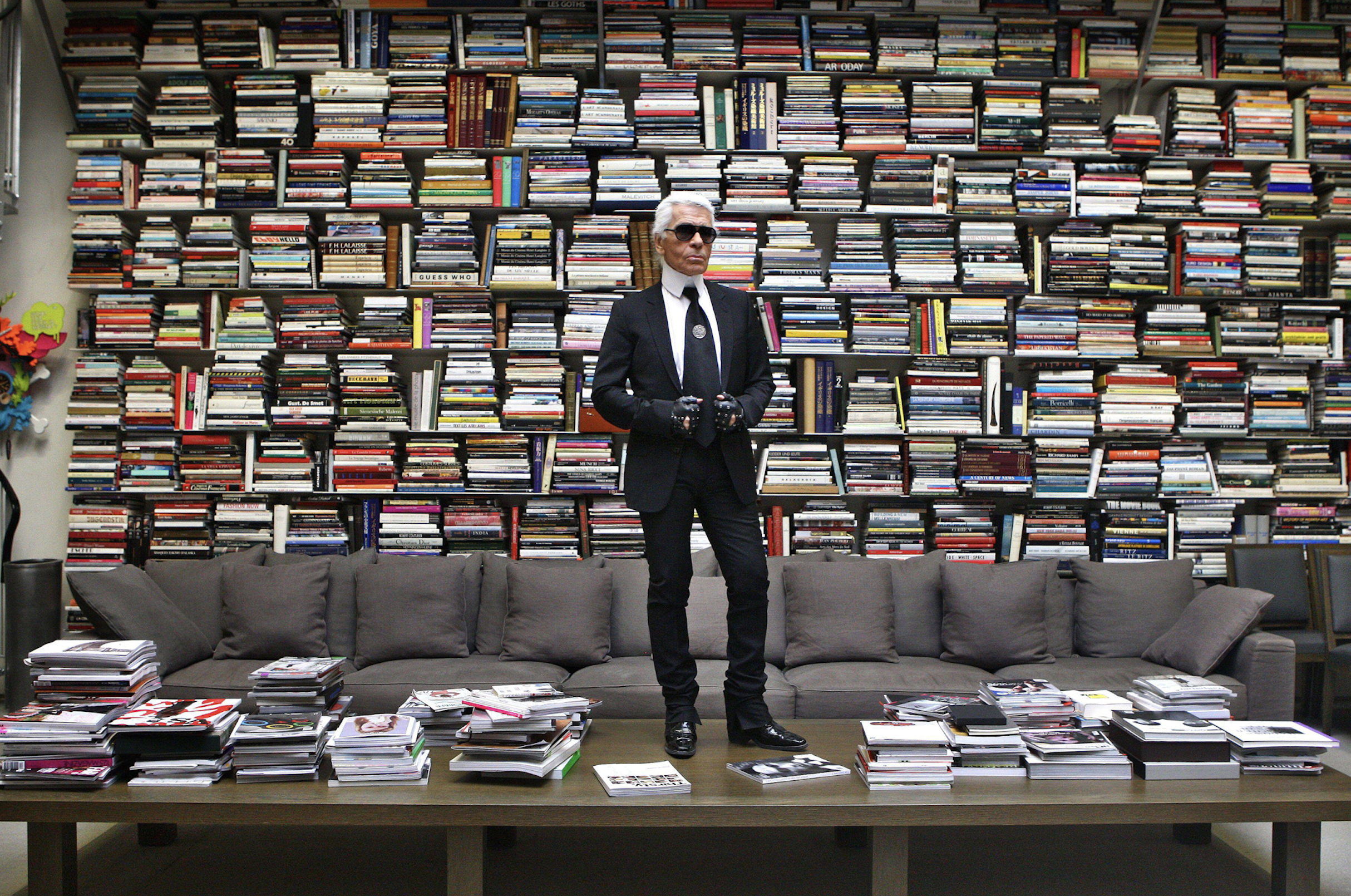

Robb Interview: Jesse Marlow

An award-winning Australian ‘street’ photographer, Marlow explores his new book, Melbourne’s lost grit and learning to be creative during COVID.

Related articles

Robb Report: ‘Second City’ is your impressive new book — talk us through the title and the narrative such sets out; does this play to the notion of the ‘unseen city’, that is, the ‘unremarkable’ city and those unnoticed occurrences of the everyday?

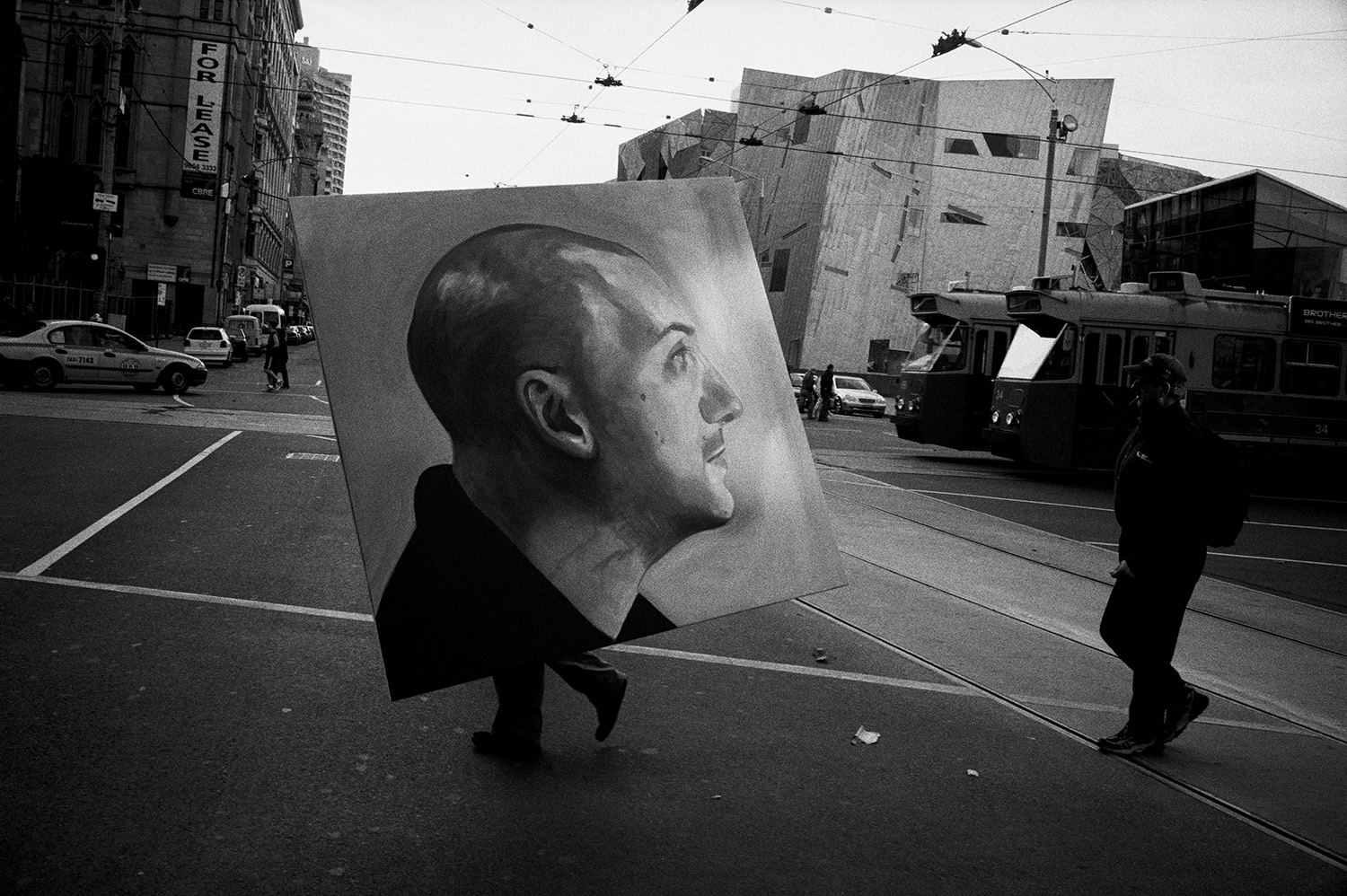

Jesse Marlow: Yes and No. Initially the term ‘Second City’ came to mind because of the constant reference to Melbourne (in regards to Sydney) as Australia’s ‘Second City’ during the initial Covid-19 reporting. The title took on a whole new meaning when I was editing the photo’s and reflecting on the major changes Melbourne has undergone over the past 20-25 years. From the desolate streets to the now bustling metropolis, the title has come to encompass the fact that the photographs show a whole different side of a well-known city. As someone whose lived here my whole life, there’s always an unknown or long forgotten side to a city to discover or rediscover.

RR: The period captured here, the late ‘90s and into the new millennium — what are your memories from that time?

JM: It wasn’t until the early 2000’s that the CBD seemed to really awaken. With the onset of apartment living, the unique laneways began to be utilised with cafes and bars starting to pop up in innovative spots. As a young photographer discovering the ins and outs of my hometown, I would wander the streets, often in awe of the characters and subcultures, I’d encounter. There was an edge and an element of grit to the city and its people. Older men in three-piece suits and hats; young punks and old drunks. You’d walk around the city and there was an abundance of characters you’d come across on a daily basis. The city and its urban planning hadn’t been as refined as it is today — thugs weren’t as structured and clean as they now seem. The simple things in the city brought me inspiration — sitting on the steps under the clocks at Flinders St Station watching on, camera in hand, as people started moving in and out of the station.

RR: As you say, Melbourne as a city has certainly grown-up a lot since then. Do you miss what was perhaps a sense of innocence that existed back then?

JM: I miss the edginess and gritty feel to the city. As many of the characters and unique independent shops have long disappeared from the city streets, I feel like the city has lost some of the identity that gave it its character and edge.

RR: In curating and selecting images, how many photos did you pore over to form this collection and how do you find that process — what are the emotions attached to going back through older works and re-viewing things?

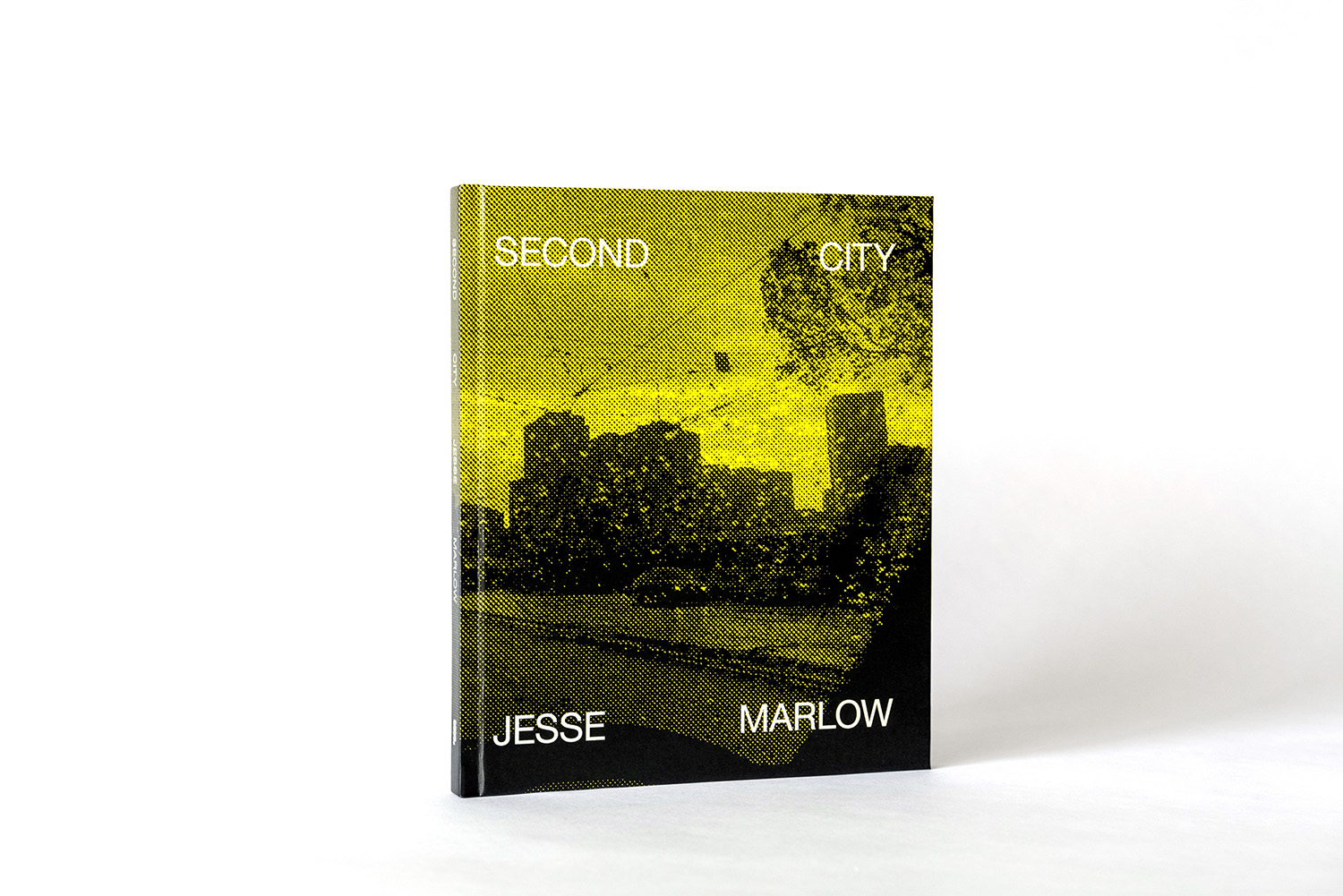

JM: The body of work had sat dormant for the last 15 years, and the idea was always to present it as a book, the only question being ‘when’? I’m one of those people that isn’t very good at slowing down, so during lockdown last year, having a forced hiatus from commercial work, I had to do something with my time, so going back through older work seemed like a good option. It turned out to be a really productive time to work on projects that I’d never finished or had put on the back burner. I’ve produced four books over the years, and they all come with their own unique challenges. Books have always been my preferred way of showing my work in a longer form. Unlike an exhibition, which can be up for a few weeks and only seen by a small audience, the potential reach of a book excites me.

RR: Why monochrome – what does it offer over the presentation of colour?

JM: The photos began while I was at photography school and one of the main features of the TAFE course I signed up for was the allure of unlimited B&W film. This meant bulk loading film, storing it in my fridge at home and heading into the city on a daily basis.

In my first year at photography school, I actually failed the course due to a lack of attendance as I spent most of the time in the city shooting some of the work featured in the book. The irony is, whilst I failed the year, I also managed to win the award for ‘Most Film Used in a Year’. I had also been studying the work of some of the masters – Henri Cartier-Bresson, Josef Koudelka and Garry Winogrand, who’d all shot candid B&W work, so shooting in monochrome seemed like the logical pathway into documenting the world around me.

RR: You sometimes appear as a shadow or a reflection in your images. Where many photographers aim to avoid such, why are you seemingly happy to be captured, however minor?

JM: That’s often been a subtle feature my work and something I’ve never worried about. One of my favourite photographers of all time, Lee Friedlander, produced a whole book of self-portraits of himself out on the street, often appearing as just a subtle shadow or reflection within a broader scene.

RR: What’s the urban landscape offer & how frustrating can it be at times in regards to finding subjects or situations to shoot candidly?

JM: I love the uncertainty and endless possibilities of it. If I knew what I was going to be shooting every day, I’d have quickly bored of it years ago. There are days and weeks where I see nothing and accepting that is part of my creative process…

RR: You embrace the ‘not knowing’, the surprise …

JM: That’s right, the ‘not knowing’ part for me is the challenge — it’s a way of thinking and seeing and can be applied wherever I may be around the world. I have a few central stylistic themes that have always run through my work but the general idea, that I can leave the house one morning and come home with a photo that will become part of a bigger series, continues to drive and excite me.

RR: At what age did you first pick up a camera and what was the initial allure and was it immediate?

JM: I first started taking photos as an eight-year-old boy. My uncle gave me a book called ‘Subway Art’ which documented the NYC subway graffiti scene. My parents have always been very supportive of my interest in the arts. They’ve owned a small women’s fashion shop in Melbourne called Blonde Venus for 40 years. My mum designs the clothes and dad runs the business and sells them. So, in the mid 1980’s when I was eight and had been given the graffiti book, something was triggered inside me. I began taking photos [with my mum’s camera] of the first wave of graffiti walls that began appearing around Melbourne. I’d go out with my mum on weekends and school holidays searching for walls, and I’d jump out of the car and shoot photos. I’ve been looking to publish this series as a book and it will hopefully be my next book project. 35 years later, I’m still as inspired as ever.

RR: What do you feel distinguishes your work from others categorised as ’street photographers’?

JM: That’s a tricky question. I feel my work has evolved over the last 20 years from initially being inspired by the classics, and shooting B&W, to finding more of my own voice. In my more recent work, I find myself looking for a combination of strong colour, a sense of design and a human or graphic element.

RR: That moniker, ’street photographer’, has that arguably been cannibalised and overused the past decade?

JM: It’s certainly become a big thing in the last 15 years. When I started off in 1997, the idea of just walking around with a camera and looking for random photos on the street didn’t have any particular name to it and there certainly weren’t many people practising it. Seeing another photographer out on the street was a rare thing. Nowadays, it’s quite the opposite. In 2000, the first online street photographers collective was formed and I was lucky enough to join them in 2001. In the last 10 years, the street photography genre has grown in so many ways. I’ve lost count of the number of online collectives and festivals are happening around the world now brands and camera companies have embraced the genre and term ‘Street Photography’, as have book publishers. It’s always been such an accessible form of photography — you don’t need a tripod, model, studio, fancy lights — so I’ve seen its growth and popularity really sky rocket in the time I’ve been a part of the scene.

RR: 2020 and the various COVID-enforced lock-downs must have been arduous for a photographer who roams like you do?

JM: Having my commercial work put on hold for that period certainly had its challenges. I tried to stay positive and focused on what I could still do — that meant daily drives to the shops after homeschooling my two children, just to get out there and shoot a bit. However, the time off gave me the opportunity to produce the book and also recommence my street posters, which I had dabbled with back in the mid-2000s.

RR: You sometimes instruct and take ‘classes’ as part of Leica’s Akademie – what are the main tips you impart to those wanting to take a decent picture?

JM: Yes, I’ve been a Leica ambassador for the last six years and regularly run workshops via the Akademie. There are a couple of shooting approaches I try to teach people if they are starting off on the street and it mainly focuses on building confidence. For the more advanced shooters that come along, I really try to help them refine their vision and build their own sense of visual consistency.

Second City is available now, $75; jessemarlow.com

Subscribe to the Newsletter

Recommended for you

A Secondary Eye

Seeking bang for your artwork bucks? A new private gallery in Sydney is here to help investors.

May 24, 2024

Everybody Loves Naomi

Fashion fans adore her. And so do we. Lucky, then, that a new exhibition is paying homage to the undisputed queen of the catwalk.

By Joseph Tenni

June 22, 2024

You may also like.

You may also like.

How Paris’s Dining, Hotel and Art Scene Got Their Groove Back — Just in Time for the Olympics

The French capital’s cultural life was already on the upswing. Mix in a major global sporting event, and it’s now ready to go toe to toe with any city in the world.

Host cities of modern-day Olympic Games have gotten into the competitive spirit by trying to stage the most spellbinding, over-the-top opening ceremony on record. Beijing enlisted 2008 drummers. London featured James Bond escorting Queen Elizabeth II. All Rio needed to wow the crowd was Gisele, who turned the stadium into her personal catwalk, strutting the length of the field solo. But only Paris could make the unprecedented gamble that the city itself is spectacular enough to be the star of the show.

If all goes according to plan when the Summer Olympics alight in Paris this July, the opening ceremony will play out like a Hollywood epic: timed to coincide with the sinking of the sun, an open-air flotilla of boats will ferry the athlete delegations on the Seine, sailing toward the sunset as hundreds of thousands of spectators cheer from either side of the river’s banks and the bridges above, all bathed in the amber afterglow.

Nico Therin

It will mark the first time the ceremony will be held outside a stadium, let alone on a waterway. So too many of the events themselves, instead of being mounted in mostly generic stadiums on the outskirts of the city, will take place in the heart of Paris, reframing the French capital in a way that locals and visitors alike have never experienced—and that’s sure to dial up the promise of pageantry and emotion.

The Eiffel Tower’s latticed silhouette will serve as the backdrop for beach volleyball at Champs de Mars. Place de la Concorde, where more than a thousand people (including Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette) had their heads lopped off during the French Revolution, will be the site of newly admitted Olympic sports such as skateboarding and breakdancing. And though Olympic swimmers have raced in pools since 1908, this year’s athletes are slated to compete in the river itself. (Competitions will also take place in cities across France, from Lyon to Marseille, and Tahiti in French Polynesia will host the surfing event.)

The specs are ambitious and inventive, and in some ways could restore the city’s reputation for audacity. Because while the City of Light may be known as the cradle of fashion, culture and gastronomy, not too long ago it was also regularly accused of slipping into a lazy, even smug, complacency—stuck in its ways, resting on the laurels of its storied past.

In the food world, those doldrums translated into controversial snubs from the influential World’s 50 Best Restaurants list, known for flushing out avant-garde chefs. The French Michelin Guide, once considered the ultimate arbiter of fine dining, suddenly seemed staid and irrelevant. London and Berlin took Europe’s centre stage in art and design. Even President Emmanuel Macron described his fellow countrymen as resistant to change, much to the ire of those fellow countrymen—and countrywomen.

But influential creatives and Parisians say that in the years leading up to the Games, and particularly since the pandemic, something has shifted. “I really think that during the last 10 years, Paris opened itself to more new things, for different trends,” says Hélène Darroze, the acclaimed chef whose six restaurants include Michelin two-star Marsan in Paris and her three-star namesake at The Connaught in London. “Paris is happier than before, more joyful than before.”

There’s a giddy sense of anticipation, says the illustrator Marin Montagut, who has collaborated with Le Bon Marché and the Ritz Paris and owns an eponymous boutique in Saint-Germain-des-Prés where he sells hand-painted glassware and porcelain decor. “It feels like Paris is trying to look very, very pretty for a very important evening. She’s been getting some plastic surgery and is trying to get ready in time,” he says with a chuckle. “There’s just a lot of effervescence in the city.”

Nico Therin

For better or for worse, some of the credit for that renewed vitality belongs to the light-as-soufflé Netflix series Emily in Paris, which quickly became the collective escapist fantasy for viewers around the world who were grounded by the Covid-19 virus. Another part of that newfound energy, though, can be traced to the frenzied building of luxury hotels, restaurants, galleries, museums and boutiques over the past few years, including Montagut’s own Paris-themed shop, which he opened in 2020.

In the past three years alone, 25 new five-star hotels debuted across the city, bringing the total to 101. Noteworthy newcomers include Madame Rêve, Kimpton St. Honoré Paris, Château des Fleurs, Maison Proust, LVMH’s Cheval Blanc Paris, and Chopard’s first boutique hotel here, 1 Place Vendôme. The dual autumn 2023 openings of Le Grand Mazarin and La Fantaisie hotels marked the Paris debut of Swedish designer Martin Brudnizki, whose playfully modern, maximalist and flamboyant aesthetic injected colour and character into Paris’s elite hotel scene.

In parallel with the growth of traditional hotels, new players in the luxury rental market are emerging, joining the likes of Le Collectionist and Belles Demeures. Founded in 2020, Highstay rents out luxury serviced apartments equipped with kitchens and living spaces. The firm’s current portfolio includes 36 apartments in areas such as the Champs-Élysées and Saint-Honoré, and another 48 are under construction—all of which it owns. There is no check-in (guests are sent digital access codes) and all concierge requests, including housekeeping and travel reservations, are made via live chat on a dedicated guest portal. “The goal is that guests get the real Parisian experience and feel like an insider, like a city dweller,” says general director Maxime Lallement.

The idea of making Paris as welcoming as a second home is also what drives the luxury real-estate market for foreign buyers, particularly Americans, says Alexander Kraft, CEO of Sotheby’s International Realty France-Monaco. He sees 2024 as a “transition year” and says that the local market is moving at two different speeds: while demand for properties between roughly $1.5 million and $8.5 million has cooled, high-end properties between about $17 million and $85 million continue to sell fast among buyers from the Middle East. Kraft predicts the market will pick up in 2025 following the US presidential election. “Paris is one of those real-estate markets that is eternally popular,” he says. “Contrary to other international cities, it really has broad appeal.”

Nico Therin

Montreal-born, New York–based interior designer Garrow Kedigian is one of those frequent visitors who decided to take the leap and buy his own pied-à-terre in Paris a few years ago, after a lifetime of travelling back and forth for both work and pleasure.

As a part-time resident, Kedigian says he too has noticed a palpable shift in the city’s vibe, which he attributes to a renewed appreciation for tourists following their absence during the pandemic, as well as an “international flair” that has given the city a fresh spark. “There’s a lot more cultural diversity than there was before,” he says. “In that respect it’s a bit like New York. And I think that now the interface between Paris’s unique flavour and the international populace is a little bit smoother.”

For Montagut, one of the best examples of this synergy can be found in Belleville, in the city’s east end, where independent artists, musicians and other urban creatives rub shoulders in Chinese, African, and Arab restaurants and businesses. “There’s a social and cultural diversity here, and for me this is really important,” Montagut says. “If Paris was just the 6th arrondissement, it would be boring.”

The eastern edge of Paris is also one of the preferred neighbourhoods of Michael Schwartz, the marketing and communications manager for Europe at French jewellery house Boucheron. A recent New York City transplant, he is drawn to the burgeoning number of gastronomic gems far from the madding tourist crowds.

Nico Therin

He points to sister restaurants Caché and Amagat (the names mean “hidden” in French and Catalan, respectively), discreetly located at the end of a cobblestoned cul-de-sac, as favourites. With backgrounds in fashion and advertising, the Italian duo who run them have attracted equally fashionable locals to this hitherto quiet part of town. Caché serves up fresh Mediterranean seafood dishes, while next door, Amagat specialises in Catalan tapas.

Then there’s Soces, a corner seafood bistro on rue de la Villette, where you might find Jean-Benoît Dunckel, who co-wrote the score to Sofia Coppola’s film The Virgin Suicides when he was part of the electronic-music duo Air (Dunckel’s recording studio is in the area), or the French designers behind the Coperni fashion line, Sébastien Meyer and Arnaud Vaillant. “This is a really special restaurant,” says Schwartz. “It’s frequented by really cool creatives, designers and musicians, and it’s kind of a destination restaurant for most people because it’s not central.”

What makes Paris’s dining scene so exciting now, according to Stéphane Bréhier, editor in chief of French restaurant guide Gault& Millau, is a sense of fearlessness among younger chefs who reject the traditional trajectory that begins with a lowly stage in a Michelin-star kitchen. What’s more, visitors are likewise foregoing Michelin establishments in favour of newer, more experimental dining spots. “Over the last few years, there’s been a profusion of young chefs who don’t want to work for other people and are daring to set up their own shop,” Bréhier says. “The gastronomic scene is booming in Paris.”

Nico Therin

These bold, emerging chefs feel less bound not only to their elders but also to French cuisine itself. “It has changed a lot,” says Hélène Darroze, who opened Marsan, her first Parisian restaurant, 25 years ago. “The new generation travelled a lot—in South America, for example, in Asia—before opening a restaurant or being a head chef somewhere. They opened themselves to other cultures. This is why the culinary scene at the moment is very interesting in Paris; because it’s a mix of very famous chefs with Michelin stars but also young chefs who don’t care about Michelin stars—they just want to explore so many fields.”

The ever-growing importance of social media and its insatiable hunger for envy-inducing images is driving another major trend in the dining scene: rooftop spots, including Mun and Girafe in the Golden Triangle, the area bordered by avenues Montaigne and George V and the Champs-Élysées. “A lot of rooftops have opened in Paris, where before they were pretty much nonexistent apart from the Eiffel Tower and the Montparnasse Tower,” says Dimitri Ruiz, head concierge at Hôtel Barrière Fouquet’s Paris on the Champs-Élysées.

Five-star Right Bank hotels SO/ and Cheval Blanc Paris have watering holes that offer sweeping vistas of the Seine. But perhaps the most coveted perch during the opening ceremony will be the Champagne bar at La Tour d’Argent restaurant, which boasts unobstructed views of the Notre-Dame Cathedral and the Seine. (And yes, someone already had the idea to book it for a private event.) Famous for its signature pressed duck as well as for hosting monarchs and heads of state, the historic restaurant recently underwent a major renovation that included the addition of the aerie, which opened late last summer. “It’s only been in the last 10 years or so that Paris has been developing rooftops, and it’s really taking off like wildfire,” says third-generation owner André Terrail.

Paris’s venerated fashion industry has also found ways to innovate, with fresh faces keeping their fellow couturiers on their toes and the shopping options enticing. In 2022, for example, Simon Porte Jacquemus opened his first boutique in the city on avenue Montaigne—home to Gucci, Chanel, and Prada, among other venerable names—and in March, at the age of 34, became France’s youngest fashion designer to be named a Chevalier de l’Ordre des Arts et des Lettres for his contributions to the field. That kind of success has a ripple effect in the creative community.

“Almost every street has the name of an artist or a politician,” says Charaf Tajer, the Parisian-born creative director behind the London-based Casablanca sportswear line. “So the city reminds me always that the people who came before me, who walked those streets, created the future in a way. As much as [Paris] seems stuck in time visually, you can also feel the energy of people creating the present.”

Interior designer David Jimenez, whose 2022 book Parisian by Design compiles his Francophile projects, moved to the city in 2015 and spent his first few years living near the Champs-Élysées, which he says has undergone a noticeable revival. Along with Jacquemus’s arrival, new luxury openings or expansions—including Burberry, Saint Laurent, Bottega Veneta, and Panerai—and city-led greening efforts are bringing Parisians back to the 8th arrondissement, long dismissed as an overcrowded tourist trap where fast-food and fast-fashion chains had colonised the once glamorously luxe avenue. Now, Dior’s captivating Peter Marino–designed museum draws legions of fans, while the city has been busy planting more trees, renovating gardens and repairing damaged sidewalks as part of a long-term embellishment plan. And on the first Sunday of every month, the entire length of the Champs-Élysées becomes a pedestrian-only promenade. “It’s an exciting evolution in a part of the city that seemed sleepy and perhaps lost its way a little bit,” Jimenez says. “Now there’s a thrust forward.”

Nico Therin

The thriving fashion houses are responsible for more than maintaining the city’s unparalleled reputation for chic. To a large degree, they have also helped revive its status as an art capital. The billions generated by LVMH (parent of Louis Vuitton, Dior and Berluti, among others) and Kering (Alexander McQueen, Gucci, Bottega Veneta, et al.) funded the extraordinary contemporary art collections amassed by their founders, Bernard Arnault and François Pinault, respectively. The rivals rewarded their hometown with two museums, Fondation Louis Vuitton and Bourse de Commerce, that have helped make it a leader in contemporary art.

Also lending a hand: Brexit, which persuaded many international galleries to brush up on their French. One of the most talked-about recent additions is the powerhouse Hauser & Wirth, which opened in a 19th-century hôtel particulier near the Champs-Élysées last year. David Zwirner arrived in 2019, Mariane Ibrahim in 2021, and Peter Kilchmann the following year, all joining long-established Parisian galleries including Perrotin and Thaddaeus Ropac. The City of Light even snagged its own coveted annual installment of Art Basel: Paris+, which now runs every October in the Grand Palais.

“Quite frankly, Paris has been putting up some of the most incredible exhibitions in institutions in Europe,” says Serena Cattaneo Adorno, senior director at Gagosian. “And a lot of private collectors have also decided to open spaces in the city, creating a great dynamic between public and private galleries.”

The always-savvy Gagosian, on rue Ponthieu, has hit upon an authentic tie-in with the Games: a summer exhibition featuring Olympic posters created over the years by celebrated artists from Picasso on up to Warhol, Hockney and Tracey Emin. “Once you start digging, you find that a lot of artists have reflected on sports and the engagement of the body,” Cattaneo Adorno says. “It’s just a really pure and beautiful message about how art and sports have dialogues that can be somewhat surprising.”

A few months out from the festivities on the Seine, interior decorator Jimenez sums up the mood of many locals, saying (only half-jokingly), “I think for most Parisians, there’s a sense of curiosity, optimism, excitement—and an exit plan, in that order.”

While polling shows that nearly half of Parisians intend to vacate the city during the games, Jimenez notes that he will be watching the opening ceremony with friends who live in an apartment overlooking the Seine. “I want to be part of the excitement. I want to see as much as I can and be energised by this very special and unique moment,” he says. “It’s a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity, and I am deeply grateful to be able to experience it first-hand as an American living in Paris.”

Additional reporting by Lucy Alexander and Justin Fenner.

You may also like.

By Josh Bozin

24/07/2024

5 Lounge Chairs That Add Chic Seating to Your Space

Daybeds, the most relaxed of seating solutions, offer a surprising amount of utility.

Chaise longue, daybed, recamier, duchesse brisée—elongated furniture designed for relaxing has a roster of fancy names. While the French royal court of Louis XIV brought such pieces to prominence in fashionable European homes, the general idea has been around far longer: The Egyptian pharaohs were big fans, while daybeds from China’s Ming dynasty spurred all those Hollywood Regency fretwork pieces that still populate Palm Beach living rooms. Even Mies van der Rohe, one of design’s modernist icons, got into the lounge game with his Barcelona couch, a study of line and form that holds up today.

But don’t get caught up in who invented them, or what to call them. Instead, consider their versatility: Backless models are ideal in front of large expanses of glass (imagine lazing on one with an ocean view) or at the foot of a bed, while more structured pieces can transform any corner into a cozy reading nook. Daybeds may be inextricably linked to relaxation, but from a design perspective, they put in serious work.

Emmy, Egg Collective

In designing the Emmy chaise, the Egg Collective trio of Stephanie Beamer, Crystal Ellis and Hillary Petrie, who met as students at Washington University in St. Louis, aimed for versatility. Indeed, the tailored chaise looks equally at home in a glass skyscraper as it does in a turn-of-the-century town house. Combining the elegance of a smooth, solid oak or walnut frame with the comfort of bolsters and cushioned upholstery or leather, it works just as well against a wall or at the heart of a room. From around $7,015; Eggcollective.com

Plum, Michael Robbins

Plum, Michael Robbins

Woodworker Michael Robbins is the quintessential artisan from New York State’s Hudson Valley in that both his materials and methods pay homage to the area. In fact, he describes his style as “honest, playful, elegant and reflective of the aesthetic of the Hudson Valley surroundings”. Robbins crafts his furniture by hand but allows the wood he uses to help guide the look of a piece. (The studio offers eight standard finishes.) The Plum daybed, brought to life at Robbins’s workshop, exhibits his signature modern rusticity injected with a hint of whimsy thanks to the simplicity of its geometric forms. Around $4,275; MichaelRobbins.com

Kimani, Reda Amalou Design

French architect and designer Reda Amalou acknowledges the challenge of creating standout seating given the number of iconic 20th-century examples already in existence. Still, he persists—and prevails. The Kimani, a bent slash of a daybed in a limited edition of eight pieces, makes a forceful statement. Its leather cushion features a rolled headrest and rhythmic channel stitching reminiscent of that found on the seats of ’70s cars; visually, these elements anchor the slender silhouette atop a patinated bronze base with a sure-handed single line. The result: a seamless contour for the body. Around $33,530; RedaAmalou

Dune, Workshop/APD

From a firm known for crafting subtle but luxurious architecture and interiors, Workshop/APD’s debut furniture collection is on point. Among its offerings is the leather-wrapped Dune daybed. With classical and Art Deco influences, its cylindrical bolsters are a tactile celebration, and the peek of the curved satin-brass base makes for a sensual surprise. Associate principal Andrew Kline notes that the daybed adeptly bridges two seating areas in a roomy living space or can sit, bench-style, at the foot of a bed. From $13,040; Workshop/ APD

Sherazade, Edra

Designed by Francesco Binfaré, this sculptural, minimalist daybed—inspired by the rugs used by Eastern civilizations—allows for complete relaxation. Strength combined with comfort is the name of the game here. The Sherazade’s structure is made from light but sturdy honeycomb wood, while next-gen Gellyfoam and synthetic wadding aid repose. True to Edra’s amorphous design codes, it can switch configurations depending on the user’s mood or needs; for example, the accompanying extra pillows—one rectangular and one cylinder shaped— interchange to become armrests or backrests. From $32,900; Edra

You may also like.

Watches & Wonders 2024 Showcase: Hermès

We head to Geneva for the Watches & Wonders exhibition; a week-long horological blockbuster featuring the hottest new drops, and no shortage of hype.

With Watches & Wonders 2024 well and truly behind us, we review some of the novelties Hermès presented at this year’s event.

—

HERMÈS

Moving away from the block colours and sporty aesthetic that has defined Hermès watches in recent years, the biggest news from the French luxury goods company at Watches & Wonders came with the unveiling of its newest collection, the Hermès Cut.

It flaunts a round bezel, but the case middle is nearer to a tonneau shape—a relatively simple design that, despite attracting flak from some watch aficionados, works. While marketed as a “women’s watch”, the Cut has universal appeal thanks to its elegant package and proportions. It moves away from the Maison’s penchant for a style-first product; it’s a watch that tells the time, not a fashion accessory with the ability to tell the time.

Hermès gets the proportions just right thanks to a satin-brushed and polished 36 mm case, PVD-treated Arabic numerals, and clean-cut edges that further accentuate its character. One of the key design elements is the positioning of the crown, boldly sitting at half-past one and embellished with a lacquered or engraved “H”, clearly stamping its originality. The watch is powered by a Hermès Manufacture movement H1912, revealed through its sapphire crystal caseback. In addition to its seamlessly integrated and easy-wearing metal bracelet, the Cut also comes with the option for a range of coloured rubber straps. Together with its clever interchangeable system, it’s a cinch to swap out its look.

It will be interesting to see how the Hermès Cut fares in coming months, particularly as it tries to establish its own identity separate from the more aggressive, but widely popular, Ho8 collection. Either way, the company is now a serious part of the dialogue around the concept of time.

—

Read more about this year’s Watches & Wonders exhibition at robbreport.com.au

You may also like.

Living La Vida Lagerfeld

The world remembers him for fashion. But as a new tome reveals, the iconoclastic designer is defined as much by extravagant, often fantastical, homes as he is clothes.

“Lives, like novels, are made up of chapters”, the world-renowned bibliophile, Karl Lagerfeld, once observed.

Were a psychological-style novel ever to be written about Karl Lagerfeld’s life, it would no doubt give less narrative weight to the story of his reinvigoration of staid fashion houses like Chloe, Fendi and Chanel than to the underpinning leitmotif of the designer’s constant reinvention of himself.

In a lifetime spanning two centuries, Lagerfeld made and dropped an ever-changing parade of close friends, muses, collaborators and ambiguous lovers, as easily as he changed his clothes, his furniture… even his body. Each chapter of this book would be set against the backdrop of one of his series of apartments, houses and villas, whose often wildly divergent but always ultra-luxurious décor reflected the ever-evolving personas of this compulsively public but ultimately enigmatic man.

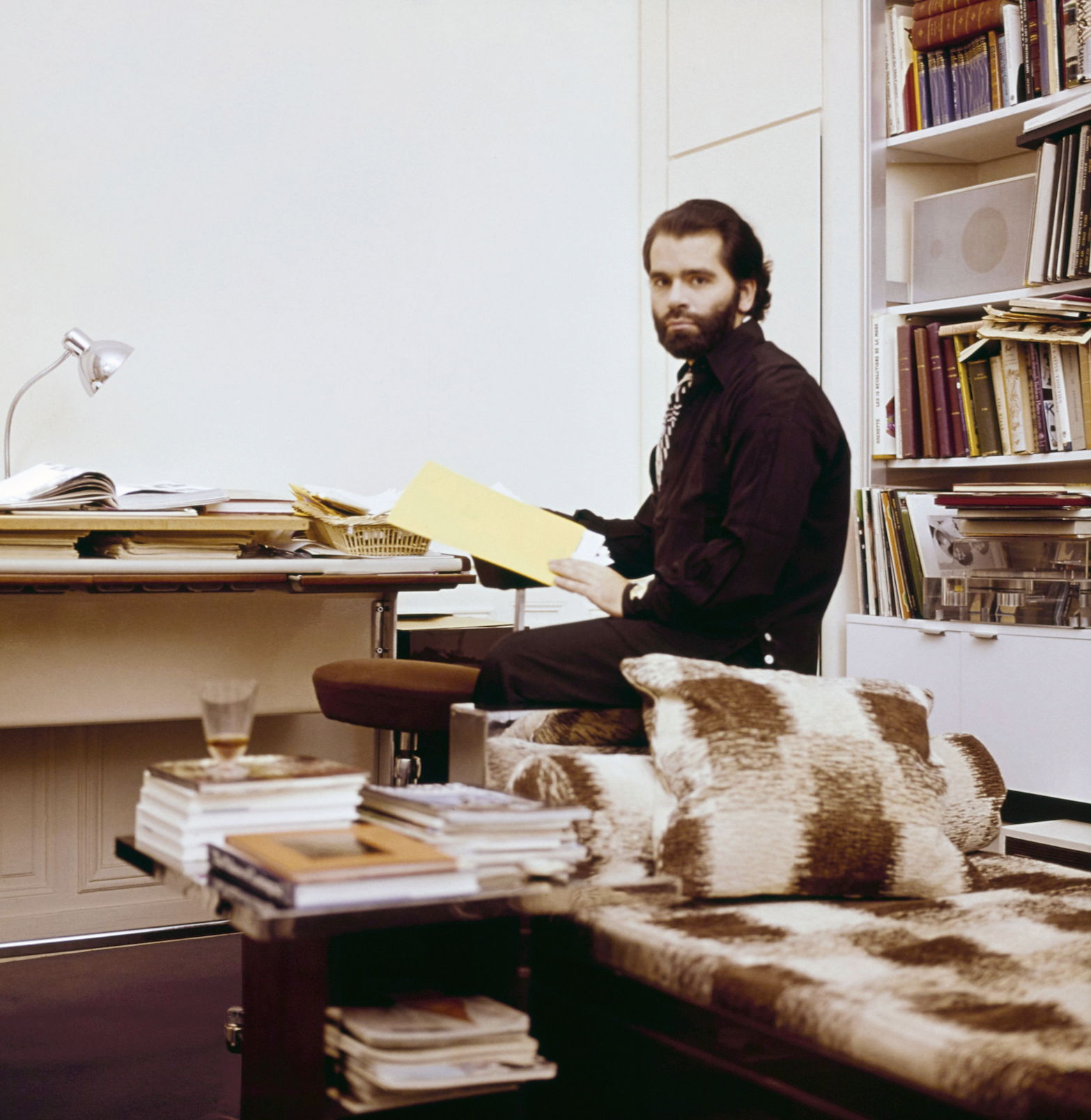

With the publication of Karl Lagerfeld: A Life in Houses these wildly disparate but always exquisite interiors are presented for the first time together as a chronological body of work. The book indeed serves as a kind of visual novel, documenting the domestic dreamscapes in which the iconic designer played out his many lives, while also making a strong case that Lagerfeld’s impact on contemporary interior design is just as important, if not more so, than his influence on fashion.

In fact, when the first Lagerfeld interior was featured in a 1968 spread for L’OEil magazine, the editorial describes him merely as a “stylist”. The photographs of the apartment in an 18th-century mansion on rue de Université, show walls lined with plum-coloured rice paper, or lacquered deepest chocolate brown in sharp contrast to crisp, white low ceilings that accentuated the horizontality that was fashionable among the extremely fashionable at the time. Yet amid this setting of aggressively au courant modernism, the anachronistic pops of Art Nouveau and Art Deco objects foreshadow the young Karl’s innate gift for creating strikingly original environments whose harmony is achieved through the deft interplay of contrasting styles and contexts.

Lagerfeld learned early on that presenting himself in a succession of gem-like domestic settings was good for crafting his image. But Lagerfeld’s houses not only provided him with publicity, they also gave him an excuse to indulge in his greatest passion. Shopping!

By 1973, Lagerfeld was living in a new apartment at Place Saint–Sulpice where his acquisition of important Art Deco treasures continued unabated. Now a bearded and muscular disco dandy, he could most often be found in the louche company of the models, starlets and assorted hedonistic beauties that gathered around the flamboyant fashion illustrator Antonio Lopez. Lagerfeld was also in the throes of a hopeless love affair with Jacques de Bascher whose favours he reluctantly shared with his nemesis Yves Saint Laurent.

He painted the rooms milky white and lined them with specially commissioned carpets—the tawny patterned striations of which invoked musky wild animal pelts. These lent a stark relief to the sleek, machine-age chrome lines of his Deco furnishings. To contemporary eyes it remains a strikingly original arrangement that subtly conveys the tensions at play in Lagerfeld’s own life: the cocaine fuelled orgies of his lover and friends, hosted in the pristine home of a man who claimed that “a bed is for one person”.

In 1975, a painful falling out with his beloved Jacques, who was descending into the abyss of addiction, saw almost his entire collection of peerless Art Deco furniture, paintings and objects put under the auctioneer’s hammer. This was the first of many auction sales, as he habitually shed the contents of his houses along with whatever incarnation of himself had lived there. Lagerfeld was dispassionate about parting with these precious goods. “It’s collecting that’s fun, not owning,” he said. And the reality for a collector on such a Renaissance scale, is that to continue buying, Lagerfeld had to sell.

Of all his residences, it was the 1977 purchase of Hôtel Pozzo di Borgo, a grand and beautifully preserved 18th-century house, that would finally allow him to fulfill his childhood fantasies of life in the court of Madame de Pompadour. And it was in this aura of Rococó splendour that the fashion designer began to affect, along with his tailored three-piece suits, a courtier’s ponytailed and powdered coif and a coquettish antique fan: marking the beginning of his transformation into a living, breathing global brand that even those with little interest in fashion would immediately recognise.

Lagerfeld’s increasing fame and financial success allowed him to indulge in an unprecedented spending frenzy, competing with deep-pocketed institutions like the Louvre to acquire the finest, most pedigreed pearls of the era—voluptuously carved and gilded bergères; ormolu chests; and fleshy, pastel-tinged Fragonard idylls—to adorn his urban palace. His one-time friend André Leon Talley described him in a contemporary article as suffering from “Versailles complex”.

However, in mid-1981, and in response to the election of left-wing president, François Mitterrand, Lagerfeld, with the assistance of his close friend Princess Caroline, became a resident of the tax haven of Monaco. He purchased two apartments on the 21st floor of Le Roccabella, a luxury residential block designed by Gio Ponti. One, in which he kept Jacques de Bascher, with whom he was now reconciled, was decorated in the strict, monochromatic Viennese Secessionist style that had long underpinned his aesthetic vocabulary; the other space, though, was something else entirely, cementing his notoriety as an iconoclastic tastemaker.

Lagerfeld had recently discovered the radically quirky designs of the Memphis Group led by Ettore Sottsass, and bought the collective’s entire first collection and had it shipped to Monaco. In a space with no right angles, these chaotically colourful, geometrically askew pieces—centred on Masanori Umeda’s famous boxing ring—gave visitors the disorientating sensation of having entered a corporeal comic strip. By 1991, the novelty of this jarring postmodern playhouse had inevitably worn thin and once again he sent it all to auction, later telling a journalist that “after a few years it was like living in an old Courrèges. Ha!”

In 1989, de Bascher died of an AIDS-related illness, and while Lagerfeld’s career continued to flourish, emotionally the famously stoic designer was struggling. In 2000, a somewhat corpulent Lagerfeld officially ended his “let them eat cake” years at the Hôtel Pozzo di Borgo, selling its sumptuous antique fittings in a massive headline auction that stretched over three days. As always there were other houses, but now with his longtime companion dead, and his celebrity metastasising making him a target for the paparazzi, he began to look less for exhibition spaces and more for private sanctuaries where he could pursue his endless, often lonely, work.

His next significant house was Villa Jako, named for his lost companion and built in the 1920s in a nouveau riche area of Hamburg close to where he grew up. Lagerfeld shot the advertising campaign for Lagerfeld Jako there—a fragrance created in memorial to de Bascher. The house featured a collection of mainly Scandinavian antiques, marking the aesthetic cusp between Art Nouveau and Art Deco. One of its rooms Lagerfeld decorated based on his remembrances of his childhood nursery. Here, he locked himself away to work—tellingly—on a series of illustrations for the fairy tale, The Emperor’s New Clothes. Villa Jako was a house of deep nostalgia and mourning.

But there were more acts—and more houses—to come in Lagerfeld’s life yet. In November 2000, upon seeing the attenuated tailoring of Hedi Slimane, then head of menswear at Christian Dior, the 135 kg Lagerfeld embarked on a strict dietary regime. Over the next 13 months, he melted into a shadow of his former self. It is this incarnation of Lagerfeld—high white starched collars; Slimane’s skintight suits, and fingerless leather gloves revealing hands bedecked with heavy silver rings—that is immediately recognisable some five years after his death.

The 200-year-old apartment in Quái Voltaire, Paris, was purchased in 2006, and after years of slumber Lagerfeld—a newly awakened Hip Van Winkle—was ready to remake it into his last modernist masterpiece. He designed a unique daylight simulation system that meant the monochromatic space was completely without shadows—and without memory. The walls were frosted and smoked glass, the floors concrete and silicone; and any hint of texture was banned with only shiny, sleek pieces by Marc Newson, Martin Szekely and the Bouroullec Brothers permitted. Few guests were allowed into this monastic environment where Lagerfeld worked, drank endless cans of Diet Coke and communed with Choupette, his beloved Birman cat, and parts of his collection of 300,000 books—one of the largest private collections in the world.

Lagerfeld died in 2019, and the process of dispersing his worldly goods is still ongoing. The Quái Voltaire apartment was sold this year for US$10.8 million (around $16.3 million). Now only the rue de Saint-Peres property remains within the Lagerfeld trust. Purchased after Quái Voltaire to further accommodate more of his books—35,000 were displayed in his studio alone, always stacked horizontally so he could read the titles without straining his neck—and as a place for food preparation as he loathed his primary living space having any trace of cooking smells. Today, the rue de Saint-Peres residence is open to the public as an arts performance space and most fittingly, a library.

You may also like.

Watch This Space: Mike Nouveau

Meet the game-changing horological influencers blazing a trail across social media—and doing things their own way.

In the thriving world of luxury watches, few people own a space that offers unfiltered digital amplification. And that’s precisely what makes the likes of Brynn Wallner, Teddy Baldassarre, Mike Nouveau and Justin Hast so compelling.

These thought-provoking digital crusaders are now paving the way for the story of watches to be told, and shown, in a new light. Speaking to thousands of followers on the daily—mainly via TikTok, Instagram and YouTube—these progressive commentators represent the new guard of watch pundits. And they’re swaying the opinions, and dollars, of the up-and-coming generations who now represent the target consumer of this booming sector.

—

MIKE NOUVEAU

Can we please see what’s on the wrist? That’s the question that catapulted Mike Nouveau into watch stardom, thanks to his penchant for highlighting incredibly rare timepieces across his TikTok account of more than 400,000 followers. When viewing Nouveau’s attention-grabbing video clips—usually shot in a New York City neighbourhood—it’s not uncommon to find him wrist-rolling some of the world’s rarest timepieces, like the million-dollar Cartier Cheich (a clip he posted in May).

But how did someone without any previous watch experience come to amass such a cult following, and in the process gain access to some of the world’s most coveted timepieces? Nouveau admits had been a collector for many years, but moved didn’t move into horology full-time until 2020, when he swapped his DJing career for one as a vintage watch specialist.

“I probably researched for a year before I even bought my first watch,” says Nouveau, alluding to his Rolex GMT Master “Pepsi” ref. 1675 from 1967, a lionised timepiece in the vintage cosmos. “I would see deals arise that I knew were very good, but they weren’t necessarily watches that I wanted to buy myself. I eventually started buying and selling, flipping just for fun because I knew how to spot a good deal.”

Nouveau claims that before launching his TikTok account in the wake of Covid-19, no one in the watch community knew he existed. “There really wasn’t much watch content, if any, on TikTok before I started posting, especially talking about vintage watches. There’s still not that many voices for vintage watches, period,” says Nouveau. “It just so happens that my audience probably skews younger, and I’d say there are just as many young people interested in vintage watches as there are in modern watches.”

View this post on Instagram

Nouveau recently posted a video to his TikTok account revealing that the average price of a watch purchased by Gen Z is now almost US$11,000 (around $16,500), with 41 percent of them coming into possession of a luxury watch in the past 12 months.

“Do as much independent research as you can [when buying],” he advises. “The more you do, the more informed you are and the less likely you are to make a mistake. And don’t bring modern watch expectations to the vintage world because it’s very different. People say, ‘buy the dealer’, but I don’t do that. I trust myself and myself only.”

—

Read more about the influencers shaking up horology here with Justin Hast, Brynn Wallner and Teddy Baldassare.