Marrakech’s Most Glamorous Riad Just Added 10 Dazzling New Rooms

Take an excluisve tour of El Fenn’s lavish new interiors.

Related articles

Touring El Fenn with Vanessa Branson feels like bounding through her own home. She knows everyone here at the hotel she co-owns in Marrakech with three friends, joking with guests soaking up the sun on poolside recliners, leaping up the stairs excitedly as she shows off the 10 new rooms she’s just added. She describes them as “glorious.” And she’s not wrong.

Twenty years have passed since Branson, sister of Richard, and close friend Howell James bought a dilapidated riad in the Marrakech medina, thinking they were purchasing a small holiday home and not realizing that the sale came with a handful of equally run-down properties attached to it. Keen on an adventure, they opened it in 2004 as a six-room guesthouse. El Fenn’s now instantly recognisable formula of eye-popping colors combined with exquisite Moroccan craftsmanship, midcentury furniture and a dazzling collection of local and international art quickly earned the hotel a cult following. It feels like a place where you’re surrounded by those in the know—and you are. (Case in point: Madonna celebrated her 60th birthday here.)

The new addition, unveiled this month, brings the total to 42 rooms spread across 13 interconnected riads. The rooms are, according to Branson, the final stage of El Fenn’s evolution. But isn’t it tempting to keep going, absorbing even more riads and adding to the mesmerising world she’s created here?

“Forty-two rooms are the dream,” she says. “The staff can remember each guest by name—we don’t want to lose the home-away-from-home atmosphere.”

While there’s definitely a welcoming ambience, this is a place of dreams. El Fenn’s five tranquil colonnaded courtyards, inhabited by friendly cats and a family of tortoises, are filled with palms, citrus trees and cascading greenery. Come evening, candles bathe the spaces with warm, flickering light. There are swimming pools, oversized sofas and cozy nooks for lounging the days away. Billowing drapes provide shade on the terraces, as do the handmade straw hats that are scattered poolside.

The rooftop is one of the loveliest in Marrakech, home to a lively restaurant and bar with eye-popping views of the medina, surrounding minarets and, on a clear day, the Atlas Mountains. And the El Fenn boutique, with red walls, backgammon-esque black-and-white tiled floor and spiral staircase up to the roof, is filled with kaftans, cushions and other things of beauty that will let guests take a bit of El Fenn design inspiration back home.

But back to the new rooms. El Fenn’s owners worked with architect Sylvain Ragueneau and Moroccan craftsmen and women to give each its own completely individual identity. Expect vintage chandeliers, free-standing bathtubs and stained-glass elements, alongside the exquisite design details that are the result of incorporating generations worth of Moroccan craft heritage into the hotel. Some rooms are flooded with morning light; others receive the warm rays of the setting sun.

“No one room resembles another,” says Branson. “Each has a different hand-crafted stucco ceiling, handmade zellige tiles and polished tadelakt plaster walls.”

Tadelakt is what gives the new rooms their bursts of color, a type of lime plaster combined with pigments sourced in the medina that are mixed and applied by hand to the walls, then rubbed smooth with stones. A final application of olive oil soap adds the characteristic waterproof sheen.

With Branson being a gallerist, curator and founding president of the Marrakech Biennale, it’s no surprise that the contemporary art on display at El Fenn is a major draw in itself. The collection, one of the finest in Morocco, includes works by Sir Antony Gormley, South African artist William Kentridge and Moroccan sculptor Batoul S’Himi, as well as a newly commissioned work by renowned Moroccan visual artist Hassan Hajjaj. It all comes together beautifully to create a hotel that is unlike anything else that exists in the city.

“We’ve been growing oh-so-slowly for nearly 20 years,” says Branson. “Now is the time to consolidate and concentrate on the cultural role we play in Marrakech.”

Rooms at El Fenn start at approximately $720 per night.

Subscribe to the Newsletter

Recommended for you

Golden Touch

Discretion is the better part of glamour at the glittering Maybourne Beverly Hills.

October 9, 2024

White Lotus-ing? How Hit Films and TV Shows Are Inspiring Elite Travelers to ‘Set-Jet’ Across the Globe

It’s not just The White Lotus. Prestige TV and blockbuster films set in far-flung destinations are driving bookings like never before.

October 2, 2024

You may also like.

30/10/2024

You may also like.

Time Flies

Bugatti’s hybrid Tourbillon is the most powerful model in the marque’s history. And the coolest bit? An instrument cluster inspired by the finest Swiss horology.

First there was Veyron. Then came Chiron. Now Tourbillon. Bugatti’s new 1,800 hp (1,342 kW) hypercar delivers even more shock-and-awe than its predecessors. Gone is the famed 8.0-litre quad-turbo W16 engine. In its place is a new 1,000 hp (746 kW), 8.3-litre naturally aspirated V16 paired with a trio of electric motors delivering 800 hp (597 kW). That combination makes this the most powerful Bugatti ever.

While the design of the all-carbon-composite body is clearly derived from the signature lines of both the Veyron and Chiron, its roofline is lower, the body lighter and more aerodynamic, and that iconic horseshoe grille more imposing. Yet the likely headline feature will be the car’s all-new interior featuring a skeletonised, titanium-and-sapphire-glass instrument cluster inspired by Swiss watchmaking (for the uninitiated—“tourbillon” refers to the mechanical complication that increases accuracy in high-end timepieces).

Bugatti Automobiles S.A.S

“Beauty, performance, and luxury formed the blueprint for the Tourbillon. What we have created is a car that is more elegant, more emotive and more luxurious than anything before it,” stated Mate Rimac, Bugatti Rimac’s CEO, to Robb Report during an exclusive preview at the company’s newly opened design studio in Berlin.

He explained that, four years ago, when the Tourbillon concept was on the drawing board, there were multiple suggestions for what an all-new Bugatti might look like. Options included an SUV, a coupe-like crossover and a luxury four-door sedan. Then there was the choice of either a hybrid or all-electric power train. “The proposal to make it electric was the obvious choice. We had our [Rimac] Nevera, that we could easily transfer our technology and re-skin the body. But I felt it was wrong for Bugatti,” said Rimac. “I wanted a successor to the Veyron and Chiron, a true hypercar with a combustion engine. Our customers agreed.”

Bugatti Automobiles S.A.S

To create it, Rimac teamed with Cosworth, a renowned British engine builder, to help develop the naturally aspirated V16 mill. Designed to rev to 9,000 rpm, the engine offers a similar output as the original Veyron’s quad-turbocharged W16. To heighten the performance, Rimac and his team used their proven expertise in electric propulsion to pair the V16 with twin electric motors driving the front wheels, with a third at the rear. For battery power, a 25 kWh, oil-cooled 800-volt pack is integrated into the chassis and located behind the passengers. It’s powerful enough to give the Tourbillon a usable electric-only range of around 60 km.

As you would expect, the Tourbillon has been developed to be blisteringly fast. According to Emilio Scervo, Bugatti’s chief technical officer, early prototype tests suggest a rate of acceleration from zero to 100 km/h in 2.0 seconds, zero to 200 km/h in 5.0 seconds, and zero to 300 km/h in 10.0 seconds. Flat out, the max-speed target is 445 km/h, though with a speedometer that reads up to 550 km/h, we expect there’s more to come. “For us, it was important that the car retained the pure and raw analogue feel of a naturally aspirated combustion engine, while pairing it with the agility and ability provided by electric motors,” said Scervo.

The engine itself sits low in the Tourbillon’s new, super-stiff body structure, which is formed using next-generation T800 carbon composites. It features a forged-aluminium, multi-link suspension—front and rear—that replaces the previous double-wishbone steel setup used in the Chiron. The 3-D-printed aluminium suspension arms and uprights, and AI-developed, 3-D-printed hollow airfoil arm at the rear, are nothing less than pieces of art.

Bugatti Automobiles S.A.S

For the exterior lines, Frank Heyl, Bugatti’s director of design, explained that styling influences came from three landmark Bugattis of old: the Type 35 racer of the 1920s, the long Type 41 Royale built from 1927 through 1933, and the storied Type 57SC Atlantic from the 1930s. “The design focus was on Bugatti’s iconic horseshoe grille. It’s significantly wider and lower than in the Chiron, and it’s from which all lines of the car originate. It defines the car,” said Heyl, who added that another signature element is “the new central windshield wiper, which continues the line that starts on the hood and flows back along the roof. Just like on the Atlantic.” Set back from the grille are twin rows of wafer-thin LED lights. Between them is a narrow panel on the hood that raises up to reveal a “frunk” big enough for a set of custom-designed luggage.

In profile, the sweeping “Bugatti line” around the doors—a defining feature of both the Veyron and Chiron—looks even more striking with the car’s lowered roofline. At the rear, huge exhausts, a Le Mans–style carbon-fibre diffuser (twice the size of that on the Chiron), and a rolling wave of LED lights featuring illuminated “Bugatti” lettering, add to the visual drama. And to allow onlookers to gaze at that V16 power plant—and for cooling purposes—the engine sits open to the elements.

Robb Rice

Upon opening the dihedral “scissor” doors and entering the cockpit, you’re presented with arguably the new Tourbillon’s most dramatic feature; a skeletonised instrument cluster inspired by the art of Swiss watchmaking. Made up of more than 600 components, it’s constructed from titanium with sapphire-glass faces and detailing that incorporates rubies.

The three-dial cluster is fixed in place, with the twin spokes of the flat-bottom steering wheel rotating around it. The unit is constructed, in-house, to remarkable horological tolerances of 50 microns—the average cross-section of a human hair. The entire cluster weighs just 709 g. Cascading down from the middle of the fascia is the centre console featuring crystal glass that’s formed over 13 separate stages to ensure strength and clarity. The aluminium elements are anodised and milled from a single block.

A close-up of the Bugatti Tourbillon’s 1,000 hp, 8.3-liter naturally aspirated V-16 engine.

The Tourbillon’s 1,000 hp, 8.3-liter naturally aspirated V-16 engine is paired with three electric motors.

Robb Rice

To add a little theatre to firing-up that big V16, there’s a prominent center-console aluminium knob that you pull to start, and push to turn off. It’s another nod to Bugatti models of yesteryear. What you won’t see, however, are any touchscreens. Heyl believes that the primary element that dates a car is an oversized screen. “What was state-of-the-art 10 years ago, is now ugly,” said Heyl. “The Tourbillon is designed to be timeless.”

In Bugatti tradition, the Tourbillon will also be highly exclusive. Only 250 examples are planned, each starting at around $6.3 million. The first customer cars are scheduled to be built at Bugatti’s atelier in Molsheim, France, starting in 2026.

Bugatti Automobiles S.A.S

“Yes, it is crazy to build a new V16 engine, to integrate it with a new battery pack and electric motors, and to have 3-D-printed suspension parts and a real Swiss watchmaker instrument cluster,” noted Rimac. “But it is what Ettore Bugatti would have done.”

You may also like.

For Dubai, the Time Is Now

The bustling Middle Eastern city is emerging as an important hub for serious watch collectors

Tucked away in a corner of the Dubai International Financial Centre, near the Ritz-Carlton, is Perpétuel Gallery, an unassuming 1,200 m² boutique displaying some of the world’s most important independent watchmaking. During Dubai Watch Week—a biannual event run by the Seddiqi family, the most prominent watch retailers in the UAE—the shop, just a few minutes’ walk from the fair in the DIFC, held its own exhibition that was filled to the brim with the watchmakers themselves, from Roger W. Smith to Simon Brette to Rémi Maillat of Krayon. There, holding court, was Hamdan Bin Humaid Al Hudaidi, a distinguished collector who founded Perpétuel in 2021, in the middle of the Covid pandemic.

“I never thought I would take my passion professionally, ever,” he tells Robb Report. “Everyone was against the idea because they were very certain this would fail.” How wrong they were. Instead, Perpétuel has become one of the most significant global players in connecting and brokering deals between collectors and their indie idols. As a serious client himself, Al Hudaidi has unique relationships that allow him to create limited editions exclusive to the gallery—quite a feat when you consider the waiting lists for some of the watchmakers in question are a decade or more long. A recent collaboration of 15 limited-edition Krayon Anywhere watches with desert-orange accents sold out to clients—not just in the Middle East, but also in Australia, the US and South Africa.

Courtesy of Perpétuel Gallery

It’s proof positive of the area’s booming and influential watch scene. Many credit Dubai Watch Week—and by extension the Seddiqi family—for the fervent local interest in watch collecting. When the event launched in 2015, it was small, hosting just 15 brands, mostly independents. “It was really a project to give back to the industry,” says Hind Abdul Hamied Seddiqi, director general of the event and CMO and communications officer for Ahmed Seddiqi & Sons, “but also to educate the general public that the watch industry is not as intimidating as you think.” It’s a strategy that has paid off. Last year’s edition ballooned to 60 brands, including big-name players such as Rolex, Audemars Piguet and Van Cleef & Arpels, along with nearly 24,000 attendees, the largest crowd to date.

Despite the draw, the five-day-long public event has an easygoing appeal that other watch fairs often lack. One can spot Philippe Dufour perched outside a pavilion smoking a pipe, Kari Voutilainen enjoying an alfresco lunch, or Rexhep Rexhepi in line for an espresso. It’s an exceedingly rare chance for collectors to mingle with the masters in a relaxed space where everyone is in a jovial mood thanks to the casual atmosphere and balmy weather—and Seddiqi plans to keep it that way. “I worry if we go bigger, we’ll lose this feeling of intimacy,” she says. “I have a lot of people asking me to commercialise the show, but it’s just going to ruin the whole vibe.”

Courtesy of Perpétuel Gallery

The explosion of interest isn’t just for new timepieces: vintage is also having its moment. Historically, the Middle East hasn’t been receptive to “used” goods, but recent years have reflected a shift in perspective. Tariq Malik, cofounder and managing partner of Momentum, also located in the DIFC, just a three-minute walk from Perpétuel, was an early pioneer in the area when he opened shop in 2011. In the beginning, he says, it would be common for someone to look at his wares and ask if he was selling “used” watches. “I said, ‘It’s vintage,’ and they said, ‘Oh, wow.’ When I would say ‘vintage’ they would start pulling out their camera and taking photos. We brought vintage to Dubai, so it was a new thing.” He’s now sought-after by clients both in the UAE and internationally for his allotment of rare Rolexes, with a specialisation in Day-Dates and hard-to-find Stella and stone dials.

Al Hudaidi also dabbles in vintage, predominantly ultra-rare Pateks—one might walk into Perpétuel and find him casually pulling a full-set Ref. 2499 third series from a coffee-table drawer. Naturally, that watch has sold along with two other full-set 2499s, but a unique Patek Philippe Ref. 1491J chronograph from the ’40s is still up for grabs (at press time, anyway). It was made by the Stern family for Jimmy Powers, an American boxing commentator during the era.

“I got goosebumps when I heard his voice on YouTube,” says Al Hudaidi. “I was like, ‘Oh, my God—that timepiece was his. And his name is engraved on the back!”

You may also like.

6 Ways Technology Will Transform Your Private-Jet Experience in the Next Decade

Extreme leisure or full-throttle engagement? The private-jet cabin of the future will offer both.

Within a decade, private-jet cabins could make even today’s cutting-edge interiors seem ancient by comparison. From digital skylights and smart seats to eye-tracking functionality and immersive soundscapes, the array of innovative amenities could transform even the longest flights into time well spent. Here, six areas in which technology will take the onboard experience to new heights.

Screen Time

Within three to five years, some private jets may have select windows replaced with curved, high-definition 4K OLED displays connected to live video feeds from the aircraft’s exterior. Imagine a cabin ceiling that morphs into a conservatory with a spectacular view of the moon, or full-height windows that present the landscape below with incredible fidelity. Information overlays are easy additions, but consider that these built-in visual portals could also double as insane gaming screens.

Seat Change

E-textiles will transform the next generation of jet seats into intuitive in-flight spa recliners. Sensors within the fabric will note your size, weight, pressure distribution, and body temperature, then rely on their A.I.-driven processors to, say, heat the seat before you realise you’re chilly or massage that kink in your back without being asked. Powering themselves by converting body heat into electricity, the chairs might also know to widen and recline when you nod off.

Seeing the Light

Chronobiological lighting to mitigate jet lag will comprise organic light-emitting diode (OLED) panels, capable of creating 16.3 million different light combinations, to reset a passenger’s internal clock as they traverse time zones. Eventually, such panels will migrate from light fixtures to smart fabric on the ceiling, resulting in more diffuse illumination that allows for near-infinite options across the colour spectrum.

And there are many other applications. For example, OLED displays, as wide as a piece of paper, can be used to digitally transform the entire wall of the cabin’s colour, texture or scene. It is called projection mapping, and it will make changing the wall color from hot pink to a textured crocodile leather as easy as changing your computer screen saver. As Ingo Wuggetzer, vice president of cabin marketing for Airbus, explains, light literally creates spaces, giving cabin designers a highly versatile and easily customisable digital canvas.

Higher Management

The ability to access basic audio or video from your smartphone is here, but imagine faster, streamlined connectivity that lets you manage video conferencing, heating, mood lighting, window shades, service requests, even a steriliser—from a single app. According to Airbus’s Wuggetzer, next-gen digital architecture will turn personal spaces into individual “ecosystems” controlled by each passenger. Tim O’Hara, director of completions research and development at Gulfstream, notes that eye-tracking technology could allow you to interact with the app via virtual screen, meaning you don’t even have to lift a finger.

Breaking the Sound Barrier

Rosen Aviation has developed a new onboard audio system with Laurence Dickie, designer of the famed Bowers & Wilkins Nautilus loudspeaker. According to Rosen’s Lee Clark, the goal is to go from today’s audio equivalent of “a 1970s eight-track” to what he refers to as “Elvis, six feet away, singing to you”—a soundscape that only you will hear, delivered by headrest speakers and haptic drivers in the seat. Meanwhile, Bongiovi Aviation intends to employ transducers embedded in the jet’s interior side panels, eliminating the need for traditional speakers altogether. The advantages are numerous, and it allows airframers to reduce cabin weight and fully utilise space while eliminating traditional speakers from the design.

Bringing movie-theater audio quality to aviation is already available. Dolby Atmos puts you inside the movie or song as it is playing. In collaboration with Dolby, SkyCinema Aviation was the first to create an Atmos-enabled processor built for business jets to compensate for cabin altitude and jet noise. The result? You will clearly hear the car approaching from a half mile away in that famous scene of the 1959 Hitchcock classic North by Northwest, just as the director intended.

Hands Free

With full showers, skylights, and large vanities gracing the lavatories of the most luxe business jets today, what could be next? The smart lavatory is evolving into a nearly completely hands-free space by incorporating sensors to activate everything from faucets to showers. Using an AI algorithm, Diehl Aviation has taken it a step farther to add more functionality with voice-controlled commands for opening and closing the door, turning on lights, and activating water. Hologram light switches will eventually keep the lavatory completely hands free, while smart mirrors can multitask by providing an interactive display of digital content.

You may also like.

30/10/2024

George Hamilton’s Rules for Timeless Style

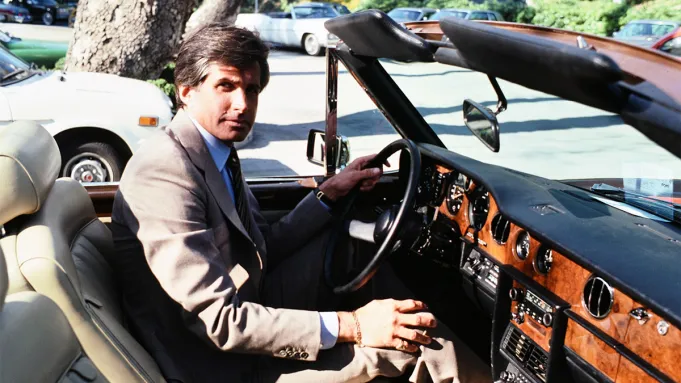

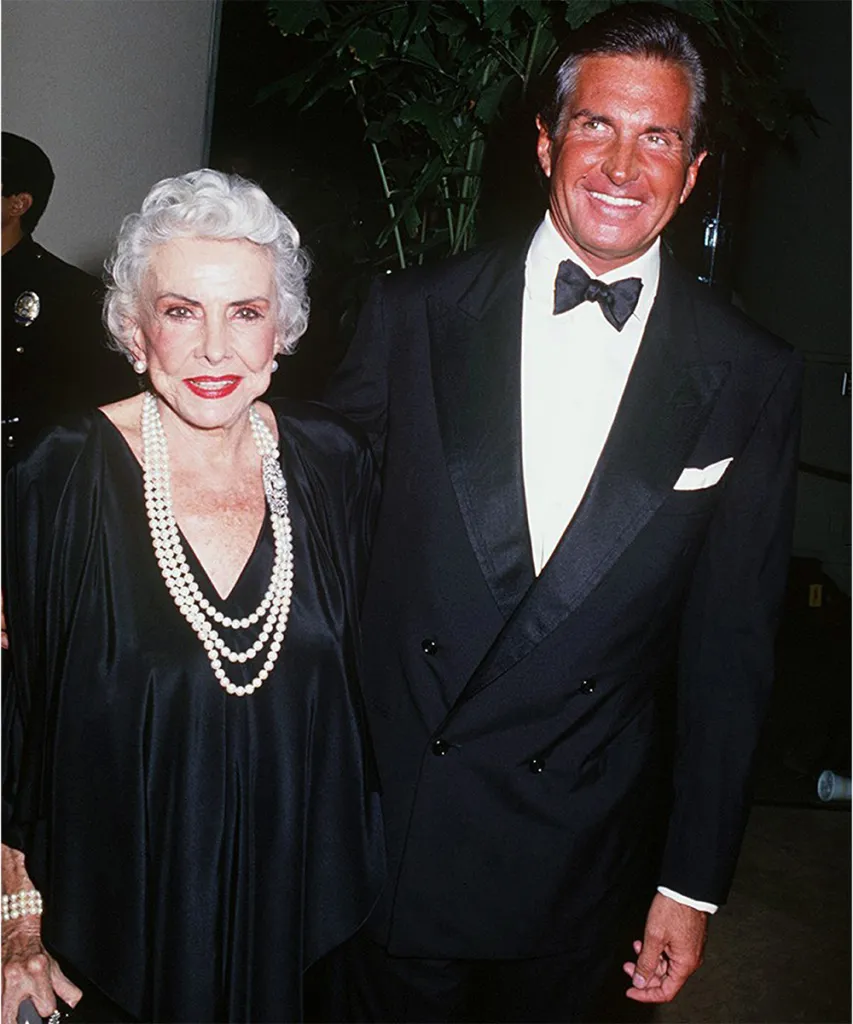

The Hollywood icon continues his conversation with Robb Report, touching on manners, tailoring, and La Liz.

So riveting was my chat last week with George Hamilton and his tailor, Paolo Martorano, that I decided to continue my conversation with the actor in a second installment this week. Despite the grey sky and steady drizzle falling outside the windows of my New England home, Hamilton’s sunny demeanor had me feeling more like I was in Palm Beach, cool drink in hand and clad in a coral linen ensemble. And almost two hours later, it was apparent why he has earned the icon status he enjoys.

Hamilton is, by all standards, larger than life: a charming gentleman and a style legend who epitomises Hollywood at its most glamorous. Generously candid, his humour is rivalled only by his sincerity. Amid stories from his childhood, of his A-list costars and insights he’s gleaned throughout his life, Hamilton offers a masterclass in true masculinity, with a sharply attuned acuity for what women want and a practiced understanding of what makes a gentleman—with or without a bespoke tailor at one’s service.

“A man should look confident and capable, and those two things reside between the waist and the shoulder. Because if the waist is nipped in a little, it means he’s in good shape. If the shoulder is robust, he can handle the problem.”

George Hamilton

The Language of Suiting

The question is an all too common one: how does one define “gentleman?” It’s an elusive proposition and fodder for countless think pieces, none of which can rival Hamilton’s estimation: “I think a man should always look as though he’s able to handle the problem, if need be,” he says, though his mind can’t resist turning to tailoring.

“A man should look confident and capable, and those two things reside between the waist and the shoulder. Because if the waist is nipped in a little, it means he’s in good shape. If the shoulder is robust, he can handle the problem,” says Hamilton.

Getty

We joke about the scourge of skinny suits and discuss the value of a good tailor, though he was adamant that a man does not need a bespoke bank account to pull off bespoke style, suggesting that young men look to the prep aesthetic and pair a smart made-to-measure sport coat with a gray flannel trouser. “It makes a young man look incredibly well dressed and without too much study.” It’s the prerogative of an older man, too, he says to keep yourself looking good. “When you finally get your head together, your ass is falling apart,” he says with a warm laugh.

No matter the age, he insists the principles of good dressing remain the same. In addition to proper jacket proportions, pants should serve to elongate the leg and be complemented by well made shoes. “What is it you’re selling? You’re selling you,” he says. “Not the suit. Not the shoes. Not the socks. A great tailor doesn’t make you look like you’re wearing a costume. It blends into you, it makes you look great. That’s the whole trick. They have to subordinate their ego a little bit to make you look better. But when they do it right, it makes everyone want to look like that. And then the tailor becomes the one who’s the architect.”

“When you finally get your head together, your ass is falling apart.”

-George Hamilton

Well Groomed

Grooming is also paramount, a show of respect for yourself and the people around you. The cologne Hamilton wears is one he’s spent sixty years getting just right. From taxi drivers to female companions, everyone is completely intrigued by it—and its name is the one thing in our conversation he demurs on. According to Hamilton, a man’s grooming routine should fit in a dopp kit and tend toward restraint. “Whether it be a manicure, a pedicure, or the right haircut, it must be simple and to the point,” he says. “We’re meant to be out killing dragons while the woman’s getting ready. But it doesn’t mean that it needn’t be sophisticated.”

Getty

He credits his mother with much of his style instinct and one story in particular illustrates the precarious balance of intentional elegance and ease. “I remember the first time I was going out to dinner at a debutante thing in New York, and I got all dressed up. I stood at the door and she said, “What are you doing? You’re standing there like you’re a waiter.” You should get on the floor and play with the dog, with your tuxedo, with your dinner clothes.” So I got on and played with the dog. When I got up, she said, ‘Now, that’s the way you should stand. That’s the way you go.” I never forgot that.”

Manners Maketh the Man

It’s not just Hamilton’s style sense that hinges on balance. “Men can’t give up kindness to be strong,” he says. “Strength without kindness or kindness without strength—it won’t work. There’s a balance to it.”

Again, he attributes his upbringing for these values. “I was raised in an era that had manners, and those manners were the lubricant for all problems,” he says. “If you live long enough and you travel enough, and if you churn in the right company, civility is the ability to keep everything oiled and proper so that you don’t bump up against things.”

For Hamilton, manners are defined by what all people you encounter have to say about you once you’ve left their company: the compliments you pay people when you have nothing to gain, nothing transactional to incentivise you. “The way you treat people that the world might not deem important? That denotes or connotes who a person really is.”

Getty

Hamilton also says humour is imperative. “I don’t take myself seriously, or any of it seriously. And most people do,” he says. “But life is over so fast – and it’s hard to have a sense of humour, but if you have that, it saves you. It’s the shock absorber for everything.”

And critically, despite a man’s station in life, humility is a defining mark of character. Put simply: no one likes a show off. “You don’t have to flaunt it,” he emphasises. “We all have to learn the basic rules of life and you don’t have to go around explaining to everyone that you know and you are better. I don’t think that’s attractive for a man or a woman really. But I think a woman appreciates a kind of quiet confidence.”

What Women Want

Those glints of humanity, of fallibility, are imperative when it comes to romance and seduction. “You have to have a human touch to it all, I think. Not always being perfect, it’s sometimes the imperfect that makes it a human quality that makes it. And sometimes, you can’t display it, you have to betray it,” Hamilton says.

Just ask Elizabeth Taylor.

When Taylor was playing Cleopatra, Hamilton says, they were in England shooting. The weather was horrible and the studio had already sunk millions of dollars into the production. Finally, they cast Richard Burton to play opposite Elizabeth Taylor as Mark Antony. “They were working on a scene where she’s supposed to say, “I haven’t dismissed you,” Hamilton recounts. “And Richard had been drinking for two or three days, and was exhausted. He had no sleep.” He told Taylor he needed coffee. They brought it to him, but he couldn’t bring the cup to his mouth. “So he asked her if she would lift the cup to his mouth so he could drink. And she said that’s when she fell in love with him.”

Getty

Taylor sought security her whole life—a product of growing up a child actress with others always reliant on her. “She wanted someone to take charge, because she never had that as a child,” he says, noting that it was Mike Todd, who he believes was her most compatible match in that regard.

But not to be outdone, Hamilton and his gentlemanly ways left their own imprint on Taylor’s life. “Elizabeth was extraordinary,” he says. “But she was like a little girl, kind of lost. And she always had a list of things she needed, ten or twelve things.” The two were staying together at a hotel in New York when George asked her to write down her list of “necessities” for him. “She sat down and lingered over the list for an hour, getting it together and worrying about it. And I took it downstairs to the manager of the hotel, Bernard Lackner. And I asked Bernard, “Can you take this list of things that Elizabeth Taylor needs and get them done?’ “Of course,” Lackner said. “15 minutes later, everything would be done.”

Very modestly, George tells me he didn’t so much manage the list himself, but he knew how to delegate. Still, it impressed Taylor all the same. Hamilton returned to their room, list completed and delivered the good news to Taylor.

“I’ve never met a man like you who incredibly took charge and handled everything,” Taylor said. Here’s to men who can get the job done.

You may also like.

30/10/2024

Meet the Women Who Run the World’s Most Iconic High-Jewellery Ateliers

Names like Nathalie Verdeille and Claire Choisne are giving decades-old designs a modern appeal. Here’s how.

Men have dominated high-jewellery design for centuries, but no longer. Female creatives have now risen to the uppermost echelons of the world’s elite houses, bringing with them an unprecedented approach both technically and philosophically.

They are creating the jewellery of the future—thinking of new ways to wear pieces, working with innovative new materials, and going above and beyond the DNA of their houses while still incorporating those time-tested codes. Due in part to the massive investment required to make high jewellery, the category has rarely seen innovation until now. New technologies, forward-thinking minds, and a changing cultural landscape are allowing for a new era in the category. Meet the personalities upending the industry.

Boucheron | Claire Choisne

A tall, soft-spoken, and ethereal figure in a black column gown, Claire Choisne personally greeted guests as they entered a softly lit space within Boucheron’s Place Vendôme headquarters in June. They were there to take in the Parisian house’s latest head-spinning array of futuristic jewellery for its Carte Blanche collection as Choisne, the creative director behind the avant-garde pieces, detailed how they were made, gently explaining their extreme technicality. Her designs are so complex, she started a team dedicated solely to innovation research in 2018. “At the beginning, I was scared that people wouldn’t understand,” says Choisne. “And year after year, I understood: A woman who buys a nice couture dress with something creative doesn’t want something boring. She can be open to something more interesting.”

“Interesting” is putting it mildly; the room was filled with wearable art. Palladium-finished aluminium epaulets crafted like waves crashing over shoulders, a nearly five-foot-long diamond-drop necklace evoking ice formations, and a collar necklace fashioned from rock-crystal discs adorned with 4,542 diamonds that glittered like ripples of water were just a few of the masterpieces on display.

If that sounds cool, it’s just a taste of what Choisne has been whipping up lately at the 166-year-old jewellery house. Unrivalled in her inventiveness—a sort of mad scientist of high jewellery—she has created necklaces made with holographic coatings more typically seen on aviation-runway lights as well as with Aerogel, a material used by NASA to capture stardust.

Carte Blanche translates to Blank Slate, which could be read as a reference to Choisne’s unorthodox approach. She grew up in the South of France in a family that didn’t care about jewellery. By the time she graduated the Rue du Louvre jewellery college, she was as interested in technique as in design. At 24 years old, she went to work for independent Parisian jeweler Lorenz Bäumer. “It was quite crazy, because at the beginning I was alone creating pieces for Chanel [under Bäumer], which I did for eight years,” Choisne says. He later enlisted her to help him design jewellery for Louis Vuitton for four years, and they also collaborated on fragrance projects. “It was really good training to create Chanel in the morning, perfume in the afternoon, and so on,” she says. “I was in charge of the studio, the technical parts, and buying the stones—almost everything.”

It’s that level of experience that has given her the know-how to turn her unprecedented designs into reality. The Ondes necklace alone took more than 5,000 hours to produce. And yet she works on four to five collections at a time, which means she’s designing four to five years ahead. But given how outrageously forward-thinking her pieces always feel when released, she’s probably much further along in her head.

Her latest mic drop? The Quatre 5D Memory ring, revealed in September in New York at a celebration for Boucheron’s new Madison Avenue boutique, uses 5D optical data storage—a nascent technology developed by Peter Kazansky, a professor at the University of Southampton and chief science officer at SPhotonix—that theoretically can preserve vast amounts of data for billions of years in a tiny space made of nanostructured glass. Choisne collaborated with the French Institute for Research and Coordination in Acoustics/Music to use 5D memory crystal to encode a musical composition into the white-gold, diamond, and silica-glass ring. “It’s not for everybody,” she concedes. “It’s not the little black dress, you know? You already have the little black dress, and you need something else.”

Cartier | Marie-Laure Cérède

“One of my earliest memories of jewellery is a gold ring my parents gave me when I was 8 years old,” says Marie-Laure Cérède, creative director of watches and jewellery at Cartier. “I grew up in Africa, and gold jewellery was a part of everyday life—accessible and beautifully crafted.” Her father worked for the French government in Gabon, and though she lost the ring while swimming in the Atlantic Ocean off the coast of Libreville, she says its twisted golden thread has kept her dreaming of the perfect knot ever since. Of course, one of Cartier’s most recognizable designs is its Trinity ring—three intertwining bands in white, rose, and yellow gold—but Cérède says that, while it’s important to her to allude to Cartier’s history in its present-day collections, she wants to “be inspired by everything but Cartier.”

Her design philosophy certainly seems to be working: Cérède’s pieces simultaneously hark back to the storied house while being wildly imaginative. Take a diamond, onyx, and moonstone brooch (below) that cleverly forms the shape of a claw—a clear reference to the French house’s perennial Panthère mascot—with a single talon lifting open to reveal a secret watch beneath. Meanwhile, a carabiner covered in diamonds and accented with multicolored gems nods to late Cartier designer Aldo Cipullo’s fascination with hardware, while presenting an entirely new way of wearing jewelry; the piece, which also doubles as a clock, is meant to dangle from one’s belt loop.

Rethinking how jewellery is worn is a pivotal theme in today’s changing landscape and a trend that’s due as much to our era’s casual dress codes as to its shifting gender norms. “The carabiner could easily be for a woman or a man,” says Cérède, adding that a male buyer attached it to his suit pants for a gala. She also notes that clients are now wearing jewellery not just for special occasions but also in everyday life—and it’s changing how she designs: “We have to think about the volume and the intimacy of the product in relation to the wearer.” This approach is most pointedly reflected in a pair of sunglasses she created for the Cartier Libre Polymorph collection, adorned along the frame and stems with coral, emeralds, diamonds, and onyx. Incredibly, the jewels can transform into a tiara or a pair of earrings. “I think there is a new segment where there’s so much space to do the kind of pieces which are not classic, not only in the design but also in the way they are worn,” she says.

Cérède cut her teeth in both the communications and the creative-product-development sides of the business at Cartier, which could explain her knack for dreaming up pieces that tell a story. Her rise to the top of Cartier’s creative kingdom started out like modern postgrad lore: After receiving a degree in business and marketing from the elite ESCP Business School, she attended a talk by a Cartier executive that so captivated her, she boldly asked for an internship. “That person’s love for jewellery sparked something in me, and I knew I had to be a part of it,” she recalls. Following an almost seven-year stint at Cartier, she spent 12 years at Harry Winston as artistic director before returning to the French house in 2016.

After decades in the industry, Cérède believes it’s the clients that have changed the most. “They have developed a sharper knowledge of jewellery, especially younger generations, partly thanks to social media,” she says. “I see this as very positive, as it makes culture—both iconic and creative—more universal.” It also makes competition much fiercer. Fortunately for Cartier, Cérède is proving that a leopard can indeed change its spots.

Louis Vuitton | Francesca Amfitheatrof

Francesca Amfitheatrof has an uncanny ability to create a hit. Exactly one year after her 2013 arrival at Tiffany & Co., she launched the hugely successful Tiffany T collection and was responsible for repositioning the Blue Book series to elevate the brand’s status in high jewelry. Her Midas touch soon caught the eye of Bernard Arnault, who poached her to lead Louis Vuitton’s watches and jewellery division as artistic director—a full three years before he would acquire Tiffany for almost $24 billion. Since 2018, she has been working her magic at Vuitton, deftly weaving its omnipresent monogram into high-impact and technically savvy jewellery that feels simultaneously edgy and regal.

It’s no small feat to make a 128-year-old logo look fresh season after season—particularly in high jewellery, where the monetary stakes are far greater than in clothing or handbags. “I think it is tricky, right?” says Amfitheatrof. “These pieces are meant to be masterpieces that will last forever. And how do you treat them in a way that they are beautiful in their own right, but they become recognisable as Vuitton?” She has achieved that equilibrium by approaching the LV and fleur-de-lis motifs in a graphic and sculptural way, so that they blend into the architecture of the pieces, balancing minimalism with maximalism—alongside bonafide expertise in metalworking and stones—to create jewellery that feels both serious and fun. Take, for example, the Splendeur necklace: a structural and transformable high collar crafted with a woven mesh of flowers carved in 18-karat yellow gold and set with diamonds and 52 rubies—the largest number ever used on a single piece at the house. With more than 2,400 elements, it required 17 gem setters, 30 jewellers, and 3,217 hours of work.

Her ability to tune in to the global zeitgeist could be attributed to her exotic childhood. Born in Tokyo, she spent parts of her youth in New York City, Moscow, and Rome, as well as at boarding school in Kent, England. “My mother is Italian, from Rome, and they are big jewellery wearers—they wear a lot of gold and they’re not shy about wearing jewellery,” says Amfitheatrof, perched on a rooftop against a vivid-blue Mediterranean backdrop in July. Her grandmothers on both sides, she says, also had nice jewellery. Her father, who served as the Moscow bureau chief for Time in the ’80s, had wanted his daughter to attend Harvard, but, she says, “I refused to take my SATs.” After she earned an undergraduate degree from Central Saint Martins and a master’s from the Royal College of Art, a gallery show of her silver vases and jewellery at Jay Jopling’s White Cube gallery led to her exhibiting jewellery at the Parisian trade show Tranoï, where major retailers including Browns in London, Maxfield in L.A., and Colette in Paris all picked up her collection. Soon she was designing jewellery for everyone from Balenciaga to Chanel to Fendi.

Within the workshops of these powerhouse names, she honed her approach to the craft. “I’ve made jewellery in America, I’ve made jewellery in Italy, and I’ve made jewellery in France,” she says. “Each country has its own traditions, and sometimes you have to push against those to say, ‘No, actually, we want to do it at this thickness,’ or ‘We want to do it at that height,’ or ‘I want the diamonds to have more light on them.’ ” She is said to be meticulous about details—expecting as much rigor from those who work for her as she does from herself. “When I interview my team, if they have a Pinterest board, they’re not going to be the right people,” Amfitheatrof says. “I think that real depth of knowledge comes from studying and from experience. It can’t all come from social media or an app.”

Tiffany & Co. | Nathalie Verdeille

Since joining Tiffany & Co. in 2021, when she was lured by Bernard Arnault from the house’s archrival Cartier, Nathalie Verdeille has preferred to remain behind the scenes. Notoriously press-shy, she has done very few interviews of any kind since being tapped to head creative design for the multibillion-dollar jewellery business acquired by LVMH in 2021. Even after agreeing to participate in this story, she declined to answer any questions about her formative years or how she landed in the industry.

But her work speaks volumes. In just three years, the Parisian designer has elevated the American house’s famous Blue Book collection of high jewellery through painstaking and highly technical work, amping up motifs established by the late Tiffany designer Jean Schlumberger. The famed jeweller’s ornate ’50s and ’60s pieces were favorites of the era’s “ladies who lunch,” but Verdeille and Tiffany have been putting a new spin on the aesthetic by pumping up the architectural volumes and the craftsmanship, as well as the stone selection.

Her riffs on well-known Schlumberger styles add a subtle edge that’s more powerful than prim. A highlight of this year’s Céleste collection, for example, is the Iconic Star necklace, set with free-form sky-blue aquamarines in an unusual array that resembles clouds, punctuated with cerulean-hued zircons and stars fashioned from diamonds and mother-of-pearl. Meanwhile, Verdeille has given Tiffany’s classic Bird on a Rock brooch—recently adopted as red-carpet attire by Robert Downey Jr., Jay-Z, and other sharply dressed men—a serious infusion of funky hues, such as a turquoise-headed bird with a diamond and pearl body perched on a vivid-orange fire opal. “Seeing things differently and pushing that vision to its full potential is crucial for me,” Verdeille says. “Often, a slight variation on a classic can make all the difference and infuse modernity into the design. Anchoring the signature motif in the hearts of those who appreciate our work is crucial.”

Courtesy of Tiffany & Co.

In other words, she’s no stranger to reimagining history. “My way of designing is inspired by the grand fundamentals of jewellery, a practice refined through training with the greats in traditional Parisian jewellery workshops,” she tells Robb Report. After graduating from the Haute École de Joaillerie in Paris in 1997, she went to work for Lorenz Bäumer (who also trained Claire Choisne of Boucheron), helping the independent designer create jewellery for many of the historical brands on the Place Vendôme, the centre of high jewelry in the City of Light. She landed briefly at Cartier before heading to Chaumet—a company known for creating jewels, particularly tiaras, for European royalty—for three and a half years. In 2005 she returned to Cartier, where she further sharpened her skills at refreshing centuries-old traditions through challenging craftsmanship, before landing in the U.S. to head America’s crown jewel, Tiffany.

In Verdeille’s case, a revamp doesn’t mean an entirely new visual language, but rather an elevation of workmanship that would have been impossible technically in Schlumberger’s era. Take the Wings necklace from the Céleste collection: It’s visually arresting without looking wildly out-of-the-box. And yet, it’s “among the most complex pieces we have designed,” Verdeille says. Each element of the necklace was crafted individually over 1,732 hours because of its intricate structure, varied diamond shapes, and the difficulty posed by the density, hardness, and high melting point of platinum. Collectors will recognise the wing motif from Schlumberger’s 18-karat-yellow-gold and diamond earrings that mimic the plumes of a bird’s wings, but Verdeille imparts the 2024 Blue Book necklace with high drama that leaves the old version in the dust. She may prefer to remain out of the spotlight, but her high-wattage pieces can’t help but shine.

Messika | Valérie Messika

Diamonds are deeply embedded in Valérie Messika’s roots. Her father, André, is a prominent stone dealer who supplies high-quality gems to some of the leading industry houses. But when she fell into the fold of the family business in 2000, she had a different vision: Instead of selling stones to be set by the heritage houses on the Place Vendôme, she wanted to dream up her own, much hipper jewellery.

“At the time, I thought there wasn’t any brand that could speak about diamonds in a cool way, in a very easygoing way for everyday that you can buy for yourself as a woman, not waiting around for an engagement ring,” she says. So, in 2005, still in her mid-20s, she founded her own namesake brand.

Messika set about creating the kind of pieces she wanted to wear. Starting with high fine jewellery, she developed her signature Move collection, based on a diamond-accented oval with a sliding diamond in the centre. In 2012 she debuted her first high-jewellery set, which showed off the calibre of stones that made her family a mint in the wholesale business, but in an arena that put the Messika name on a new stage. Recent collections have included everything from a disco-ready choker adorned with an offset 20.04-carat pear-cut yellow diamond next to a 9.07-carat cushion-cut diamond—modelled by former first lady of France Carla Bruni, in 2023—to a collar necklace set with 2,400 snow-set diamonds punctuated by a 3.55-carat pear-shaped yellow diamond and styled on supermodel Natalia Vodianova this year. Forget ball gowns: Vodianova appeared in the ad campaign wearing skintight black PVC leggings, pointed stilettos, and a casual cardigan to echo the necklace’s neo-’80s vibe.

Courtesy of Messika

Messika’s penchant for fashion dates to her childhood, when she was enthralled by haute couture; she now gets involved in styling the advertising shoots. “I’m really obsessed by it,” she says. “It’s the perfect balance between the jewellery, the woman, and the outfit.” To that end, she has operated her business more like a high-octane fashion brand than a buttoned-up high-jewellery maison. She has even done collaborations, including two with Gigi Hadid and one with Kate Moss, who lent her bohemian eye to create diamond-encrusted headpieces, arm bracelets, and anklets.

But the name is catching on beyond paid endorsements. It seems that every cool girl in Paris has been seen in a Move bracelet, and celebrities from Rihanna to Irina Shayk have chosen to wear the high jewellery on the red carpet. Some are clients. (Beyoncé owns a custom-made choker with a 17-carat pear-shaped diamond from the French house.) Much of the fandom can be equally attributed to the modern designs and to Messika’s own exuberant personality. Now, with flagships in Los Angeles, Miami, and New York City, she has set her sights on conquering the U.S. market. “We have so many other steps to reach, because it’s a giant market,” Messika says. “But I can definitely feel that it’s our time. If we press the button, the market is ready to open, to be open to a newcomer in jewellery and high jewellery like us.” Consider it the Messika movement, in full swing.

You may also like.

30/10/2024