How Malta Became a Modern Traveller’s Luxury Paradise Again

Just south of Italy, the archipelago that rose to wealth and power during the Crusades is modernizing its offerings for visitors and locals alike.

They call them Aldo’s fish. The brightly colored, distinctly midcentury patterns on the plates at Villa Bologna Pottery in Malta were designed by Aldo Cremona, who worked there for more than 70 years. Born deaf to a poor family, he had limited schooling and never learned to speak, communicating instead through his vibrant artwork. The facility’s signature scroll design was his handiwork, too, as were a series of water jugs, jauntily daubed with splotches of paint to resemble women. “They were supposed to be saluting admirals, but Aldo didn’t like painting men, so he made them ladies instead,” says the pottery’s owner, Sophie Edwards. Cremona died last year, but there’s still a shelf full of those jugs in the workshop acting as templates for the designs. A small sticker indicates each of their names: Violetta with her bedroom eyes, for instance, or Delft-blue Flora.

COURTESY OF VILLA BOLOGNA

The workshop itself is almost a century old, founded in 1924 as a philanthropic effort to help employ local women, but it has been reenergized in the three years since Edwards and her husband, Rowley, took over. “Everyone in Malta knows the pottery—the pineapple lamps are popular wedding gifts,” she explains. Now, though, the couple hope to build a bigger audience; last year, they opened their first foreign store, in London’s tony Holland Park, and launched e-commerce for America this spring. Every piece will continue to be handmade.

It’s an unexpected story to those who are at all familiar with Malta. Mention the country and most will think of the military might wielded by the bygone Knights of Malta, and perhaps money, but not making things. Today, though, thanks to an influx of wealthy and design-focused new citizens, the tiny, rocky nation is starting to rebrand itself as a source of, and destination for, serious luxury.

Malta, at just 122 square miles, is composed of three islands: the namesake and largest, plus smaller, rural Gozo, and Comino, a shard wedged between the two. The trio sit squat in the center of the Mediterranean and benefit from naturally deep harbors; such geography and geology made it a squabbled-over strategic possession for centuries, most recently held by the British. (The late Queen Elizabeth lived here as a young wife, and her one-time home will soon open as a museum.)

COURTESY OF VILLA BOLOGNA

Malta’s contemporary reputation has focused less on force than on finances, as the country has aimed to act as a Mediterranean answer to the Cayman Islands. Its favorable taxation regime burnished its appeal to wealthy Europeans, who can take up residency here and pay minimal taxes. A citizenship-by-investment program, in which a passport is yours for a million or so euros, has increased the numbers of high-net-worth residents from other regions, too. The policy has not been without controversy since the government introduced it in 2013 under former premier Joseph Muscat—and that administration remains embroiled in the scandal around the murder of investigative journalist Daphne Caruana Galizia six years ago, which precipitated Muscat’s resignation in early 2020 and continues to swirl.

There has been tourism in Malta over the years, but it’s been mostly mass-market. Keen to rebuild after World War II, when the country underwent brutal bombardment by the Axis powers, the Maltese constructed cheap hotels that filled up with sun-seeking Britons and Germans, who provided much-needed economic stimulus in the 1960s and ’70s. But such package holidays are falling from favor, and locals are determined to lure a different caliber of client. “We can’t sustain huge amounts of people like that anymore,” says Maltese interior designer Francis Sultana, who’s based in London and is a cultural ambassador for his homeland, where he has a spectacular house. “Malta has to reinvent itself as a place to live that’s full of arts and culture and with a wonderful sea around it.”

SUPPLIED

To that end, Malta is working to reposition itself via travel specialists, such as the luxury operator Red Savannah, which will introduce the country as a recommended destination this fall. Its interest reflects the rising profile for Malta among elite travelers, which is the hard-won product of the government’s concerted efforts to transform its audience, whether by underwriting new cultural assets, tendering abandoned buildings for renovation, or continuing to expand the citizenship-by-investment scheme. When the first such program filled its quota of 1,800 passports, the government simply launched a second one, slightly tweaked. The firm Latitude Residency and Citizenship helps interested would-be Maltese citizens navigate the red tape.

Those new, wealthy tourists and part-time residents are a crucial customer base for Sophie and Rowley Edwards. Sophie grew up partly on the island and had always mulled a return. They were married at Bologna, the country house on whose estate the pottery sits. When she was pregnant with her first child, the now 4-year-old Rocco, the couple visited and found the ceramics workshop in a precarious state, operating with just three staff, including Aldo. “You’d rummage around in the basement and find old molds and bits of pottery,” she recalls. They set about relaunching the company, retaining its retro aesthetic but sharpening its approach to business. They’re now working with interior designers and private clients on custom commissions, all while building a restaurant in the stable block next door to the workshop, an all-day upscale Italian-accented café with its own garden.

Villa Bologna is in the village of Attard, a smallish settlement in the center of the island, but much of the new energy is focused on the country’s capital, postcard-pretty Valletta. Sitting on a rocky outcrop next to the deepest harbor on the northern coast, it was built as a single project in the 1570s, which conferred a pleasing uniformity to its architecture. The aesthetic is the same Ottoman-influenced style seen throughout Venice. Valletta was cannily master-planned in a grid layout, allowing sea breezes to pass through downtown as natural air-conditioning; even today, the shadier streets remain surprisingly cool in midsummer.

COURTESY OF VILLA BOLOGNA

The old structures here are being artfully redeployed. Take Renzo Piano’s 2015 parliament building, a rippled cube rendered in the same honeyed limestone used to erect its 16th-century neighbors. His initial plan to demolish the ruined former opera house next door proved controversial, so he instead repurposed the bomb-scarred site as an outdoor theater that serves as both a memorial and an amenity. Then there’s the one-time abattoir that reopened two years ago as the Valletta Design Cluster, a WeWork-meets-workshop complex aimed at creative startups whose primary-color-painted doors and windows have a whiff of De Stijl. Local architect David Felice and his firm, AP Valletta, are working on a major new home for the various artworks and tapestries from the city’s cathedral: a glass box grafted onto a series of old houses, earmarked for completion in 2024. And just outside the city walls is arguably the most ambitious creative project in the country: the Malta International Contemporary Art Space, or MICAS, which is set to open its 16,000 square feet of galleries next year.

It’s already a thrilling site to walk around. The iron-beamed skeleton for MICAS’s huge glass-walled rooms sits bolted to the remnants of the Old Ospizio, a 17th-century fortress that stored gunpowder safely away from Valletta proper. The museum’s modernist design, penned by the Florentine architecture firm IPO Studio, forms a stark contrast to those yellowish, weathered walls. Excavations unearthed ancient ruins—the Romans also saw the strategic value of these islands—and so forced the architects to rejigger their vision; another room now incorporates the big bricks into one of its walls.

On a sunny but brisk March day, the redoubtable chair of MICAS, Phyllis Muscat, picks her way through the site with curator and board member Georgina Portelli, proudly pointing to the rooftop sculpture garden, which will be home to temporary commissions and permanent pieces by the likes of Michele Oka Doner and Cristina Iglesias. They hope that MICAS will act as Malta’s answer to London’s Serpentine Galleries, a small but noteworthy space ideal for artistic takeovers, or the seaside Istanbul Modern. It’s already attracting attention: Sculptor Conrad Shawcross has committed to a site-specific installation this October, before the venue is even complete.

Similarly, Sultana, the interior designer, stresses that Malta’s move upscale is actually a return to its roots. Think back to the Knights of Malta, he suggests, the Christian order that combined chivalry, conquest, and care for the needy. Its aristocratic and international members, who helped take Jerusalem during the Crusades and ruled over parts of Greece, Italy, and, briefly, the Caribbean, in addition to Malta, left the island flush with their fortunes. “The Knights were very, very into luxury, so much gold leaf and great paintings,” Sultana says. “So people are not afraid of maximalism here.” He refers to the local aesthetic as “baroque and roll”—as much the Clash as Caravaggio. (Indeed, that serial rebel took refuge here in 1607, fleeing murder charges in Rome, and his largest work sits in the oratory of St. John’s Co-Cathedral.)

“I think of Malta as Marrakech in the Med,” says John Cooney, comparing these islands to the city where Yves Saint Laurent and his entourage formed a chic outpost of creative expats. Cooney is a Swiss Italian entrepreneur who moved to the island with his husband, Kevin Schwasinger, three years ago. Among other ventures, Cooney’s company Forbidden City designed and operated boutiques in Aman’s hotels for several years. He and Schwasinger now live in a converted palazzo originally built for one of the Knights of Malta but are developing a new five-bedroom hotel in a 17th-century complex in what is known as the Three Cities, a trio of towns that share Valletta’s harbor.

The hotel, called Cité Privée Maison Malte, is the first of an intended chain and will open in 18 months’ time alongside 20 residences located on nearby streets, also in old buildings that the couple are painstakingly restoring. Buyers can use the services of the hotel, and they can also deed the properties into the hotel’s rental pool for guests to book. Cooney says the appeal of developing beyond Valletta’s walls is that this part of the island hasn’t yet seen intense, mass tourism, despite being just a short boat ride away—you can take one of the luzzu, or Maltese gondolas, and glide across the harbor in less than 10 minutes. “This part is like living in an old Maltese village, before there were cars—for me that’s what is really enchanting,” he says. “You might have an old lady down the street screaming at the top of her lungs at her daughter, but other than that, there’s no noise.”

COURTESY OF INIALA HOTEL

Most exciting, though, is the raft of new hotels that are set to open, such as Casa Bonavita, a project by Sophie Edwards’s parents, Christopher and Suzanne Sharp, in a 1760 Baroque mansion they acquired about 12 years ago. The couple are the founders of interiors firm the Rug Company, and Suzanne is Maltese. “We’ve always had the problem that people say to us, ‘Where should I stay in Malta?’ And it’s really difficult, so we started thinking about the house we bought—it’s so large, it was a bit of a folly,” Christopher says of the site, which they’ve since painstakingly repurposed into a 17-room hotel set to bow next spring.

The government is supporting such efforts. It has put a grand former office in central Valletta on the market, expressly for conversion into a high-end hotel; the winning bid will be announced this summer. One of those chasing the deal is British businessman Mark Weingard, who moved to Malta from Spain a decade ago for the financial upsides but quickly embraced the island and its culture. He opened the first truly upscale hotel here, Iniala, which straddles several historic townhomes overlooking that harbor. “When you walk around Valletta, you can get confused,” Weingard says. “It’s this fusion of East and West, a mix of Jerusalem and Venice.” Another mark of his confidence in the destination’s uptick: He has just installed L’Enclume’s three-Michelin-starred chef, Simon Rogan, at the Michelin-starred Ion Harbour restaurant, only Rogan’s second site outside England.

But the biggest project is far from Valletta—indeed, it’s on another island entirely: Comino. Barely 1.4 square miles in size, Comino is mostly a protected habitat now, having once been farmland. Just one resident remains, a man in his 70s who lives self-sufficiently on a small plot. There is modern construction on Comino, though, and it’s yet another legacy of that rush to mass tourism in the wake of World War II: two connected sites, on the island’s northern coast, one a hotel complex and the other a series of hotel-operated villas. They’d slumped from their hey-day, booked mostly to package vacationers, and were shuttered four years ago. Malta’s government hoped to hand the sites over to a new developer who would reimagine them entirely for luxury tourism—and that entity was Malta-based Hili Ventures.

Now surrounded by metal fencing, the abandoned buildings have an eerie quality, shabby but solidly constructed with little consideration for the surrounding countryside. The landscape is typical of Malta: low-lying brushland, free of trees, with clusters of shrubs huddled together against the winds. Hili hopes that a recently announced deal with luxury hotelier Six Senses to operate the property will single-handedly draw luxury travelers from around the world to Malta. Only time will tell.”

The Lowdown

GETTING THERE No airlines offer long-haul flights to Valletta, so most North American visitors arrive via a European hub. For charters within Europe, the Maltese private-jet facility is located at the main airport but has its own stand-alone terminal; try Hans Jet for reasonable options. La Valette Club can handle VIP customs and arrival.

GETTING AROUND The archipelago’s roads can be chaotic. It’s smartest to hire a driver to scoot around the islands without white knuckles; Dacoby has the best chauffeurs.

ACCOMMODATIONS The top choice is Valletta’s Iniala Harbour House, with 23 rooms and suites. There are five penthouse-suite-style options—the best, dubbed the Lucija, boasts a private plunge pool. The four-bedroom Hideaway, an annexed property a few doors down from the main hotel, is available for buyouts, too. From about $382 per night.

RESTAURANTS In Valletta, try the Harbour Club for sundowners. Gracy’s, owned and operated by British businessman Greg Nasmyth and his wife, Samantha Rowe-Beddoe, is a members’ club whose brasserie is open to the public: Come on a Sunday for a buzzy afternoon scene or book the plush private karaoke room downstairs. Noni is one of the city’s six restaurants with Michelin stars, run by local chef Jonathan Brincat and his sister and maître d’, Ritienne. The food is playful and unstuffy: Order the superb, deconstructed prawn cocktail.

Outside the city, try Carmen’s, a waterfront bar and restaurant on Għar Lapsi on the south coast—casual but disarmingly delicious, especially on a warm spring day. Il Corsaro, in the historic town of Żurrieq, is owned and run by an old Italian; think freshly made pasta, menus on chalkboards, and a room full of hungry locals.

ACTIVITIES Malta doesn’t have many appealing sandy beaches; instead, expect craggy edges at the waters. Head down to the southern coast for the quietest perches: The swimming holes at Wied iz-Zurrieq are reachable from the rocks, as is the Blue Grotto arch there; the sea off Ghar Lapsi is easily swimmable, too. The walks in and around Dingli Cliffs are spectacular in the late afternoon. For diving, the oldest local club is Atlam SAC; standout sites include the Bristol Beaufighter World War II wreck at 124 feet or the SS Polynesian, a French liner sunk during World War I that lies at 223 feet.

OPERATORS Fischer Travel and Red Savannah, both Robb Report Travel Masters, have expertise in the islands. Note that weather is mostly pleasant year-round, but try to avoid January and February, which can be rainy and cold; December is often surprisingly balmy, while midsummer will be brutally hot.

Subscribe to the Newsletter

Recommended for you

From Outback to Ocean: A Rare Journey Across Queensland’s Wild Edge

Experience the best of Queensland with Morris Escapes’ signature journey, spanning Mt Mulligan Lodge, Morris Nautical yacht adventures and a private island retreat on Pelorus Island.

By Brad Nash

January 8, 2026

This Research Expedition Superyacht Charter Lets You Swim With Humpback Whales

EYOS Expeditions is planning a set of experiences that blend science and fun.

By Nicole Hoey

January 7, 2026

You may also like.

You may also like.

Mauve on Up

Brisbane boutique stay Miss Midgley’s offers a viscerally human experience—especially if you dig pink.

On a sun-bleached corner of Brisbane’s New Farm, where the scent of frangipani mingles with the clink of coffee cups, stands a building that has lived more lives than most people. Once a premier’s residence, an orphanage, a hospital and a private school, the 160-year-old stone structure now finds itself reborn as Miss Midgley’s—a boutique stay that teaches a masterclass in how to make heritage feel modern.

Designed and run by architect-mother-daughter duo Lisa and Isabella White, Miss Midgley’s captures the cultural confidence of a city in bloom. Nowhere is that new confidence more visible than along James Street—the leafy, slow-burn heart of the city’s fashion and dining scene—where Miss Midgley’s sits quietly at the edge, its shell-pink façade glowing in the subtropical light.

Built of Brisbane’s rare volcanic tuff, the building’s soft mauves and pinks are more than aesthetic; they are its identity. Locals still remember its 1950s incarnation as the Pink Flats, and the Whites have honoured that legacy with a contemporary blush-toned exterior, chosen to harmonise with the stone’s peachy undertones. Inside, those hues continue in dusty terracottas, russets and the faint shimmer of brass tapware. “Design can’t afford to be for the sake of fashion,” Isabella White has said. “It has to respond to what’s in front of you.”

That sentiment is tangible in every corner. Five apartments, each with their own idiosyncratic floor plan, occupy the building. Ceilings bloom with heritage plasterwork, 19th-century wallpaper fragments have been preserved in the kitchens, and tiny hand-painted notes left by the architects point out original quirks: a misaligned beam here, a hidden archway there. It’s a kind of adult treasure hunt for design lovers, where discovery feels personal and unforced.

Even the picket fence, a heritage requirement, has been reimagined in corten steel—a sly nod to regulation turned into sculpture. It’s this blend of reverence and rebellion that gives Miss Midgley’s its edge: heritage without starch, nostalgia without sentimentality.

True to Brisbane’s easy elegance, luxury here is measured not in marble or minibar but in proportion, privacy, and personality. Each apartment—from the Drawing Room and the Assembly Hall to the Principal’s Office—is a self-contained sanctuary with its own kitchen, large bathroom and outdoor space. The ground-floor units open onto leafy courtyards and welcome small dogs; upstairs, the larger suites spill onto verandahs shaded by jacarandas.

At the heart of the property lies a solar-heated pool hemmed with tropical greenery and fringed umbrellas—more mid-century Palm Springs than colonial Brisbane. Around it, guests share a petite laundry, a communal library and that rarest of urban luxuries: a car park per apartment. The atmosphere is quietly collegiate—a handful of travellers who might nod to each other on the stairs but otherwise inhabit their own creative bubbles.

The hotel’s namesake, Annie Midgley, lends the project both its name and its spirit. An ambidextrous artist and teacher, she famously instructed two students at once, writing with both hands simultaneously—a fitting metaphor for the dual vision the Whites bring to the building: one hand rooted in history, the other sketching toward the future. “Not famous, yet known,” goes the property’s understated tagline—and indeed, Miss Midgley’s has quietly become that most desirable of addresses: the one whispered about by people who know.

Sustainability isn’t an accessory here; it’s structural. The adaptive reuse of the heritage building is its boldest environmental act. Solar panels power the property; an electric heat pump warms the pool; recycled decking and tiles frame the courtyard. The metre-thick tuff walls regulate temperature naturally, and the amenities follow suit—refillable bath products, biodegradable pods, Seljak blankets spun from textile off-cuts, and compendiums wrapped in Australian-made kangaroo leather. It’s slow luxury in the truest sense.

In a world of carbon-copy hotels, Miss Midgley’s feels deeply human—a place where history isn’t curated behind glass but lives in the warmth of stone and the flicker of afternoon light. The lesson it offers is simple and resonant: that the most elegant modernity often comes not from reinvention, but from listening to what’s already there.

You may also like.

My Brisbane…Monique Kawecki

The Queensland capital is carving its own distinctive take on Australian culture. Here, a clued-up local aesthete takes us around town.

It’s almost a given that all globally minded creatives will, at some juncture in their careers, choose a path that leads directly to one of the planet’s vital cultural hubs—metropolises with the cosmopolitan thrum of New York, the lofty elegance of Paris, the futuristic edge of Tokyo.

True to form, Monique Kawecki’s work odyssey transported her to the buzz of London for over a decade, but the editor and creative consultant now admits to “finding a balance” in Brisbane, using the Queensland capital as a base for generating international content. Together with her husband, industrial designer Alexander Lotersztain, she’s proud to call the fast-blooming city her home.

Driven by curiosity, Monique joins the dots between creative communities and helps bring visionary projects to life through her studio Champ Creative, a space she runs with her twin sister in Tokyo. Her work as co-founder and editorial director of Ala Champ Magazine, a print-turned-digital-media platform rooted in design, architecture and creative culture, allies thinkers and makers who are shaping the future.

EAT

Central

Step underground and you’ll find more than just a Hong Kong-inspired eatery. This vibrant enclave in the CBD is the vision of chef Benny Lam and young restaurateur David Flynn, combining an avant-garde space—designed by up-and-coming J.AR Office—with inventive Asian-fusion plates and a curated Chinese and Australian wine list. Every detail, from the menu to the disco-era soundscape, combines for a memorable experience.

Gerards

A restaurant that has long held its place among Brisbane’s primo venues, and its makeover by J.AR Office has confirmed it is a mainstay in the city. Rich, rammed-earth textures and sleek steel set the stage for the Levantine-inflected fare, where Queensland produce meets Middle Eastern tradition—all served on textured Sally Kerkin tableware that casts the eclectic dishes in an even more visually pleasing light.

DRINK

+81 Aizome Bar

Inspired by the hidden cocktail bars in Tokyo’s Ginza district, an intimate, indigo-hued 10-seater designed by Alexander Lotersztain. The dimly lit space presents drinks served over hand-cut Japanese ice and expertly crafted “neo cocktails” courtesy of mixologist Tony Huang. Champ Creative curated and sourced the artisan-made tableware and glassware from Japan, making sure the experience is as authentic as possible.

Bar Miette

Overlooking the Brisbane River, Australian chef Andrew McConnell has enlisted executive chef Jason Barratt to direct two of his standout dining ventures—this venue and Supernormal—on the waterfront at 443 Queen Street. Both offer stellar dining—the milk bun with mortadella and smoked maple syrup is simple yet sublime—but this is the spot to visit for a glass of wine accompanied by water vistas.

ART & CULTURE

QAGOMA

Together, the Queensland Art Gallery (QA) and Gallery of Modern Art (GOMA) form Australia’s largest modern and contemporary art gallery. Roosting on Brisbane’s South Bank, the establishment showcases exemplary art from Australia, Asia and the Pacific, and, as such, has become a firm favourite among both locals and tourists. By day, world-class exhibitions such as Danish artist Olafur Eliasson’s Presence—beginning December 6th—take centre stage; after dark, expect illuminated theatrics as GOMA permanently projects an intense, multi-hued James Turrell artwork onto its facade.

SHOP

BrownHaus

The experience of entering the luxurious, travertine-clad space is as beautiful as the creations the jewellery studio constructs. The culmination of founder Drew Brown’s 25 years of refining his craft, fine jewels and elevated everyday pieces for both men and women captivate your gaze, each example formed with the utmost intention and care. Moreover, Brown is redefining traditional artisanship and service in a new, modern way, ensuring the flagship store is accessible and exciting in equal measure.

James Street Precinct

For shopping, dining or even just perfecting the time-honoured art of people-watching, James Street is a one-stop hub where fashion, cinema, design and dining converge in Fortitude Valley. Wandering through the streets, discovering fresh, and established, ventures is a cinch. Restaurants sAme sAme and Biànca (from the team behind Agnes and the new Idle bakery) are hard to pass up; next door, be prepared to queue for a cone at Gelato Messina. A recent arrival to the zone is Heidi Middleton’s Artclub atelier, while Australian tailoring brand P. Johnson recently launched its new store, designed by the renowned Tamsin Johnson, across from The Calile hotel.

WELLNESS

The Bathhouse Albion

In Brisbane is home to multiple wellness centres in which one can work out or unwind, such as the five-floor, $80 million TotalFusion Platinum Newstead. This facility, designed by architectural practice Hogg & Lamb, presents a more serene, temple-like experience in the once-industrial Albion Fine Trades district, delivering a communal yet luxe bathhouse with spa, cold plunge, sauna, float, and steam room. With a separate area for hydration spruiking organic TeaGood loose-leaf teas, an hour session ensures a restorative reset.

DAY TRIP

Lady Elliot Island

Visiting one of the most pristine sections of the Great Barrier Reef in one day from Brisbane? Yes, it is indeed possible—and in style, too. With an early start from Redcliffe, around 40 minutes’ drive from the city, take a 90-minute flight to the 45-hectare island and then indulge in a glass-bottom boat viewing, an island tour, and a guided snorkel where you will swoon over mesmerising coral and other-worldly marine life. Lunch is included.

You may also like.

Tropical Storm

Brisbane’s design-led renaissance is gathering momentum and redefining the city as a destination of distinction.

When it comes to the question of which Australian city can claim to be the country’s epicentre of cool, it’s always been a two-horse race between you-know-who. But challengers to the municipal hegemony do periodically raise their heads above the cultural parapet: Hobart has the world-class MONA in its corner; Perth flexes its white-sand beaches and direct flights to London; plucky Canberra enduringly punches above its weight, wielding a Pollock masterpiece or two at the National Gallery. Now, Brisbane— for decades ironically nicknamed “BrisVegas” as a jibe at its lack of places to see and be seen—is ready to assert itself as a serious contender to break the Sydney-Melbourne monopoly.

The Queensland capital is booming, buzzing and bougier than ever. In the past twelve months alone, Brisbane has seen the addition of $80 million ultra-luxe members’ wellness club TotalFusion Platinum, and earned a place on Condé Nast Traveller’s Hot List for hosting the second outpost of Andrew McConnell’s renowned restaurant Supernormal—both designed by Sydney-based multidisciplinary studio ACME. Since the latter’s opening, the upscale dining scene in the CBD—once steeped in starched white-tablecloth tradition—has come into its own with high-concept, slick and scene-y establishments you’ve likely already seen on Instagram.

Among them is Central, named Australia’s best-designed space at this year’s Interior Design Awards. The subterranean late-night dumpling-bar-meets-disco, designed by one-to-watch local firm J.AR Office, is bathed in bright white light and features a DJ booth built into the open, epicentral kitchen. A 10-minute walk along the river towards the Botanic Gardens reveals Golden Avenue, a buzzy collaboration between J.AR Office and Anyday, the Brisbane hospitality group behind some of the city’s most beloved restaurants of the last decade (Biànca, hôntô, sAme sAme, and Agnes). A skylit oasis where palm fronds cast slivers of shade over tiled tables laden with bowls of baba ganoush and clay pots of blistered prawns, the Middle Eastern-inspired eatery feels like Queensland’s answer to Morocco’s walled courtyard gardens.

That design-forward premises anchor much of the buzz around Brisbane’s new pulse points should come as no surprise. After all, this is an urban centre whose perception and personality were transformed in the 2010s by the brutalist breeze-block facades of the then-burgeoning James Street Precinct. Financed by local developers the Malouf family, and designed by Brisbane’s architecture power couple Adrian Spence and Ingrid Richards, the zone has become a desirable, nationally recognised address for flashy flagships and big-name boutiques (just ask Artclub’s Heidi Middleton and The New Trend’s Vanessa Spencer, who each unveiled plush piled-carpet stores along the strip in October).

But it wasn’t until the 2018 opening of The Calile Hotel that Brisbane truly shed its “big country town” image, staking its claim on the international stage. The Palm Springs-inflected urban resort—which, by now, surely needs no introduction—landed 12th in 2023’s inaugural World’s 50 Best Hotels ranking, ahead of Claridge’s and Raffles.

“That was really quite massive for the optics of what Brisbane has to offer the rest of Australia,” says Ty Simon, a born-and-bred Brisbanite and one of the four visionaries behind the Anyday group, along with his details-driven Milanese wife Bianca, executive chef Ben Williamson, and financial backer Frank Li. From that point on, the use of elite architects and designers became de rigueur across the enclave, weaving a sense of permanence into the local fabric. “We believe in what’s happening here,” says Marie-Louise Theile, creative director of the James Street Initiative and PR executive behind many of the city’s primo spots. “And we’re digging in.”

For in-demand Australian interior designer Tamsin Johnson, the mastermind behind some of James Street’s most carefully curated properties—including her husband Patrick Johnson’s P. Johnson Femme showroom, which opened in September—this momentum is “a wonderful thing”. Idle, Johnson’s August-launched first project with Anyday, is a prime example of what she calls a “contemporary sleekness” that feels intrinsic to the new mood taking hold in Brisbane. A modern-day answer to Milan’s 140-year-old gourmet emporium Peck, the site is a study in how mixed materials—glass, concrete, stainless steel and terrazzo—can create a sense of freshness with a 20th-century overtone.

It’s this dialogue between old and new, so intrinsic to Johnson’s work, that makes Brisbane such a compelling canvas for the Melbourne-born, Sydney-based creative. “I think Brisbane is striving hard for its own identity and voice in Australia, and it is clearly working,” she says. For Johnson, that evolution is also “a process of recognising what you have”, a nod to the strong bones the city has to work with and revisit. From the airy stilted Queenslanders to GOMA’s riverside glass pavilion and the subtropical modernism of Donovan Hill’s landmark C House, Brisbane’s design heritage is a quiet yet potent force, infused with what Johnson calls “the subtle memory of bucolic Australia”. Brisbane’s best contemporary architecture reflects what Richards and Spence described when designing The Calile as “a gentle brutalism”. It incorporates the style’s characteristic heaviness—concrete, rigid geometry and cavernous interiors—but, in response to the climate, does away with barriers between outside and in, and welcomes light, air and a feeling of weightlessness that creates spaces that feel open, relaxed and intimately connected to their surroundings.

Johnson will explore this language further in Anyday’s most ambitious venture yet: a four-level dining destination within the colonial-era Coal Board Building, just across from Golden Avenue. Its debut concept The French Exit—a wood-panelled brasserie with half-height curtains and a 2.00 am licence—is set to be unveiled by year’s end, ensuring the once-sleepy heart will beat well into the early hours.

Luring big names to lend the city their cool factor for one-off projects is one thing, but perhaps the most profound sign that Brisbane still bursts with promise is the fact that so many creative forces are choosing to stay, rather than take their talent elsewhere. “I never thought I’d still be in Brisbane,” laughs J.AR Office director Jared Webb, a local-for-life who started the firm in Fortitude Valley in 2022 after a decade spent working under Richards and Spence. “Trying to entice people to stay and see Brisbane as a city to live in, and to visit, is a big undertone of all our work on a much broader scale,” says Webb, whose designs rely heavily on steel, concrete and stone, both as a means to temper the tropical climate and evoke an aura of continuity he believes Brisbane’s built environment has lacked. (Once dubbed the demolition capital of Australia, the municipality lost more than 60 historic buildings during the ’70s and ’80s under former Queensland premier Joh Bjelke-Petersen, whose two-decade rule was recently revisited in a dramatised documentary available to stream on Stan).

Translating Brisbane’s current buzz into something lasting seems to weigh on the minds of many of the city’s creatives. Vince Alafaci, who forms one half of ACME with his partner Caroline Choker, shares this sentiment when reflecting on their design for Supernormal. “It’s about creating spaces that evolve with time, not ones that date,” he says. “We wanted every element to feel timeless—grounded, honest and enduring.” That pursuit of longevity is something Tamsin Johnson recognises, too: “It’s the people pushing for it that excite me the most. They’re committed,” she says, reflecting on the city’s creative ambition. “I think our designers, the most committed ones, want to leave landmarks and character, bucking against the trend of mundane, short-term and artless developments that all our capitals have experienced. And perhaps Brisbane is leading this mentality.”

You may also like.

Holiday Gift Guide

The supreme Christmas wish-list awaits—maximum impact guaranteed.

Consider this your definitive shortcut to Christmas morning triumph. From museum-grade jewellery to objects of quiet obsession, this is a wish-list calibrated for maximum impact and minimal guesswork. Each piece in this round-up earns its place not through novelty, but through craft, heritage and that elusive quality collectors recognise instantly: desire with staying power. There are icons reimagined (Piaget’s Andy Warhol watch, a masterclass in pop-era permanence), feats of mechanical bravado (Jacob & Co.’s globe-trotting tourbillon), and indulgences that turn ritual into theatre—whether that’s a Hibiki 21 poured just so, or a Rolls-Royce picnic staged like a state occasion. Fashion, design, fragrance and fine drinking are all represented, but united by a single premise: these are gifts that signal intention. The kind that linger on the mantelpiece, wrist or memory long after the wrapping paper is cleared. The stocking at robbreport.com.au, as ever, is generously—and ingeniously—stuffed.

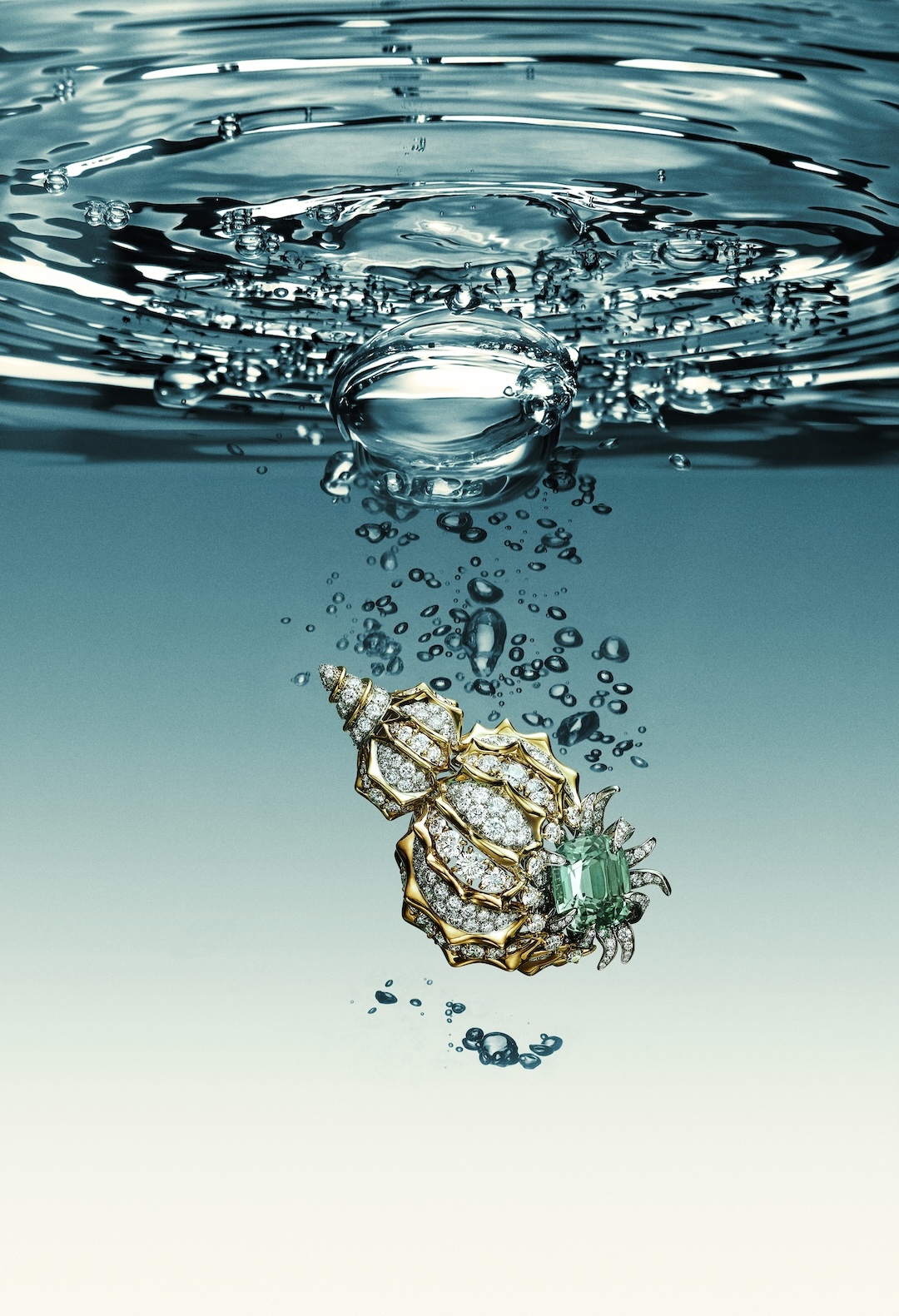

[main image, top] Tiffany & Co. Blue Book Collection Shell Green Tourmaline Brooch, POA; tiffany.com

Top Tip

Montegrappa limited edition 007 Special Issue fountain pen, $2,850, at The Independent Collective; theindependentcollective.com

Clear Winner

Alchemica ‘Transparent’ glass decanter, $1,000; artemest.com

Holding Court

Celine Halfmoon Soft Triomphe lambskin bag, $5,500; celine.com

Beauty and the Feast

Rolls-Royce picnic hamper, $59,676; rolls-roycemotorcars.com

Minutes of Fame

Piaget limited-edition Andy Warhol Watch Collage with 18-carat yellow gold caseback, $128,000; piaget.com

Fancy That

Graff High Jewellery fancy intense yellow oval, white oval and round diamond necklace, POA; kennedy.com.au

Momentos in Time

Christopher Boots Thalamos Keepsake trinket box, $859; christopherboots.com

Strapper’s Delight

Roger Vivier La Rose Vivier sandals in satin, $2,620; rogervivier.com

Sun Kings

Rimowa x Mykita Visor MR005 Aviator Sunshield, $940; rimowa.com

Take Your Best Shot

Hibiki 21 Year Old blended whisky, $1,399; kentstreetcellars.com.au

Making Perfect Scents

Creed Aventus, $559; creedperfume.com.au

Earth Hour

Jacob & Co. The World is Yours Dual Time Zone Tourbillon, $464,750; inspire@jacobandco.com.au

Glass Acts

Fferrone May coupe, $445 (set of two); spacefurniture.com

Fferrone May flute, $375 (set of two); spacefurniture.com

Worth the Wait

Masterson 2018 Shiraz. $1,000; available to order from the Peter Lehmann Cellar Door by calling (08) 8565 9555.

You may also like.

Radek Sali’s Wellspring of Youth

The wellness entrepreneur on why longevity isn’t a luxury—yet—and how the science of living well became Australia’s next great export.

Australian wellness pioneer Radek Sali is bringing his bold vision for longevity and human performance to the Gold Coast this weekend with Wanderlust Wellspring—a two-day summit running 25-26 October 2025 at the RACV Royal Pines Resort in Benowa. Sali, former CEO of Swisse and now co-founder of the event and investment firm Light Warrior, has long been at the intersection of wellness, business and conscious purpose.

Wellspring promises a packed agenda of global thought leaders in biohacking and longevity, including Sydney-born Harvard researcher David Sinclair, resilience pioneer Wim Hof, performance innovator Dave Asprey and muscle-health expert Gabrielle Lyon. From immersive workshops to diagnostics, tech showcases, and movement classes, Sali aims to make longevity less a niche pursuit for the elite and more an accessible cultural shift for all. Robb Report ANZ recently interviewed him for our Longevity feature. Here is an edited version of the conversation.

You’ve helped bring Wellspring to life at a moment when longevity seems to be dominating the cultural conversation. What drew you personally to this space?

I’ve always been passionate about wellness, and the language and refinement around how we achieve it are improving every day. Twenty years ago, when I was CEO of Swisse, a conference like this wouldn’t have had traction. Today, people’s interest in health and their thirst for knowledge continue to expand. What excites me is that wellness has moved into the realm of entertainment—people want to feel better, and that’s something I’ve always been happy to deliver.

There are wellness retreats, biohacking clinics, medical conferences everywhere. What makes Wellspring different?

Accessibility. A wellness retreat can be exclusive, but Wellspring democratises the experience. Tickets start at just $79, with options up to $1,800 for a platinum weekend pass. That means anyone can learn from the latest thought leaders. Too often in this space, barriers are put up that limit who can benefit from the science of biohacking. We want Wellspring to be for everyone.

You’re not just an organiser, but also an investor and participant in this field. How do you reconcile passion with commercial opportunity?

Any investment I make has to have purpose. Helping people optimise their health has driven me for two decades. It’s satisfying not just as an investor but as an operator—it builds wonderful culture within organisations and makes a real difference to people’s lives. That’s the natural fit for me, and something I want to keep refining.

What signals do you look for in longevity ventures to separate lasting impact from passing fads?

A lot of what we’re seeing now are actually old ideas resurfacing, supported by deeper scientific research. My father was one of the first in conventional medicine to talk about diet causing disease and meditation supporting mental health back in the 1970s. He was dismissed at first, but decades later, his work was validated. That experience taught me to look for evidence-based practices that endure. Today, we’re at a point where great scientists and doctors can headline events like Wellspring—that’s a huge cultural shift.

Longevity now carries a certain cultural cachet—its own insider language and status markers. How important is that to moving the field forward?

Health is our most precious asset, and people have always boasted about their routines—whether it’s going to the gym, doing a detox, or training for a marathon. What’s different now is that longevity practices are gaining mainstream recognition. I see it as something to be proud of, and I want to democratise access so everyone can ride the biohacking wave.

But some argue that for the ultra-wealthy, peak health has become a kind of luxury asset—like a private jet or a competitive edge.

That’s short-sighted. Yes, there are extremes, but most biohacking methods are accessible and inexpensive. Look at the blue zones—their lifestyle practices aren’t costly, yet they lead to long, healthy lives. That’s essential knowledge we should be sharing widely, and Wellspring is designed to do that in an engaging way.

Community is often cited as a key factor in healthspan. How does Wellspring foster that?

Community is at the heart of it. Just as Okinawa thrives on social connection, we want Wellspring to be a regular gathering place where people uplift each other. Ideally, it would become as busy as a Live Nation schedule—but for health and wellness.

Do you worry longevity could deepen class divides?

Class divides exist, and health isn’t immune. But in Australia, we’re fortunate—democracy and a strong equalisation process help maintain quality of life for most. Proactive healthcare, like supplementation and lifestyle changes, isn’t expensive. In fact, it’s cheaper than a daily coffee. That’s why we’re one of the top five longest-living nations. The opportunity is to keep improving by making proactive health accessible to everyone.

Some longevity ventures are described as “hedge-fund moonshots.” Others, like Wellspring, seem grounded in time-tested approaches. Where do you stand?

There’s value in both, but I’m more interested in sensible, sustainable practices. Things like exercise, meditation, and community-driven activities are proven to extend life and improve wellbeing. Technology can support this, but we can’t lose sight of the human elements—connection, balance, and purpose.

Finally, what role can Australia—and Wellspring—play in shaping the global longevity conversation?

The fact that we can put on an event like Wellspring, attract world-leading talent, and already have commitments for future years says a lot. Australia is far away, but that hasn’t stopped great scientists and thinkers from coming. We’ll be here every year, contributing to the global conversation and, hopefully, helping more people extend their healthspan.