Robb Read: Seiko’s Grand Plan

Seiko once nearly destroyed the luxury watch industry. Now its extraordinary dials and mechanical innovation are earning it cult status.

Related articles

In many ways, Japan does things differently. In place of the mere four seasons that make up a year in much of the world, Japan has measured the passage of time since the sixth century with 24 annual seasons, which are then subdivided into some 72 micro seasons. They are nuanced and observational: uo kori o izuru, a five-day window when fish emerge from the ice in February, or kawazu hajimete naku, when frogs start singing in the early days of May. Time operates by a different set of rules here. Einstein be damned.

“It’s unique, the feeling of how we perceive time, because we don’t try to control it,” says Shuji Takahashi, Seiko Holdings’ president, COO and CMO. “It’s more that we live together with time. We try to harmonise ourselves to the flow of time that exists.”

The Japanese may be onto something. Seiko Holdings’ Grand Seiko, along with its ultra-high-end sister brand, Credor, is increasingly gaining a worldwide cult status thanks to its dials and movements, many inspired by the island nation’s perennially changing landscape.

It’s certainly not the kind of romanticism you would imagine from two names born under the shadow of Seiko, the company that nearly killed the entire high-end watch industry with its cheap, battery-powered and ultra-precise quartz movements in the 1970s. But these two small-batch brands have been steadily building prestige beyond their borders as the digital age lifted the veil on Seiko’s best-kept secrets. Buoyed by its increasing popularity, Grand Seiko, founded in 1960, began selling outside Japan in 2010 and was spun off from the Seiko brand in 2017. It has since had massive growth and hype on a scale that many Swiss watchmakers, selling in the US for over a century, can only dream of.

Some Grand Seiko collectors own enough models to dangle a watch from every finger. John Chiang, a 40-year-old executive at a California manufacturing company, has acquired nine in the mere two years since some watch-collector friends introduced him to the brand. Chiang started out as an Omega collector before moving into Rolex and Patek Philippe and, most recently, independents such as F. P. Journe. “A lot of my friends in the Patek Philippe crowd said it was a brand I should check out,” says Chiang. “Seiko has been around for a long time—but I had never associated them with high horology. Once I did more research and started to understand their philosophy, I was even more interested.”

Collectors are snatching up new models at retail, where they’re priced from $4,000 for a basic quartz style to $110,000 for a highly decorated platinum version with Spring Drive technology (more on that below), and the newfound fascination with Grand Seiko is resulting in a boom on the secondary market as well, where sales last year included a 2013 steel Grand Seiko limited-edition SBGW047 for US$6,875 (approx. $10,040) at Christie’s and a 2011 limited-edition platinum SBGW039 for CHF 18,750 (approx. $28,780) at Phillips. Both went for more than double their top estimates. The vintage market, though, is a bit murkier to navigate for Grand Seiko than for Swiss timepieces. “They’re still undervalued,” says dealer Eric Wind of Wind Vintage. “But they’re hard to find Stateside, because they’re almost all in Asia. It’s hard to know whether what you are buying is authentic because there is little information on them.”

What is drawing interest in Grand Seiko, both vintage and modern, is a Zen-like balance among aesthetics, technical prowess and a poetic approach to the creation of time, making these watches a covetable alternative to Swiss timepieces. While much of Grand Seiko’s mechanics and design rely on traditional European craftsmanship, it’s the brand’s unorthodox spin on time-tested rules that have propelled the company into the spotlight. Much like Japanese culture, the watches are rooted in a strict ethos of precision combined with an inherent desire to think outside the box.

Case in point: Grand Seiko’s Spring Drive technology is a groundbreaking invention, consisting of a mechanical movement with a hybrid regulating system that uses quartz to achieve extreme accuracy without a battery. Doggedly insistent upon exactness, Grand Seiko prides itself on a standard for timekeeping accuracy that’s more rigorous than the certification rules for the Official Swiss Chronometer Testing Institute (COSC). Mechanical watches undergo more temperature testing (twice each at 8, 23 and 38°C versus once) and are tested in more positions (six versus five) and for more days (17 versus 15) than most watches coming out of the motherland. The company also touts its watches equipped with its Hi-Beat movement. The mechanical Hi-Beat 36000 GMT’s caliber 9S86 delivers an accuracy of +5 to -3 seconds per day with a hefty amount of power reserve (55 hours), beating at a frequency of 36,000 vibrations per hour (10 beats per second). To put into perspective how fast it’s vibrating while still maintaining extraordinary accuracy, a typical mechanical watch operates with 28,800 vph.

Technical statistics like these drive hard-core collectors mad with enthusiasm, yet Grand Seiko was not on most American collectors’ radars until recently. “I didn’t think it was going to sell to our clients, because they want a Swiss brand and aren’t going to buy anything with ‘Seiko’ on it,” says Damon Gross, CEO of Colorado-based retailer Hyde Park Jewelers, an early adopter of Grand Seiko. “But within 18 months it was our number-two watch brand.” Grand Seiko’s first stand-alone store, in Beverly Hills, was even more successful. It reportedly sold out of select limited-edition models such as the original SBGA211 and the new blue SBGA407 within days of opening.

Grand Seiko, however, is not only trying to one-up the Swiss with clever engineering for tech geeks. It’s also embracing its unique heritage, with artful dials and movements designed as tributes to Japan’s landscapes and culture. Designer Shinichiro Kubo conceived the delicately textured, three-dimensional dial and case for the Snowflake watch based on a childhood memory of visiting the Hokuriku region of northern Japan. The Hotokuji temple in Kiryu was the inspiration for the dial of the Grand Seiko Heritage Collection limited-edition SBGH269. The dial borrows its rich ruby hue from the autumn maple leaves reflected on the temple’s polished wood floor, and the gold minute markers and seconds hand mirror the rays of sun that pierce the windows.

Nature’s beauty and its cycles aren’t just weaved in for decor; the mechanics evoke the symmetry of Japan’s countryside. Flip over the Spring Drive 8 Day Power Reserve and you’ll see that its caliber 9R01 movement has a bridge that traces the outline of the famous volcano Mount Fuji. The polished rubies and blued screws that hold the movement together mimic the pattern of the city lights of Suwa, which sit below the company’s Micro Artist Studio.

Located in Shiojiri, in Japan’s Nagano Prefecture, this studio is Japan’s temple of high horology, where watches bearing the Credor name are created. Credor is a separate brand whose artisans and watchmakers occasionally work on some of Grand Seiko’s elite movements. If Grand Seiko watches are the icons of Japanese luxury watchmaking, Credor timepieces are the holy grails. While watches in the Grand Seiko collection are a mix of high-level mechanics with machine-made parts for larger-scale production, much like ready-to-wear clothing, each Credor piece is carefully assembled and finished by hand by a master watchmaker. But unless you’re a bona fide connoisseur, you’ve probably never heard of them. Only the most elite collectors can get their hands on a Credor, including its sonnerie (a watch that signals the time through sound) and minute repeater (a watch that sounds the time on demand by the wearer), not only because the brand is still available exclusively in Japan, but also because only four or five of each are made a year at a price tag of roughly $220,000 for the sonnerie and $490,000 for the minute repeater. A Credor rarely, if ever, shows up at auction.

Inside the studio on a crisp, sunny day, the Japanese artisans are huddled over the same equipment you would find in Switzerland’s main watchmaking hub, Vallée de Joux, assembling movements, painting porcelain dials and polishing microscopic parts by hand. It’s hard to believe the team hasn’t descended from generations of watchmakers who’ve passed down their technical knowledge for centuries, like its competitors 10,000 kilometres away.

Contrary to Swiss watch brands, which keep their master craftsmen under wraps, Grand Seiko and Credor proudly recognise their star employees publicly. One of those prized team members is Masatoshi Moteki, a 27-year employee of Seiko who spent six years working with the development team for the Spring Drive movement before becoming an elite craftsman at the Micro Artist Studio. Alongside studio leader Kenji Shiohara, Moteki developed a minute repeater and sonnerie that incorporated the brands’ Spring Drive movement and are unlike anything else on the market. Because the Spring Drive is a silent mechanism, it allows for greater sound quality in the other complications.

The clean, lingering sound in the minute repeater is achieved by two types of hammers striking two steel gongs, typical of sound-producing timepieces, but in this case made from a special steel by Munemichi Myochin, a craftsman from an ancient Japanese family that has been forging steel for 850 years. The sound produced by the gongs, says Moteki, “takes inspiration from Japanese wind chimes made by Myochin—the very comforting, relaxing sound of the summer wind”.

The sonnerie derives its ring from the big, strong gongs of Japanese temples, known as Orin bells. The micro re-creations of this ancient Japanese form of telling time produce sound with three seconds between each ring. “It is three because after the sound disappears there is a slight moment of silence, and that idea is inspired by traditional Japanese poems,” says

Moteki. “It’s similar to the sound water drops make as they slowly dissipate. That quality relates to the philosophy of the Spring Drive movement also—it’s a very calm, aesthetic motion.”

The Micro Artist Studio was founded two decades ago, with the first Credor sonnerie debuting in 2006 and the minute repeater in 2011. But in the early days, Moteki admits he and his colleagues didn’t know anything about making grand complications; most people in the company had never even heard the term “minute repeater”. The complication has been around in Europe since the mid-18th century. “I tried to persuade my boss about doing these high-level movements, and it was difficult,” says Moteki with a jolly demeanour that belies his genius. “But one day he saw a TV program where a local Nagano collector was showing his watches, one of which was a pocket-watch minute repeater. Then my boss wanted to do one, but he didn’t understand how difficult it is to develop. We were very behind.” That’s an understatement. Jean-Claude Biver, a connoisseur and the former president of LVMH’s watch division, once likened creating a minute repeater to climbing Mount Everest. Catching up would prove hard work.

When asked how he and the team learned to produce watchmaking’s most intricate complications in less than 20 years, Moteki turns to an old bookshelf and grabs a stack of watchmaking tomes written in English. Standing proudly in the centre of the small studio, he throws them on the table to suggest he simply read how to do it. He and the team are self-taught. Watchmakers in Switzerland spend years, often decades, apprenticing under masters to acquire the skills necessary to create minute repeaters.

Lest you think that means Credor’s quality is at all inferior, the work of Moteki and his colleagues was praised by Philippe Dufour, one of Swiss watchmaking’s most revered figures, who came to see the studio after hearing about their creations. A signed, framed photo of Dufour hangs there now. Dufour, already impressed with their technical know-how, lent a little expertise in aesthetic excellence. The Micro Artist Studio had previously finished the cases by machine; the artisans hadn’t known how to polish the movements by hand.

“Mr Dufour told me about the use of the gentian plant, but all he told me was that it is hard outside and soft inside, so we tried to find something similar in Japan,” says Moteki. “We looked for a long time.” (Gentian is a herbal plant that grows in the hills of Switzerland and is used for finishing watch movements in the Alps’ best ateliers, Greubel Forsey and Blancpain among them.) Moteki eventually discovered that a university in Hokkaido was growing the plant for medicinal studies—and was willing to share, allowing the Credor team to create movements on par with their elite Swiss counterparts.

The Japanese are not intimidated by the head start enjoyed by the Europeans. “Of course, we have high respect for the Swiss watchmakers,” says Seiko’s Takahashi. “They have their philosophy and their style, but we are from Japan, and our sense of nature has been fostered over many, many centuries in this country.”

This piece is from our new Design Issue – on sale now. Get your copy or subscribe here, or stay up to speed with the Robb Report weekly newsletter.

Subscribe to the Newsletter

Recommended for you

Omega Reveals a New Speedmaster Ahead of the Paris 2024 Olympics

Your first look at the new Speedmaster Chronoscope, designed in the colour theme of the Paris Olympics.

By Josh Bozin

April 26, 2024

Watch of the Week: the Piaget Altiplano Ultimate Concept Tourbillon

The new release claims the throne as the world’s thinnest Tourbillon.

By Josh Bozin

April 19, 2024

You may also like.

You may also like.

Omega Reveals a New Speedmaster Ahead of the Paris 2024 Olympics

Your first look at the new Speedmaster Chronoscope, designed in the colour theme of the Paris Olympics.

The starters are on the blocks, and with less than 100 days to go until the Paris 2024 Olympics, luxury Swiss watchmaker Omega was bound to release something spectacular to mark its bragging rights as the official timekeeper for the Summer Games. Enter the new 43mm Speedmaster Chronoscope, available in new colourways—gold, black, and white—in line with the colour theme of the Olympic Games in Paris this July.

So, what do we get in this nicely-wrapped, Olympics-inspired package? Technically, four new podium-worthy iterations of the iconic Speedmaster.

The new versions present handsomely in stainless steel or 18K Moonshine Gold—the brand’s proprietary yellow gold known for its enduring shine. The steel version comes with an anodised aluminium bezel and a stainless steel bracelet or vintage-inspired perforated leather strap. The Moonshine Gold iteration boasts a ceramic bezel, and will most likely appease Speedy collectors, particularly those with an affinity for Omega’s long-standing role as stewards of the Olympic Games, since 1932.

Notably, each watch bears an attractive white opaline dial; the background to three dark grey timing scales in a 1940s “snail” design. Of course, this Speedmaster Chronoscope is special in its own right. For the most part, the overall look of the Speedmaster has remained true to its 1957 origins. This Speedmaster, however, adopts Omega’s Chronoscope design from 2021, including the storied tachymeter scale, along with a telemeter, and pulsometer scale—essentially, three different measurements on the wrist.

While the technical nature of this timepiece won’t interest some, others will revel in its theatrics; turn over each timepiece and instead of finding a transparent crystal caseback, there is a stamped medallion featuring a mirror-polished Paris 2024 logo, along with “Paris 2024” and the Olympic Rings—a subtle nod to this year’s games.

Powering this Olympiad offering—and ensuring the greatest level of accuracy—is the Co-Axial Master Chronometer Calibre 9908 and 9909, certified by METAS.

A Speedmaster to commemorate the Olympic Games was as sure a bet as Mondo Deplatntis winning gold in the men’s pole vault—especially after Omega revealed its Olympic-edition Seamaster Diver 300m “Paris 2024” last year—but they have delivered a great addition to the legacy collection, without gimmickry.

However, at the top end of the scale, you’re looking at 85K for the all-gold Speedmaster, which is a lot of money for a watch of this stature. In comparison, the immaculate Speedmaster Moonshine gold with a sun-brushed green PVD “step” dial is 15K cheaper, albeit without the Chronoscope complications.

—

The Omega Speedmaster Chronoscope in stainless steel with a leather strap is priced at $15,725; stainless steel with steel bracelet at $16,275; 18k Moonshine Gold on leather strap $54,325; and 18k Moonshine Gold with matching gold bracelet $85,350, available at Omega boutiques now.

Discover the collection here

You may also like.

Here’s What Goes Into Making Jay-Z’s $1,800 Champagne

We put Armand de Brignac Blanc de Noirs Assemblage No. 4 under the microsope.

In our quest to locate the most exclusive and exciting wines for our readers, we usually ask the question, “How many bottles of this were made?” Often, we get a general response based on an annual average, although many Champagne houses simply respond, “We do not wish to communicate our quantities.” As far as we’re concerned, that’s pretty much like pleading the Fifth on the witness stand; yes, you’re not incriminating yourself, but anyone paying attention knows you’re probably guilty of something. In the case of some Champagne houses, that something is making a whole lot of bottles—millions of them—while creating an illusion of rarity.

We received the exact opposite reply regarding Armand de Brignac Blanc de Noirs Assemblage No. 4. Yasmin Allen, the company’s president and CEO, told us only 7,328 bottles would be released of this Pinot Noir offering. It’s good to know that with a sticker price of around $1,800, it’s highly limited, but it still makes one wonder what’s so exceptional about it.

Known by its nickname, Ace of Spades, for its distinctive and decorative metallic packaging, Armand de Brignac is owned by Louis Vuitton Moët Hennessy and Jay-Z and is produced by Champagne Cattier. Each bottle of Assemblage No. 4 is numbered; a small plate on the back reads “Assemblage Four, [X,XXX]/7,328, Disgorged: 20 April, 2023.” Prior to disgorgement, it spent seven years in the bottle on lees after primary fermentation mostly in stainless steel with a small amount in concrete. That’s the longest of the house’s Champagnes spent on the lees, but Allen says the winemaking team tasted along the way and would have disgorged earlier than planned if they’d felt the time was right.

Chef de cave, Alexandre Cattier, says the wine is sourced from some of the best Premier and Grand Cru Pinot Noir–producing villages in the Champagne region, including Chigny-les-Roses, Verzenay, Rilly-la-Montagne, Verzy, Ludes, Mailly-Champagne, and Ville-sur-Arce in the Aube département. This is considered a multi-vintage expression, using wine from a consecutive trio of vintages—2013, 2014, and 2015—to create an “intense and rich” blend. Seventy percent of the offering is from 2015 (hailed as one of the finest vintages in recent memory), with 15 percent each from the other two years.

This precisely crafted Champagne uses only the tête de cuvée juice, a highly selective extraction process. As Allen points out, “the winemakers solely take the first and freshest portion of the gentle cuvée grape press,” which assures that the finished wine will be the highest quality. Armand de Brignac used grapes from various sites and three different vintages so the final product would reflect the house signature style. This is the fourth release in a series that began with Assemblage No. 1. “Testing different levels of intensity of aromas with the balance of red and dark fruits has been a guiding principle between the Blanc de Noirs that followed,” Allen explains.

The CEO recommends allowing the Assemblage No. 4 to linger in your glass for a while, telling us, “Your palette will go on a journey, evolving from one incredible aroma to the next as the wine warms in your glass where it will open up to an extraordinary length.” We found it to have a gorgeous bouquet of raspberry and Mission fig with hints of river rock; as it opened, notes of toasted almond and just-baked brioche became noticeable. With striking acidity and a vein of minerality, it has luscious nectarine, passion fruit, candied orange peel, and red plum flavors with touches of beeswax and a whiff of baking spices on the enduring finish. We enjoyed our bottle with a roast chicken rubbed with butter and herbes de Provence and savored the final, extremely rare sip with a bit of Stilton. Unfortunately, the pairing possibilities are not infinite with this release; there are only 7,327 more ways to enjoy yours.

You may also like.

Bill Henson Show Opens at Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery

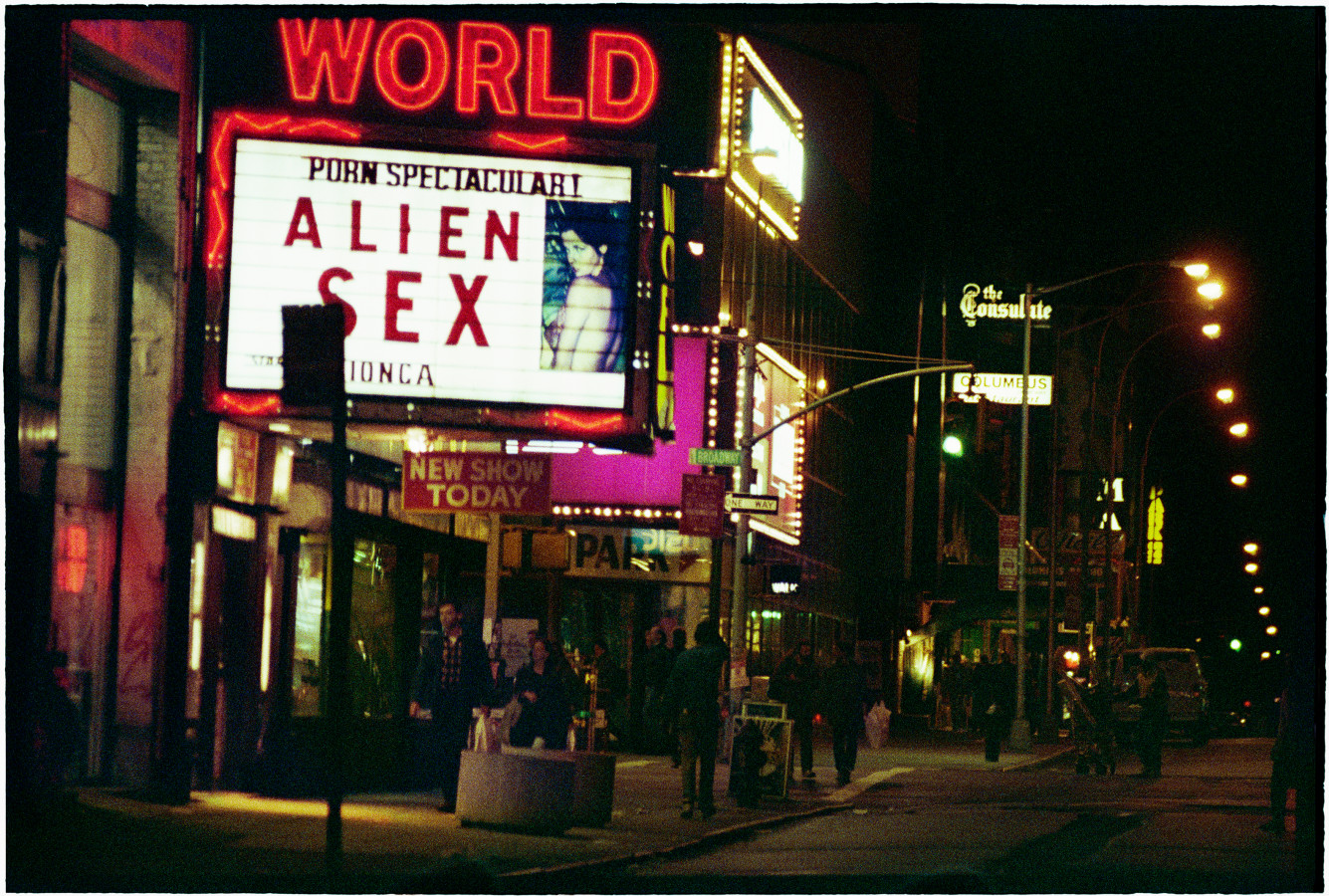

Dark, grainy and full of shadows Bill Henson’s latest show draws on 35 mm colour film shot in New York City in 1989.

Bill Henson is one of Australia’s best-known contemporary photographers. When a show by this calibre of artist opens here, the art world waits with bated breath to see what he will unveil.

This time, he presents a historically important landscape series that chronicles a time in New York City that no longer exists. It’s a nostalgic trip back in time, a nocturnal odyssey through the frenetic, neon-lit streets of a long-lost America.

Known for his chiaroscuro style, Henson’s cinematic photographs often transform his subject into ambiguous objects of beauty. This time round, the show presents a mysterious walk through the streets of Manhattan, evoking a seedy, yet beautiful vision of the city.

Relying on generative gaps, these landscapes result from Henson mining his archive of negatives and manipulating them to produce a finished print. Sometimes, they are composed by a principle of magnification, with Henson honing in on details, and sometimes, they are created through areas of black being expanded to make the scene more cinematic and foreboding. Like silence in a film or the pause in a pulse, the black suggests the things you can’t see.

Henson’s illustrious career has spanned four decades and was memorably marred by controversy over a series of nude adolescent photographs shown in 2008, which made him front-page news for weeks. This series of portraits made Henson the subject of a police investigation during which no offence was found.

In recent years, Henson has been a sharp critic of cancel culture, encouraging artists to contribute something that will have lasting value and add to the conversation, rather than tearing down the past.

His work deals with the liminal space between the mystical and the real, the seen and unseen, the boundary between youth and adulthood.

His famous Paris Opera Project, 1990-91, pictured above, is similarly intense as the current show, dwelling on the border between the painterly and the cinematic.

Bill Henson’s ‘The Liquid Night’ runs until 11 May 2024 at Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery.

Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, 8 Soudan Ln, Paddington NSW; roslynoxley9.com.au

You may also like.

Polar Opposites

A journey north to one of the harshest, remotest spots on Earth couldn’t be more luxurious.

A century ago, an expedition to the North Pole involved dog sleds and explorers in heavy, fur-lined clothes, windburned and famished after weeks of trudging across ice floes, finally planting their nations’ flags in the barren landscape. These days, if you’re a tourist, the only way to reach 90 degrees north latitude, the geographic North Pole, is aboard Le Commandant Charcot, a six-star hotel mated to a massive, 150-metre ice-breaking hull.

My wife, Cathy, and I are among the first group of tourists aboard Ponant’s new expedition icebreaker, the world’s only Polar Class 2–rated cruise ship (of seven levels of ice vessel, second only to research and military vessels in ability to manoeuvre in Arctic conditions). Our arrival on July 14 couldn’t be more different from explorer Robert Peary’s on April 6, 1909. On that date, he reported, he staked a small American flag—sewed by his wife—into the Pole, joined by four Inuits and his assistant, Matthew Henson, a Black explorer from Maine who was with Peary on his two previous Arctic expeditions. (Peary’s claim of being first to the Pole was quickly disputed by another American, Frederick Cook, who insisted he’d spent two days there a year earlier. Scholars now view both claims with skepticism.)

Our 300-plus party’s landing, on Bastille Day, features the captain of the French ship driving around in an all-terrain vehicle with massive wheels and an enormous tricolour flag on the back, guests dressed in stylish orange parkas celebrating on the ice, and La Marseillaise, France’s national anthem, blaring from loudspeakers. After an hour of taking selfies and building snow igloos in the icescape, with temperatures in the relatively balmy low 30s, we head back into our heated sanctuary for mulled wine and freshly baked croissants. Mission accomplished. Flags planted. Now, lunch.

As a kid, I was fascinated by stories of adventurers trying to reach the North Pole without any means of rescue. In the 19th century, most of their attempts ended in disaster—ships getting trapped in the ice, a hydrogen balloon crashing, even cannibalism. It wasn’t until Cook and Peary reportedly set foot there that the race to the North Pole was really on. Norwegian Roald Amundsen, the first to reach the South Pole, in 1911, is credited with being the first to document a trip over the North Pole, which he did in 1926 in the airship Norge. In 1977, the nuclear-powered icebreaker Arktika became the first surface vessel to make it to the North Pole. Since then, only 18 other ships have completed the voyage.

Visiting the North Pole seemed about as likely for me as walking on the Moon. It wasn’t even on my bucket list. Then came Le Commandant Charcot, which was named after France’s most beloved polar explorer and reportedly cost about US$430 million (around $655 million) to build. The irony of visiting one of the planet’s most remote and inhospitable points while travelling in the lap of luxury doesn’t escape me or anyone else I speak with on the voyage. Danie Ferreira, from Cape Town, South Africa, describes it as “an ensemble of contradictions bordering on the absurd”. Ferreira, who is on board with his wife, Suzette, is a veteran of early-explorer-style high-Arctic journeys, months-long treks involving dog sleds and real toil and suffering. He booked this trip to obtain an official North Pole stamp for an upcoming two-volume collection of his photographs, Out in the Cold, documenting his polar adventures. “Reserving the cabin felt like a betrayal of my expeditionary philosophy,” he says with a laugh.

Then, like the rest of us, he embraces the contradictions. “This is like the first time I saw the raw artistry of Cirque du Soleil,” he explains. “Everything is beyond my wildest expectations, unrelatable to anything I’ve experienced.”

The 17-day itinerary launches from the Norwegian settlement of Longyearbyen, Svalbard, the northernmost town in the Arctic Circle, and heads 1,186 nautical miles to the North Pole, then back again. As a floating hotel, the vessel is exceptional: 123 balconied staterooms and suites, the most expensive among them duplexes with butler service (prices range from around $58,000 to $136,000 per person, double occupancy); a spa with a sauna, massage therapists, and aestheticians; a gym and heated indoor pool. The boat weighs more than 35,000 tons, enabling it to break ice floes like “a chocolate bar into little pieces, rather than slice through them”, according to Captain Patrick Marchesseau. Six-metre-wide stainless-steel propellers, he adds, were designed to “chew ice like a blender”.

Marchesseau, a tall, lanky, 40-ish mariner from Brittany, impeccable in his navy uniform but rocking royal-blue boat shoes, proves to be a charming host. Never short of a good quip, he’s one of three experienced ice captains who alternate at the helm of Charcot throughout the year. He began piloting Ponant ships through drifting ice floes in Antarctica in 2009, when he took the helm of Le Diamant, Ponant’s first expedition vessel. “An epic introduction,” Marchesseau calls those early voyages, but the isolated, icebound North Pole aboard a larger, more complicated vessel is potentially an even thornier challenge. “We’ll first sail east where the ice is less concentrated and then enter the pack at 81 degrees,” he tells a lecture hall filled with passengers on day one. “We don’t plan to stop until we get to the North Pole.”

Around us, the majority of the other 101 guests are older French couples; there are also a few extended families, some other Europeans, mostly German and Dutch, as well as 10 Americans. Among the supporting cast are six research scientists and 221 staff, including 18 naturalist guides from a variety of countries.

The first six days are more about the journey than the destination. Cathy and I settle into our comfortable stateroom, enjoy the ocean views from our balcony, make friends with other guests and naturalists, frequent the spa, and indulge in the contemporary French cuisine at Nuna, which is often jarred by ice passing under the hull, as well as at the more casual Sila (Inuit for “sky”). There are the usual cruise events: the officers’ gala, wine pairings, daily French pastries, Broadway-style shows, opera singers and concert pianists. Initially, I worry about “Groundhog Day” setting in, but once we hit patchy ice floes on day two, it’s clear that the polar party is on. The next day, we’re ensconced in the ice pack.

Veterans of Arctic journeys immediately feel at home. Ferreira, often found on the observation deck 15 metres above the ice with his long-lensed cameras, is in his element snapping different patterns and colours of the frozen landscape. “It feels like combining low-level flying with an out-of-body experience,” he says. “Whenever the hull shudders against the ice, I have a reality check.”

“I came back because I love this ice,” adds American Gin Millsap, who with her husband, Jim, visited the North Pole in 2015 aboard the Russian nuclear icebreaker Fifty Years of Victory, which for obvious reasons is no longer a viable option for Americans and many Europeans. “I love the peace, beauty and calmness.”

It is easy to bliss out on the endless barren vistas, constantly morphing into new shapes, contours and shades of white as the weather moves from bright sunshine to howling snowstorms—sometimes within the course of a few hours. I spend a lot of time on the cold, windswept bow, looking at the snow patterns, ridges and rivers flowing within the pale landscape as the boat crunches through the ice. It feels like being in a black-and-white movie, with no colours except the turquoise bottoms of ice blocks overturned by the boat. Beautiful, lonely, mesmerising.

Rather than a solid landmass, the Arctic ice pack is actually millions of square kilometres of ice floes, slowly pushed around by wind and currents. The size varies according to season: this past winter, the ice was at its fifth-lowest level on record, encompassing 14.6 million square kilometres, while during our cruise it was 4.7 million square kilometres, the 10th-lowest summer number on record. There are myriad ice types—young ice, pancake ice, ice cake, brash ice, fast ice—but the two that our ice pilot, Geir-Martin Leinebø, cares about are first-year ice and old ice. The thinness of the former provides the ideal route to the Pole, while the denseness of the aged variety can result in three-to-eight-metre-high ridges that are potentially impassable. Leinebø is no novice: in his day job, he’s the captain of Norway’s naval icebreaker, KV Svalbard, the first Norwegian vessel to reach the North Pole, in 2019.

It’s not a matter of just pointing the boat due north and firing up the engine. Leinebø zigzags through the floes. A morning satellite feed and special software aid in determining the best route; the ship’s helicopter sometimes scouts 65 or so kilometres ahead, and there’s a sonar called the Sea Ice Monitoring System (SIMS). But mostly Leinebø uses his eyes. “You look for the weakest parts of the ice—you avoid the ridges because that means thickness and instead look for water,” he says. “If the ‘water sky’ in the distance is dark, it’s reflecting water like a mirror, so you head in that direction.”

Everyone on the bridge is surprised by the lack of multi-year ice, but with more than a hint of disquietude. Though we don’t have to ram our way through frozen ridges, the advance of climate change couldn’t be more apparent. Environmentalists call the Arctic ice sheet the canary in the coal mine of the planet’s climate change for good reason: it is happening here first. “It’s not right,” mutters Leinebø. “There’s just too much open water for July. Really scary.”

The Arctic ice sheet has shrunk to about half its 1985 size, and as both mariners and scientists on board note, the quality of the ice is deteriorating. “It’s happening faster than our models predicted,” says Marisol Maddox, senior arctic analyst at the Polar Institute of the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars. “We’re seeing major events like Greenland’s ice sheet melting and sliding into the ocean—that wasn’t forecasted until 2070.” The consensus had been that the Arctic would be ice-free by 2050, but many scientists now expect that day to come in the 2030s.

That deterioration, it turns out, is why the three teams of scientists are on the voyage—two studying the ice and the other assessing climate change’s impact on plankton. As part of its commitment to sustainability, Ponant has designed two research labs—one wet and one dry—on a lower deck. “We took the advice of many scientists for equipping these labs,” says Hugues Decamus, Charcot’s chief engineer, clearly proud of the nearly US$12 million facilities.

The combined size of the labs, along with a sonar room, a dedicated server for the scientists, and a meteorological station on the vessel’s top deck, totals 130 square metres—space that could have been used for revenue generation. Ponant also has two staterooms reserved for scientists on each voyage and provides grants for travel expenses. The line doesn’t cherrypick researchers but instead asks the independent Arctic Research Icebreaker Consortium (ARICE) to choose participants based on submissions.

The idea, says the vessel’s science officer on this voyage, Daphné Buiron, is to make the process transparent and minimise the appearance of greenwashing. “Yes, this alliance may deliver a positive public image for the company, but this ship shows we do real science on board,” she says. The labs will improve over time, adds Decamus, as the ship amasses more sophisticated equipment.

Research scientists and tourist vessels don’t typically mix. The former, wary of becoming mascots for the cruise lines’ sustainability marketing efforts, and cognisant of the less-than-pristine footprint of many vessels, tend to be wary. The cruise lines, for their part, see scientists as potentially high maintenance when paying customers should be the priority. But there seemed to be a meeting of the minds, or at least a détente, on Le Commandant Charcot.

“We discuss this a lot and are aware of the downsides, but also the positives,” says Franz von Bock und Polach, head of the institute for ship structural design and analysis at Hamburg University of Technology, specialising in the physics of sea ice. Not only does Charcot grant free access to these remote areas, but the ship will also collect data on the same route multiple times a year with equipment his team leaves on board, offering what scientists prize most: repeatability. “One transit doesn’t have much value,” he says. “But when you measure different seasons, regions and years, you build up a more complex picture.” So, more than just a research paper: forecasts of ice conditions for long-term planning by governments as the Arctic transforms.

Nils Haëntjens, from the University of Maine, is analysing five-millilitre drops of water on a high-tech McLane IFCB microscope. “The instrument captures more than 250,000 images of phytoplankton along the latitudinal transect,” he says. Charcot has doors in the wet lab that allow the scientists to take water samples, and in the bow, inlets take in water without contaminating it. Two freezers can preserve samples for further research back in university labs.

Even though the boat won’t stop, the captain and chief engineer clearly want to make the science missions work. Marchesseau dispatches the helicopter with the researchers and their gear 100 kilometres ahead, where they take core samples and measurements. I spot them in their red snowsuits, pulling sleds on an ice floe, as the boat passes. Startled to see living-colour humans on the ice after days of monochrome, I feel a pang of jealousy as I head for a caviar tasting.

The only other humans we encounter on the journey north are aboard Fifty Years of Victory, the Russian icebreaker. The 160-metre orange- and-black leviathan reached the North Pole a day earlier—its 59th visit—and is on its way back to Murmansk. It’s a classic East meets West moment: the icebreaker, launched just after the collapse of the Soviet Union, meeting the new standard of polar luxury.

The evening before Bastille Day, Le Commandant Charcot arrives at the North Pole. Because of the pinpoint precision of the GPS, Marchesseau has to navigate back and forth for about 20 minutes—with a bridge full of passengers hushing each other so as not to distract him—until he finds 90 degrees north. That final chaotic approach to the top of the world in the grey, windswept landscape looks like a kid’s Etch A Sketch on the chartplotter, but it is met with rousing cheers. The next morning, with good visibility and light winds, we spill out onto the ice for the celebration, followed by a polar plunge.

As guests pose in front of flags and mile markers for major cities, the naturalist guides, armed with rifles, establish a wide perimeter to guard against polar bears. The fearless creatures are highly intelligent, with razor-sharp teeth, hooked claws and the ability to sprint at 40 km/h. Males average about three metres tall and weigh around 700 kilos. They are loners that will kill anything—including other bears and even their own cubs. Cathy and I walk around the far edges of the perimeter to enjoy some solitude. Looking out over the white landscape, I know this is a milestone. But it feels odd that getting here didn’t involve any sweat or even a modicum of discomfort.

The rest of the week is an entirely different trip. On the return south, we see a huge male polar bear ambling on the ice, looking over his shoulder at us. It is our first sighting of the Arctic’s apex predator, and everyone crowds the observation lounge with long-lensed cameras. The next day, we see another male, this one smaller, running away from the ship. “They have many personalities,” says Steiner Aksnes, head of the expedition team, who has led scientists and film crews in the Arctic for 25 years. We see a dozen on the return to Svalbard, where 3,000 are scattered across the archipelago, outnumbering human residents.

The last five days we make six stops on different islands, travelling by Zodiac from Charcot to various beaches. On Lomfjorden, as we look on a hundred yards from shore, a mother polar bear protects her two cubs while a young male hovers in the background. On a Zodiac ride off Alkefjellet, the air is alive with birds, including tens of thousands of Brünnich’s guillemots as well as glaucous gulls and kittiwakes, which nest in that island’s cliffs, while a young male polar bear munches on a ring seal, chin glistening red.

On this part of the trip, the expedition team, mostly 30-something, free-spirited scientists whose areas of expertise range from botany to alpine trekking to whales, lead hikes across different landscapes. The jam-packed schedule sometimes involves three activities per day and includes following the reindeer on Palanderbukta, seeing a colony of 200 walruses on Kapp Lee, hiking the black tundra of Burgerbukta (boasting 3.8-cm-tall willows—said to be the smallest trees in the world and the largest on Svalbard—plus mosquitoes!), watching multiple species of whales breaching offshore, and kayaking the ice floes of Ekmanfjorden. Svalbard is a protected wilderness area, and the cruise lines tailor their schedules so vessels don’t overlap, giving visitors the impression they are setting foot on virgin land.

Chances to experience that sense of discovery and wonder, even slightly stage-managed ones, are dwindling along with the ice sheet and endangered wildlife. If a stunning trip to a frozen North Pole is on your bucket list, the time to go is now.

PARADIGM SHIP

For those studying polar ice, a berth aboard Le Commandant Charcot is like a winning lottery ticket. “This cruise ship is one of the few resources scientists can use, because nothing else can get there,” says G. Mark Miller, CEO of research-vessel builder Greenwater Marine Sciences Offshore (GMSO) and a former ship captain for the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). “Then factor in 80 percent of scientists who want to go to sea, can’t, because of the shortage of research vessels.”

Both Ponant and Viking have designed research labs aboard new expedition vessels as part of their sustainability initiatives. “Remote areas like Antarctica need more data—the typical research is just single data points,” says Damon Stanwell-Smith, Ph.D., head of science and sustainability at Viking. “Every scientist says more information is needed.” The twin sisterships Viking Octantis and Viking Polaris, which travel to Antarctica, Patagonia, the Great Lakes and Canada, have identical 35-square-metre labs, separated into wet and dry areas and fitted out with research equipment. In hangars below are military-grade rigid-hulled inflatables and two six-person yellow submersibles (the pair on Octantis are named John and Paul, while Polaris’s are George and Ringo). Unlike Ponant, Viking doesn’t have an independent association choose scientists for each voyage. Instead, it partners with the University of Cambridge, the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, and NOAA, which send their researchers to work with Viking’s onboard science officers.

“Some people think marine research is sticking some kids on a ship to take measurements,” says Stanwell-Smith. “But we know we can do first-rate science—not spin.” Other cruise lines are also embracing sustainability initiatives, with coral-reef-restoration projects and water-quality measurements, usually in partnership with universities. Just about every vessel has “citizen-scientist” research programs allowing guests the opportunity to count birds or pick up discarded plastic on beaches. So far, Ponant and Viking are the only lines with serious research labs. Ponant is adding science officers to other vessels in its fleet. As part of the initiatives, scientists deliver onboard lectures and sometimes invite passengers to assist in their research.

Given the shortage of research vessels, Stanwell-Smith thinks this passenger-funded system will coexist nicely with current NGO- and government-owned ships. “This could be a new paradigm for exploring the sea,” he says. “Maybe the next generation of research vessels will look like ours.”

You may also like.

Watch of the Week: the Piaget Altiplano Ultimate Concept Tourbillon

The new release claims the throne as the world’s thinnest Tourbillon.

Piaget, the watchmaker’s watchmaker, has once again redefined the meaning of “ultra-thin” thanks to its newest masterpiece, the Altiplano Ultimate Concept Tourbillon—the world’s thinnest tourbillon watch.

In the world of high-watchmaking where thin is never thin enough—look at the ongoing battle between Piaget, Bulgari, and Richard Mille for the honours—Piaget caused a furore at Watches & Wonders in Geneva when it unveiled its latest feat to coincide with the Maison’s 150th year anniversary.

Piaget claims that the new Altiplano is “shaped by a quest for elegance and driven by inventiveness”, and while this might be true, it’s clear that the Maison’s high-watchmaking divisions in La Côte-aux-Fées and Geneva are also looking to end the conversation around who owns the ultra-thin watchmaking category.

The new Altiplano pushes the boundaries of horological ingenuity 67 years after Piaget invented its first ultra-thin calibre—the revered 9P—and six years after it presented the world’s then-thinnest watch, the Altiplano Ultimate Concept. Now, with the release of this unrivalled timepiece at just 2mm thick—the same as its predecessor, yet now housing the beat of a flying tourbillon, prized by watchmaking connoisseurs—you can’t help but marvel at its ultra-thin mastery, whether the timepiece is to your liking or not.

In comparison, the Bulgari Octo Finissimo Tourbillon was 3.95mm thick when unveiled in 2020, which seems huge on paper compared to what Piaget has been able to produce. But to craft a watch as thin and groundbreaking as its predecessor, now with an added flying tourbillon complication, the whole watchmaking process had to be revalued and reinvented.

“We did far more than merely add a tourbillon,” says Benjamin Comar, Piaget CEO. “We reinvented everything.”

After three years of R&D, trial and error—and a redesign of 90 percent of the original Altiplano Ultimate Concept components—the 2024 version needs to be held and seen to be believed. The end product certainly isn’t a watch for the everyday watch wearer—although Piaget will tell you otherwise—but in many ways, the company didn’t conjure a timepiece like the Altiplano as a profit-seeking exercise. Instead, overcoming such an arduous and technical watchmaking feat proves that Piaget can master the flying tourbillon in such a whimsical fashion and, in the process, subvert the current state-of-the-art technical principles by making an impactful visual—and technical—statement.

The only question left to ask is, what’s next, Piaget?

—

Model: Altiplano Ultimate Concept Tourbillon 150th Anniversary

Diameter: 41.5 mm

Thickness: 2 mm (crystal included)

Material: M64BC cobalt alloy, blue PVD -treated

Dial: Monobloc dial; polished round and baton indices, Bâton-shaped hand for the minutes Monobloc disc with a hand for the hours

Water resistance: 20m

Movement: Calibre 970P-UC, one-minute peripheral tourbillon

Winding: Hand-wound

Functions: hours, minutes, and small seconds (time-only)

Power reserve: 40 hours

Availability: Limited production, not numbered

Price: Price on request