How can a car that just entered production rank as one of the supercar “greats” of the 21st century? Because we’re oh-so-confident that the 1,000 hp Mercedes-AMG Formula 1 racer for the street appears next summer, it continue to be mind-blowing for years to come.

Unveiled back in 2017 as the Project One concept, this road-going monster was plagued by technical challenges, but then there’s a lot going on when you basically build a Formula 1 car you can take on the freeway.

Powered by a hybrid-boosted, 1.6-litre turbo V-6 and a trio of electric motors, it’s expected to cover zero to 200 km/h in less than 6 seconds and top out at 350 km/h. Not surprisingly, all 275 examples of these $2.6 million tour de forces are taken. H.W.

Koenigsegg Jesko

Back in 2017, Sweden’s Christian von Koenigsegg saw his Agera RS become the world’s fastest production car with a two-way top speed of 447 km/h. The Agera’s successor, the mega-winged, 1,660 hp Jesko—named after Christian’s father—may have what it takes to top the Bugatti Chiron Super Sport’s 490 km/h mark.

The $3 million Jesko’s go-fast technology includes a screaming, 5.0-litre twin-turbo V-8, which features the world’s lightest V-8 crankshaft, weighing a mere 28 pounds. It’s no wonder that all 125 examples of the model scheduled for production have been presold. H.W.

Pininfarina Battista

Automotive nameplates don’t come more legendary than Pininfarina. The Italian studio’s 62-year association with Ferrari, for example, created such icons as the 275 GTB, 365 GTB/4 Daytona and that Tom Selleck Magnum P.I. classic, the 308 GTS. The Cadillac Atlante? Not so much.

With a little help from India’s Mahindra Group, who rescued Pininfarina in late 2015, and the Croatian EV electric geniuses at Rimac, comes the sensational Pininfarina Battista hypercar. Packing 1,900 hp and 2,300 Nm of torque from its 120 kwh lithium-ion battery pack and quad motors, this truly-gorgeous electric two-seat coupe can slingshot from zero to 100 km/h in 1.8 seconds, and run zero to 300 km/h in 12 seconds. Flat out, it’ll hit 350 km/h before the electronic nannies kick in.

The first of the 150 cars being built—priced starting at $2.2 million each—has already been delivered. Want something really special? There’s a lavishly equipped Anniversario edition, of which only five will be produced. They’re priced closer to $2.9 million but, alas, all have been sold. H.W.

Lotus Evija

It’s simply the most powerful series-production road car ever built. It packs an astonishing 2,011 hp and 141 Nm of torque. That’s enough to catapult this hip-high projectile from zero to 100 km/h in less than three seconds and whisk it from zero to 300 km/h in just 9.1.

This is the all-electric Lotus Evija from the fabled British sports-car maker founded by the visionary Colin Chapman back in 1952. The new Evija—it supposedly means “the living one”—is all carbon-fiber monocoque, Le Mans–inspired aerodynamics and a state-of-the-art electric power train developed by the technical wizards at Williams Advanced Engineering.

And what a power train. With prodigious electric motors at each wheel, and a mid-mounted battery pack echoing Lotus’ tradition of mid-engine positioning, pure electric driving range is around 250 miles. Hook it up to an 800 kw charger and the whole pack will replenish in just nine minutes.

Only 130 examples of the Evija will be built, with first deliveries in early 2023. As for the price, expect to pay around $2.3 million. H.W.

Pagani Utopia

Utopia is defined as “an imagined place where everything is perfect,” an ideal Horacio Pagani has been chasing since he became a boutique carmaker some 30 years ago. His latest stab at perfection replaces the Huayra, and edges toward that goal by combining his familiar AMG-sourced twin-turbo 852 hp V-12 with the choice of an automated single clutch, or a fully traditional three-pedal manual gearbox. The former is a staple for the power-addled set; the latter, catnip to enthusiasts addicted to driving with all four limbs.

Pagani’s (predominantly) analog Utopia makes a case for blending old and new in familiar-yet-fresh packaging, while innovating with a chassis that leverages the best of both carbon fibre and titanium. Horacio’s new hypercar breaks new ground while resisting the urge to add a hybrid or electric drivetrain, making a power play for both modernity and nostalgia available to only 99 customers. B.W.

Ferrari Daytona SP3

The Icona series of limited-production models tips a hat to the past by wrapping modern underpinnings with retro-futuristic skins. The third Icona to hail from Modena is the Daytona SP3, which recalls the Ferrari 330 P4s which finished first, second, and third at the 24 Hours of Daytona in 1967.

Though its air intakes and aerodynamics are functional, the spirit of the SP3 is strictly nostalgic—specifically its naturally aspirated V-12 that revs to 9,500 rpm and produces 829 horsepower. From its swollen fenders to its dramatically straked rear end, the $2.2 million Daytona SP3 will serve as kinetic art when its 599 owners take delivery of their special steeds. B.W.

McLaren Solus GT

McLaren threw out the rulebook when imagining the Solus GT. Rather than sticking to hypercar conventions, the Woking-based brand went for broke with a single-seater, track-only special that will only see 25 examples built. Gamers might spot the resemblance to McLaren’s Vision GT, the fictional racer seen in the video game Gran Turismo Sport.

This time around, the physical car departs from McLaren’s V-8 tradition by packing a 5.2-litre V-10 capable of spinning at 10,000 rpm and launching to 100 km/h in less than 2.5 seconds. If the nearly 830 horsepower power plant isn’t compelling enough, the Solus GT’s featherweight 1 tonne mass and 1,200 kgs of downforce should make this ultra-rare model super collectible down the line. B.W.

Hennessey Venom F5 Roadster

We loved the outrageous 1,817 hp Venom F5 Coupe from maverick Texas supercar builder John Hennessey and his team at Hennessey Special Vehicles. When it debuted back in 2021, the Venom F5 was fast, furious and designed to shatter the elusive 482 km/h barrier. While it has yet to hit that particular bullseye, a recorded max of 437 km/h certainly shows its potential.

Now it’s the turn of the new, Venom F5 Roadster to go for 482 km/h. Being powered by the same 1,817 hp, 6.6-litre twin-turbo “Fury” V-8 as the coupe, and weighing only 45 pounds more, the open-top torpedo could have that speed benchmark clearly in the crosshairs. Just know that the lift-out, featherweight carbon-fiber roof panel—it weighs just 8 kgs—will have to stay in place for the Roadster to get anywhere close to the 300 club.

Yet, to us, the beauty of this Venom F5 Roadster will be taking off the top and hearing the full thunder of those eight cylinders as it roars to its 8,500 rpm red line. Hennessey plans to build 30 examples of the Roadster, each priced at a cool $3 million. H.W.

Subscribe to the Newsletter

Recommended for you

First Drive: The Lotus Emeya Targets Porsche, Mercedes, and Lucid With Its 70 kw Performance

What the all-electric sedan lacks in cohesive styling is more than made up for in muscular athleticism.

By Tim Pitt

July 22, 2024

Why BMW’s First Electric Cars Are Future Classics

Many things still feel contemporary about the BMW i3 and i8.

July 11, 2024

You may also like.

By Josh Bozin

24/07/2024

You may also like.

5 Lounge Chairs That Add Chic Seating to Your Space

Daybeds, the most relaxed of seating solutions, offer a surprising amount of utility.

Chaise longue, daybed, recamier, duchesse brisée—elongated furniture designed for relaxing has a roster of fancy names. While the French royal court of Louis XIV brought such pieces to prominence in fashionable European homes, the general idea has been around far longer: The Egyptian pharaohs were big fans, while daybeds from China’s Ming dynasty spurred all those Hollywood Regency fretwork pieces that still populate Palm Beach living rooms. Even Mies van der Rohe, one of design’s modernist icons, got into the lounge game with his Barcelona couch, a study of line and form that holds up today.

But don’t get caught up in who invented them, or what to call them. Instead, consider their versatility: Backless models are ideal in front of large expanses of glass (imagine lazing on one with an ocean view) or at the foot of a bed, while more structured pieces can transform any corner into a cozy reading nook. Daybeds may be inextricably linked to relaxation, but from a design perspective, they put in serious work.

Emmy, Egg Collective

In designing the Emmy chaise, the Egg Collective trio of Stephanie Beamer, Crystal Ellis and Hillary Petrie, who met as students at Washington University in St. Louis, aimed for versatility. Indeed, the tailored chaise looks equally at home in a glass skyscraper as it does in a turn-of-the-century town house. Combining the elegance of a smooth, solid oak or walnut frame with the comfort of bolsters and cushioned upholstery or leather, it works just as well against a wall or at the heart of a room. From around $7,015; Eggcollective.com

Plum, Michael Robbins

Plum, Michael Robbins

Woodworker Michael Robbins is the quintessential artisan from New York State’s Hudson Valley in that both his materials and methods pay homage to the area. In fact, he describes his style as “honest, playful, elegant and reflective of the aesthetic of the Hudson Valley surroundings”. Robbins crafts his furniture by hand but allows the wood he uses to help guide the look of a piece. (The studio offers eight standard finishes.) The Plum daybed, brought to life at Robbins’s workshop, exhibits his signature modern rusticity injected with a hint of whimsy thanks to the simplicity of its geometric forms. Around $4,275; MichaelRobbins.com

Kimani, Reda Amalou Design

French architect and designer Reda Amalou acknowledges the challenge of creating standout seating given the number of iconic 20th-century examples already in existence. Still, he persists—and prevails. The Kimani, a bent slash of a daybed in a limited edition of eight pieces, makes a forceful statement. Its leather cushion features a rolled headrest and rhythmic channel stitching reminiscent of that found on the seats of ’70s cars; visually, these elements anchor the slender silhouette atop a patinated bronze base with a sure-handed single line. The result: a seamless contour for the body. Around $33,530; RedaAmalou

Dune, Workshop/APD

From a firm known for crafting subtle but luxurious architecture and interiors, Workshop/APD’s debut furniture collection is on point. Among its offerings is the leather-wrapped Dune daybed. With classical and Art Deco influences, its cylindrical bolsters are a tactile celebration, and the peek of the curved satin-brass base makes for a sensual surprise. Associate principal Andrew Kline notes that the daybed adeptly bridges two seating areas in a roomy living space or can sit, bench-style, at the foot of a bed. From $13,040; Workshop/ APD

Sherazade, Edra

Designed by Francesco Binfaré, this sculptural, minimalist daybed—inspired by the rugs used by Eastern civilizations—allows for complete relaxation. Strength combined with comfort is the name of the game here. The Sherazade’s structure is made from light but sturdy honeycomb wood, while next-gen Gellyfoam and synthetic wadding aid repose. True to Edra’s amorphous design codes, it can switch configurations depending on the user’s mood or needs; for example, the accompanying extra pillows—one rectangular and one cylinder shaped— interchange to become armrests or backrests. From $32,900; Edra

You may also like.

By Josh Bozin

24/07/2024

22/07/2024

Watches & Wonders 2024 Showcase: Hermès

We head to Geneva for the Watches & Wonders exhibition; a week-long horological blockbuster featuring the hottest new drops, and no shortage of hype.

With Watches & Wonders 2024 well and truly behind us, we review some of the novelties Hermès presented at this year’s event.

—

HERMÈS

Moving away from the block colours and sporty aesthetic that has defined Hermès watches in recent years, the biggest news from the French luxury goods company at Watches & Wonders came with the unveiling of its newest collection, the Hermès Cut.

It flaunts a round bezel, but the case middle is nearer to a tonneau shape—a relatively simple design that, despite attracting flak from some watch aficionados, works. While marketed as a “women’s watch”, the Cut has universal appeal thanks to its elegant package and proportions. It moves away from the Maison’s penchant for a style-first product; it’s a watch that tells the time, not a fashion accessory with the ability to tell the time.

Hermès gets the proportions just right thanks to a satin-brushed and polished 36 mm case, PVD-treated Arabic numerals, and clean-cut edges that further accentuate its character. One of the key design elements is the positioning of the crown, boldly sitting at half-past one and embellished with a lacquered or engraved “H”, clearly stamping its originality. The watch is powered by a Hermès Manufacture movement H1912, revealed through its sapphire crystal caseback. In addition to its seamlessly integrated and easy-wearing metal bracelet, the Cut also comes with the option for a range of coloured rubber straps. Together with its clever interchangeable system, it’s a cinch to swap out its look.

It will be interesting to see how the Hermès Cut fares in coming months, particularly as it tries to establish its own identity separate from the more aggressive, but widely popular, Ho8 collection. Either way, the company is now a serious part of the dialogue around the concept of time.

—

Read more about this year’s Watches & Wonders exhibition at robbreport.com.au

You may also like.

22/07/2024

Living La Vida Lagerfeld

The world remembers him for fashion. But as a new tome reveals, the iconoclastic designer is defined as much by extravagant, often fantastical, homes as he is clothes.

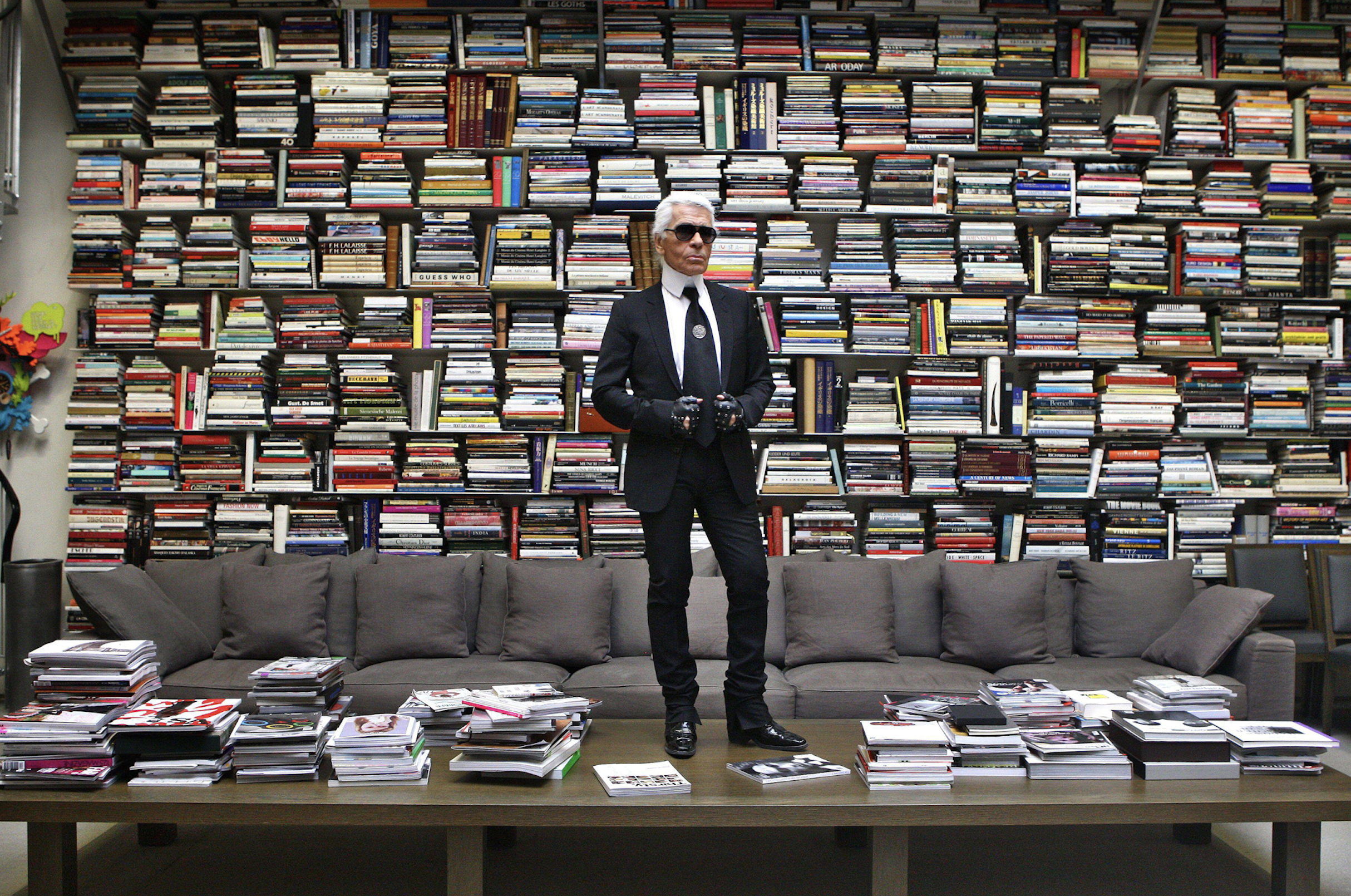

“Lives, like novels, are made up of chapters”, the world-renowned bibliophile, Karl Lagerfeld, once observed.

Were a psychological-style novel ever to be written about Karl Lagerfeld’s life, it would no doubt give less narrative weight to the story of his reinvigoration of staid fashion houses like Chloe, Fendi and Chanel than to the underpinning leitmotif of the designer’s constant reinvention of himself.

In a lifetime spanning two centuries, Lagerfeld made and dropped an ever-changing parade of close friends, muses, collaborators and ambiguous lovers, as easily as he changed his clothes, his furniture… even his body. Each chapter of this book would be set against the backdrop of one of his series of apartments, houses and villas, whose often wildly divergent but always ultra-luxurious décor reflected the ever-evolving personas of this compulsively public but ultimately enigmatic man.

With the publication of Karl Lagerfeld: A Life in Houses these wildly disparate but always exquisite interiors are presented for the first time together as a chronological body of work. The book indeed serves as a kind of visual novel, documenting the domestic dreamscapes in which the iconic designer played out his many lives, while also making a strong case that Lagerfeld’s impact on contemporary interior design is just as important, if not more so, than his influence on fashion.

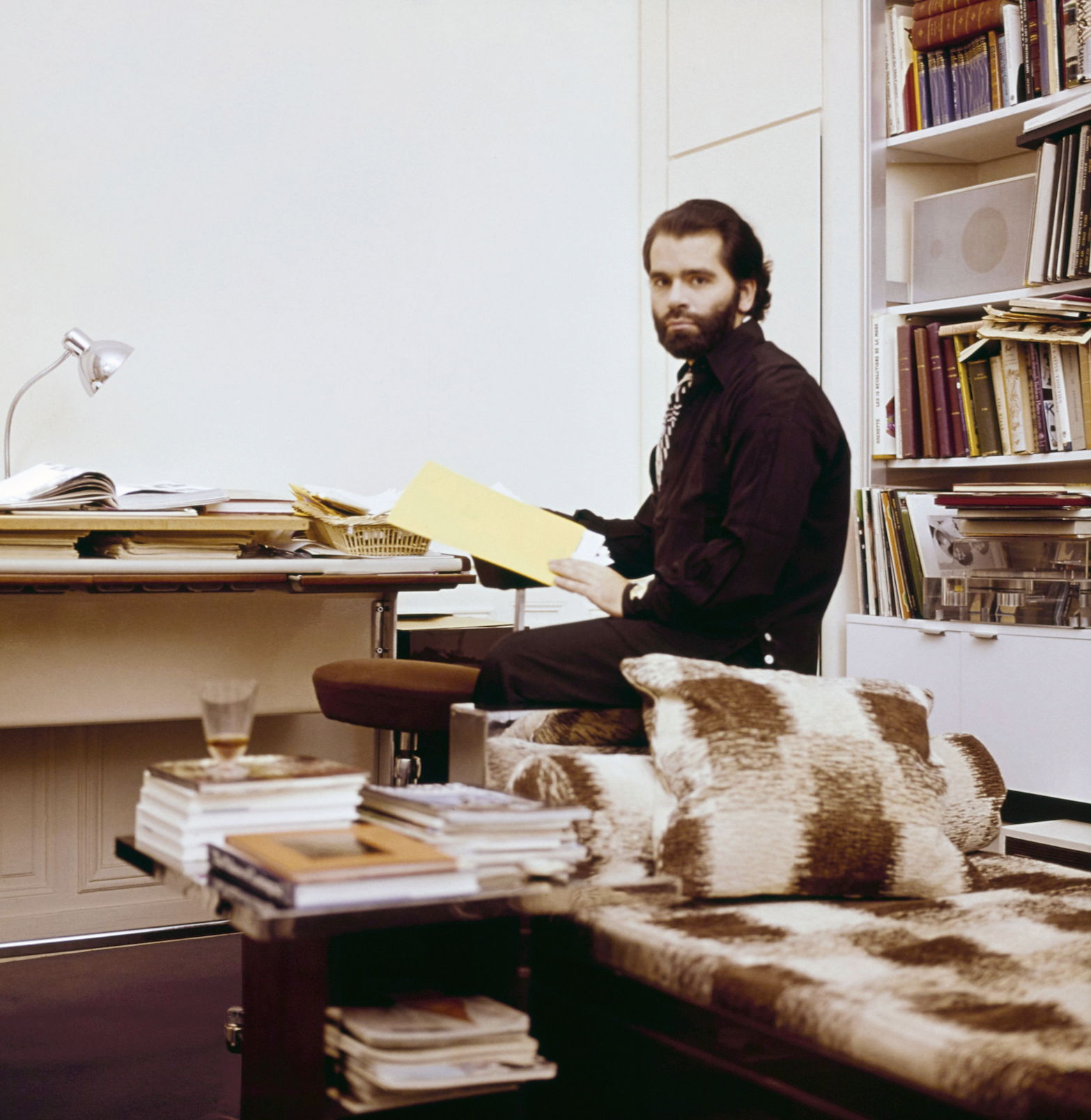

In fact, when the first Lagerfeld interior was featured in a 1968 spread for L’OEil magazine, the editorial describes him merely as a “stylist”. The photographs of the apartment in an 18th-century mansion on rue de Université, show walls lined with plum-coloured rice paper, or lacquered deepest chocolate brown in sharp contrast to crisp, white low ceilings that accentuated the horizontality that was fashionable among the extremely fashionable at the time. Yet amid this setting of aggressively au courant modernism, the anachronistic pops of Art Nouveau and Art Deco objects foreshadow the young Karl’s innate gift for creating strikingly original environments whose harmony is achieved through the deft interplay of contrasting styles and contexts.

Lagerfeld learned early on that presenting himself in a succession of gem-like domestic settings was good for crafting his image. But Lagerfeld’s houses not only provided him with publicity, they also gave him an excuse to indulge in his greatest passion. Shopping!

By 1973, Lagerfeld was living in a new apartment at Place Saint–Sulpice where his acquisition of important Art Deco treasures continued unabated. Now a bearded and muscular disco dandy, he could most often be found in the louche company of the models, starlets and assorted hedonistic beauties that gathered around the flamboyant fashion illustrator Antonio Lopez. Lagerfeld was also in the throes of a hopeless love affair with Jacques de Bascher whose favours he reluctantly shared with his nemesis Yves Saint Laurent.

He painted the rooms milky white and lined them with specially commissioned carpets—the tawny patterned striations of which invoked musky wild animal pelts. These lent a stark relief to the sleek, machine-age chrome lines of his Deco furnishings. To contemporary eyes it remains a strikingly original arrangement that subtly conveys the tensions at play in Lagerfeld’s own life: the cocaine fuelled orgies of his lover and friends, hosted in the pristine home of a man who claimed that “a bed is for one person”.

In 1975, a painful falling out with his beloved Jacques, who was descending into the abyss of addiction, saw almost his entire collection of peerless Art Deco furniture, paintings and objects put under the auctioneer’s hammer. This was the first of many auction sales, as he habitually shed the contents of his houses along with whatever incarnation of himself had lived there. Lagerfeld was dispassionate about parting with these precious goods. “It’s collecting that’s fun, not owning,” he said. And the reality for a collector on such a Renaissance scale, is that to continue buying, Lagerfeld had to sell.

Of all his residences, it was the 1977 purchase of Hôtel Pozzo di Borgo, a grand and beautifully preserved 18th-century house, that would finally allow him to fulfill his childhood fantasies of life in the court of Madame de Pompadour. And it was in this aura of Rococó splendour that the fashion designer began to affect, along with his tailored three-piece suits, a courtier’s ponytailed and powdered coif and a coquettish antique fan: marking the beginning of his transformation into a living, breathing global brand that even those with little interest in fashion would immediately recognise.

Lagerfeld’s increasing fame and financial success allowed him to indulge in an unprecedented spending frenzy, competing with deep-pocketed institutions like the Louvre to acquire the finest, most pedigreed pearls of the era—voluptuously carved and gilded bergères; ormolu chests; and fleshy, pastel-tinged Fragonard idylls—to adorn his urban palace. His one-time friend André Leon Talley described him in a contemporary article as suffering from “Versailles complex”.

However, in mid-1981, and in response to the election of left-wing president, François Mitterrand, Lagerfeld, with the assistance of his close friend Princess Caroline, became a resident of the tax haven of Monaco. He purchased two apartments on the 21st floor of Le Roccabella, a luxury residential block designed by Gio Ponti. One, in which he kept Jacques de Bascher, with whom he was now reconciled, was decorated in the strict, monochromatic Viennese Secessionist style that had long underpinned his aesthetic vocabulary; the other space, though, was something else entirely, cementing his notoriety as an iconoclastic tastemaker.

Lagerfeld had recently discovered the radically quirky designs of the Memphis Group led by Ettore Sottsass, and bought the collective’s entire first collection and had it shipped to Monaco. In a space with no right angles, these chaotically colourful, geometrically askew pieces—centred on Masanori Umeda’s famous boxing ring—gave visitors the disorientating sensation of having entered a corporeal comic strip. By 1991, the novelty of this jarring postmodern playhouse had inevitably worn thin and once again he sent it all to auction, later telling a journalist that “after a few years it was like living in an old Courrèges. Ha!”

In 1989, de Bascher died of an AIDS-related illness, and while Lagerfeld’s career continued to flourish, emotionally the famously stoic designer was struggling. In 2000, a somewhat corpulent Lagerfeld officially ended his “let them eat cake” years at the Hôtel Pozzo di Borgo, selling its sumptuous antique fittings in a massive headline auction that stretched over three days. As always there were other houses, but now with his longtime companion dead, and his celebrity metastasising making him a target for the paparazzi, he began to look less for exhibition spaces and more for private sanctuaries where he could pursue his endless, often lonely, work.

His next significant house was Villa Jako, named for his lost companion and built in the 1920s in a nouveau riche area of Hamburg close to where he grew up. Lagerfeld shot the advertising campaign for Lagerfeld Jako there—a fragrance created in memorial to de Bascher. The house featured a collection of mainly Scandinavian antiques, marking the aesthetic cusp between Art Nouveau and Art Deco. One of its rooms Lagerfeld decorated based on his remembrances of his childhood nursery. Here, he locked himself away to work—tellingly—on a series of illustrations for the fairy tale, The Emperor’s New Clothes. Villa Jako was a house of deep nostalgia and mourning.

But there were more acts—and more houses—to come in Lagerfeld’s life yet. In November 2000, upon seeing the attenuated tailoring of Hedi Slimane, then head of menswear at Christian Dior, the 135 kg Lagerfeld embarked on a strict dietary regime. Over the next 13 months, he melted into a shadow of his former self. It is this incarnation of Lagerfeld—high white starched collars; Slimane’s skintight suits, and fingerless leather gloves revealing hands bedecked with heavy silver rings—that is immediately recognisable some five years after his death.

The 200-year-old apartment in Quái Voltaire, Paris, was purchased in 2006, and after years of slumber Lagerfeld—a newly awakened Hip Van Winkle—was ready to remake it into his last modernist masterpiece. He designed a unique daylight simulation system that meant the monochromatic space was completely without shadows—and without memory. The walls were frosted and smoked glass, the floors concrete and silicone; and any hint of texture was banned with only shiny, sleek pieces by Marc Newson, Martin Szekely and the Bouroullec Brothers permitted. Few guests were allowed into this monastic environment where Lagerfeld worked, drank endless cans of Diet Coke and communed with Choupette, his beloved Birman cat, and parts of his collection of 300,000 books—one of the largest private collections in the world.

Lagerfeld died in 2019, and the process of dispersing his worldly goods is still ongoing. The Quái Voltaire apartment was sold this year for US$10.8 million (around $16.3 million). Now only the rue de Saint-Peres property remains within the Lagerfeld trust. Purchased after Quái Voltaire to further accommodate more of his books—35,000 were displayed in his studio alone, always stacked horizontally so he could read the titles without straining his neck—and as a place for food preparation as he loathed his primary living space having any trace of cooking smells. Today, the rue de Saint-Peres residence is open to the public as an arts performance space and most fittingly, a library.

You may also like.

By Josh Bozin

24/07/2024

Watch This Space: Mike Nouveau

Meet the game-changing horological influencers blazing a trail across social media—and doing things their own way.

In the thriving world of luxury watches, few people own a space that offers unfiltered digital amplification. And that’s precisely what makes the likes of Brynn Wallner, Teddy Baldassarre, Mike Nouveau and Justin Hast so compelling.

These thought-provoking digital crusaders are now paving the way for the story of watches to be told, and shown, in a new light. Speaking to thousands of followers on the daily—mainly via TikTok, Instagram and YouTube—these progressive commentators represent the new guard of watch pundits. And they’re swaying the opinions, and dollars, of the up-and-coming generations who now represent the target consumer of this booming sector.

—

MIKE NOUVEAU

Can we please see what’s on the wrist? That’s the question that catapulted Mike Nouveau into watch stardom, thanks to his penchant for highlighting incredibly rare timepieces across his TikTok account of more than 400,000 followers. When viewing Nouveau’s attention-grabbing video clips—usually shot in a New York City neighbourhood—it’s not uncommon to find him wrist-rolling some of the world’s rarest timepieces, like the million-dollar Cartier Cheich (a clip he posted in May).

But how did someone without any previous watch experience come to amass such a cult following, and in the process gain access to some of the world’s most coveted timepieces? Nouveau admits had been a collector for many years, but moved didn’t move into horology full-time until 2020, when he swapped his DJing career for one as a vintage watch specialist.

“I probably researched for a year before I even bought my first watch,” says Nouveau, alluding to his Rolex GMT Master “Pepsi” ref. 1675 from 1967, a lionised timepiece in the vintage cosmos. “I would see deals arise that I knew were very good, but they weren’t necessarily watches that I wanted to buy myself. I eventually started buying and selling, flipping just for fun because I knew how to spot a good deal.”

Nouveau claims that before launching his TikTok account in the wake of Covid-19, no one in the watch community knew he existed. “There really wasn’t much watch content, if any, on TikTok before I started posting, especially talking about vintage watches. There’s still not that many voices for vintage watches, period,” says Nouveau. “It just so happens that my audience probably skews younger, and I’d say there are just as many young people interested in vintage watches as there are in modern watches.”

View this post on Instagram

Nouveau recently posted a video to his TikTok account revealing that the average price of a watch purchased by Gen Z is now almost US$11,000 (around $16,500), with 41 percent of them coming into possession of a luxury watch in the past 12 months.

“Do as much independent research as you can [when buying],” he advises. “The more you do, the more informed you are and the less likely you are to make a mistake. And don’t bring modern watch expectations to the vintage world because it’s very different. People say, ‘buy the dealer’, but I don’t do that. I trust myself and myself only.”

—

Read more about the influencers shaking up horology here with Justin Hast, Brynn Wallner and Teddy Baldassare.

You may also like.

By Josh Bozin

24/07/2024

This Pristine 1960 Ferrari 250 Spider Could Fetch $24 Million at Auction

The car wears the same colours and has the same engine it left the factory with.

Some Ferraris are just a little bit more important than others.

Take, for example, the 1960 250 GT SWB California that RM Sotheby’s is auctioning off during this year’s Monterey Car Week. Any example of the open-top beauty would attract interest, but this one just so happens to be the first one that was built.

The 250 is one of the most legendary series of cars in Ferrari history. Between 1952 and 1964, the company released 21 different 250 models—seven for racetracks, 14 for public roads—of which the “Cali Spider” might be the most well regarded, thanks to its potent V-12 and a Pininfarina-penned design that is one of the most beautiful bodies to grace an automobile. The roadster, which was specifically built for the U.S., made its debut in 1957 as a long-wheel-base model (LWB), but it wasn’t until the SWB model debut in 1960 that it became clear how special it was. This example isn’t just the first to roll off the line. It’s the actual car that was used to introduce the world to the model at the 1960 Geneva Motor Show.

Just 56 examples of the 250 GT SWB California Spider would be built by Scaglietti during the three years it was in production. The first of those, chassis 1795 GT, is finished in a glossy coat of Grigio. The two-door had a red leather interior at Geneva but was returned to the factory and re-outfitted with black leather upholstery before being delivered to its original owner, British race car driver John Gordon Bennet. Six-and-a-half decades later the car looks identical to how it did when it left the factory the second time.

In addition to its original bodywork, the chassis 1795 GT features its original engine, gearbox, and rear axle. That mill is the competition-spec Tipo 168, a 3.0-litre V-12 that makes 196.1 kW. That may not sound like much by today’s standards, but, when you consider that the 250 GT SWB California Spider tips the scales around 952 kilograms, it’s more than enough.

The first 250 GT SWB California Spider is scheduled to go up for bid during RM Sotheby’s annual Monterey Car Week auction, which runs from Thursday, August 15, to Saturday, August 17. Unsurprisingly, the house has quite high hopes for the car. The car carries an estimate of between $24 million and $26 million, which could make it one of the most expensive cars ever sold at auction.

You may also like.

By Josh Bozin

24/07/2024