Robb Read: The Price Of Happiness

Our culture glorifies fortune building while warning that money won’t buy contentment (there’s always going to be someone, somewhere, with more). But must the two be mutually exclusive?

Related articles

The late Edgar Bronfman Sr., the billionaire CEO of the Seagram empire, once said he prayed every time he boarded his private jet. Not particularly afraid of flying, he wasn’t imploring God to spare his life in this gravity-defying contraption. Rather, his prayer was an act of gratitude: he was thanking the dear Lord he didn’t have to fly commercial. “If I’m going to be miserable, I’d rather be miserable rich than poor,” he quipped.

Wealth, undeniably, has its benefits. It provides not just cool stuff and superior health care but also freedom, control, choices—epitomised by the en masse flight of affluent New Yorkers and other urbanites to their vacation homes when the coronavirus pandemic struck. It’s no coincidence that the number-one thing people think will make them happy is money. They are mistaken. More on that later, but consider that Finland, a nation with just six billionaires (and about that many hours of daylight in winter), has ranked as the happiest country in the world three years in a row. Still, the connection between wealth and happiness is more complex than one might think. The surprising murkiness of money’s emotional impact has led a growing number of academics—psychologists but also economists—to study the subject in depth, and many a therapist to specialise in the troubled psyches of the well-to-do.

Experts tend to define happiness in two ways: in-the-moment joy (“My team just won the World Series!” “This is the best ice cream I’ve ever had!”) and overall life satisfaction (“I love my career, family and home and feel content”). No one disputes that living in poverty is a significant obstacle to achieving either definition, for a host of reasons. But after basic needs such as housing, food, education and health care are met, experts differ on money’s role.

Many academics point to research that shows, yes, the richer, the happier, but also that the resources required to jump to each subsequent level of contentment keep increasing. A boost in joy still follows a raise or other windfall, but the climb slows the wealthier you get. In other words, Jeff Bezos most likely no longer feels much of a thrill each time Amazon stock has a good day.

Then again, maybe he does. Sonja Lyubomirsky, a professor of psychology at the University of California, Riverside, and one of the foremost scholars of happiness, says there’s definitely a correlation between money and happiness—“if you make a million dollars a year, you’re generally happier than someone who makes 500,000, and that person is happier than someone who makes 250”—but it’s a two-way street. “Whenever people talk about money and happiness, they’re always assuming that money causes happiness,” she explains. “But the other causal direction is really important. Research shows that if you’re happier, you’re more likely to get a good job and accrue more income over your lifetime.” As she posits, most employers are more likely to hire a smiling, upbeat job applicant than a sullen one.

Lyubomirsky notes that wealth’s conferred “status and respect,” among other pluses, can be offset by negatives, such as the stress of running a company, the headache of spoiled kids or the failure to appreciate life’s simple pleasures. “You’d still rather the problems of too much money than too little, but certainly there are many problems associated with having a lot of money. They lower the correlation between money and happiness,” she says. “If money didn’t bring its own set of problems, richer people would be a lot happier, but they’re only a little happier.” Indeed, one remarkable study found that lottery winners were hardly more joyful than non-winners and only 33 per cent more so than people who had been paralysed in accidents. Moreover, they derived less enjoyment from quotidian activities—eating breakfast, chatting with a friend—than either of

the other groups.

Another respected scholar of happiness, Catherine A. San-der-son, professor of psychology at Amherst College, is sceptical of any correlation, noting that income has climbed steeply over the past 60 years but the proportion of people who are “very happy” has held steady. The issue, she says, is what social scientists call the “hedonic treadmill,” meaning, quite simply, that we get used to additional cash all too quickly. The buzz wears off. In addition, she asserts, people with higher earnings tend to spend less time on activities that bring them joy and more time in the pursuit of yet more riches.

One of the biggest reasons money fails to trigger more happiness, many experts agree, is that with a higher net worth come higher aspirations.

Sanderson points to what she calls the “wealthy-neighbourhood paradox”: Having worked hard and “made it,” you move into that fancy neighbourhood you’ve fantasised about, only to feel dejected. “ ‘I have a house in the Hamptons, but I wish I had a beach house in the Hamptons,’ ” she says, though the trappings of envy can also be cars, vacations, private schools. “The challenge with money is that it’s never enough. There’s no end point.” Sanderson cites a quote attributed to Theodore Roosevelt: “Comparison is the thief of joy.”

Surprisingly, the solution isn’t to compare “downward,” to those perceived as having less of something, as Lyubomirsky had assumed when she undertook her first research project at Stanford University, where she earned her PhD. “I was completely wrong,” she says. Interviewing Stanford undergrads, she discovered that the happiest ones compared neither up nor down, regardless of the qualities they were assessing. “They just didn’t compare. Unhappy people are constantly ruminating and comparing. Convincing yourself that other people are worse off is not a great strategy for happiness. Now, gratitude is.”

Judy Ho deals with both ends of the financial spectrum, studying low-income, marginalised and ethnically diverse populations as an associate professor at Pepperdine University, and treating extremely affluent patients, including celebrities and other public figures, as a clinical neuropsychologist in private practice. Depression and other mental illnesses, she says, are the result of biology, environment and life experience. The prosperous, she adds, are no less likely to be depressed than the unemployed. “Some people who are unemployed are not depressed,” Ho says. “Then there are people who have all the money in the world and are depressed because they feel inferior to their brother, who’s the CEO: ‘Everybody thinks I’m an idiot.’

“No matter who you are, how much money you have,” she continues, “there is always an opportunity to compare yourself to someone better.” For some, trying to measure up can be motivating; for others, a cause of despair.

The Harvard Study of Adult Development, a one-of-a-kind research project begun in 1938, initially enrolled 268 Harvard sophomores (including President John F. Kennedy) and later signed up 456 adolescent boys from inner-city Boston, then regularly conducted medical tests and in-person interviews with the two cohorts through the decades and into the new millennium (it eventually added spouses and now, with most of the original subjects deceased, has graduated to their children). Over the course of 80 years, and contrary to popular assumption, the study found that more than wealth or social class, more than IQ or fame or even genes, the greatest predictor of happiness—and even of physical and mental well-being—was strong relationships, whether with spouses, children or friends.

Harvard’s conclusions about relationships could explain why other studies find that one of the most effective ways to extract happiness from dollars is by purchasing shared experiences (such as a family vacation) or shareable objects (like a boat for outings). They also might point to the reason some in the highest financial demographic are melancholy.

Though Lyu-bo-mir-sky says high achievers overall are more confident and secure, some clinical psychologists note that a subset of this cohort are extremely insecure in their personal lives, frequently worrying that their romantic partners, children or friends do not genuinely love them.

“Their deepest fear is, ‘The minute I stop making money, they’re going to leave me,’ ” Ho says.

If it offers any solace to those with such trust issues, Sanderson points to the results of another study: while straight women overwhelmingly preferred wealthy romantic partners, they selected men who’d sold a dot-com rather than won the lottery. Earned wealth, in other words, was seen as an indicator of brains, drive or other qualities they admired.

With our culture’s reverence for making money, the wealthy who seek help for depression or anxiety can develop a unique brand of shame, especially if they sense they’re living in a bubble and feel they don’t deserve to be sad. “They can be just as emotionally damaged or more,” says Darby Fox, a therapist in private practice in Manhattan, among other locations. “You have the expectation that if you have a lot of things, shouldn’t you be happy?”

But Gretchen Rubin, a popular happiness guru with best-selling books (The Happiness Project, The Four Tendencies), a podcast and video courses to her name, cites research that finds happiness is probably 50 per cent genetic. “Clearly some people are just more anxious,” regardless of circumstance, she says, but can work to change their mindsets.

“Maybe the way worry works is you have 100 worry points total, and you allocate,” says Michael Norton, a professor at Harvard Business School with a Ph.D. in psychology. “When you get money, your worries change and you allocate differently. But you still worry the same amount.”

Anyone in doubt of our propensity for misery need look no further than the plethora of high-end in-patient treatment centres specialising in substance abuse and featuring pastoral settings, tasteful furniture and well-equipped gyms. At Milestones Ranch Malibu, where the recommended stay is 90 days, clients generally fall into three categories: CEOs and other accomplished professionals, celebrities and young-adult offspring of the very affluent. In addition to the internal demons they’re battling, some patients have to deal with dependent relatives and business associates who are anxious to get them back to work, according to Milestones CEO and executive director Denise Klein. The pressure on musicians or actors, who can feel responsible for the livelihoods of entire casts and crews, can lead them to abbreviate their time in treatment. “With cancer, you’re not going to cut chemotherapy short,” she says.

The offspring of the well-to-do, Klein says, tend to be flailing, a result of too much pampering and too little responsible parenting. “At least 80 per cent of the time, money is a factor in that they have been protected from consequences,” she says. Some come from families in which the parents are self-made and think they’re doing their kids a favour by absolving them of work. Instead, “they just don’t develop.”

Klein offers a case study of one recent success story. Alex (his name and some details have been changed) had amassed three DWIs by the time he was 21. His parents’ solution for the first two: hire a pricey lawyer to get him off. “He would wreck a Range Rover; he would get a Tesla,” Klein says. “It was replacing vehicles instead of any accountability.”

After the third arrest, Alex wound up at Milestones, where he received counselling for over a year. Turned out Alex had a flair for food. He landed a job at a top restaurant—his first employment of any kind—and, having found his element, was promptly promoted.

In the sphere of adolescent issues, such as substance abuse and acting up, Lyubomirsky says, “you have the biggest problems with the very poor and the very rich.” But it’s the latter whose families can afford private therapy, making the problems of moneyed progeny practically a specialty in their own right. Fox says family issues typically boil down to “an inability to communicate and connect”. “People think, ‘I’m giving you everything. Shouldn’t that be enough?’ Well, no, it’s not,” she says, adding that while daily life might be easier, relationships are not. (And on the subject of giving, Lyubomirsky says that parents would be wise to emulate Warren Buffett’s estate-planning philosophy: leave your kids “enough money so that they would feel they could do anything, but not so much that they could do nothing.”)

Fox echoes Klein’s emphasis that young adults find self-worth and resilience in employment. And while some parents are uncomfortable discussing finances at the dinner table, she strongly recommends starting at an early age by telling children what things cost and teaching them the difference between need (they’ve outgrown their old sneakers) and want (the latest sneakers are really cool), as well as demonstrating philanthropy. Most important, she adds, is to focus on character. “Turn the lens on who you are

as opposed to what you have,” Fox says.

In the same vein, Sanderson, the Amherst professor, advises accomplished parents to consider their kids’ personalities and passions and not push their own hard-charging career paths on them or hold up “wealth as a measure of intelligence”. She recounts a brunch at her eldest child’s elite prep school, where she mentioned to their table that she thought he’d make a great high-school teacher. One parent leaned over and opined, “Oh, he’s so bright. He could do so much better.” Sanderson was appalled. “For me, it was like, being a teacher would be so meaningful,” she says. (Not to mention he’d have summers off.) But, she laments, parents all too often let status and bragging rights get in the way.

What remains to be seen is how the psychology of money will change in the post-Covid world. Prior to the pandemic, there was already a yawning gap in the joyful experiences people could afford, but many of life’s daily irritants were equal-opportunity afflicters. Or as author Laura Vanderkam, who specialises in time management, puts it, “Whether you earn half a million a year or $50,000, you’re still stuck in traffic on your way to work.”

But the pandemic has cast a glaring spotlight on the stark differences, with the prosperous living what look to the struggling middle and working classes like vacations, in well-appointed homes with multiple freezers, ample outdoor space, swimming pools and live-in help. “When adversity hits—illness, divorce—people with wealth are buffered. That’s always been true,” Lyubomirsky says. “This is just a global example.”

Although most in the upper class are cushioned against economic downturns, Ho says some could be feeling the heat of business failures. “When there’s a threat that it might go away, it rips into their self-esteem,” she says. “ ‘Who am I if I’m not this person who makes a ton of money?’ ”

Gretchen Rubin, who blasts her followers daily uplifting quotes from Zora Neale Hurston and the like, says she has sensed more reflection and gratitude of late. “Some people feel they don’t have the right to experience personal loss given what’s happening,” she explains. “Wealth is like health. When we have it, it’s easy to take for granted and not think about it. These things matter much more in the negative.”

This piece is from our new Summer Issue – on sale now. Get your copy or subscribe here, or stay up to speed with the Robb Report weekly newsletter.

Subscribe to the Newsletter

Recommended for you

The Ultimate Guide to Pairing Wine With Spicy Food

What to drink when your favorite cuisine brings the heat.

Here’s What Goes Into Making Jay-Z’s $1,800 Champagne

We put Armand de Brignac Blanc de Noirs Assemblage No. 4 under the microsope.

By Mike Desimone And Jeff Jenssen

April 23, 2024

You may also like.

You may also like.

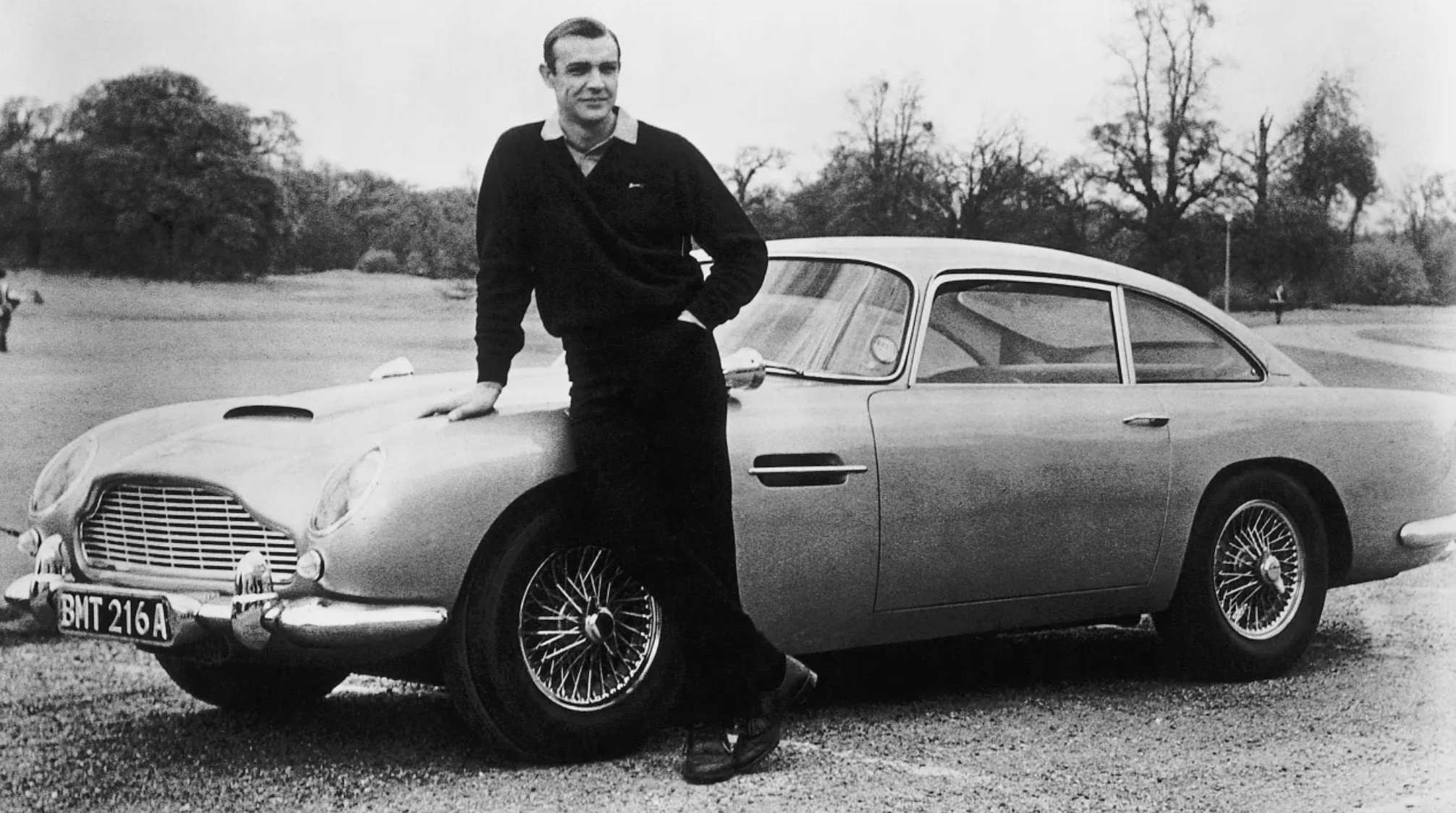

8 Fascinating Facts You Didn’t Know About Aston Martin

The British sports car company is most famous as the vehicle of choice for James Bond, but Aston Martin has an interesting history beyond 007.

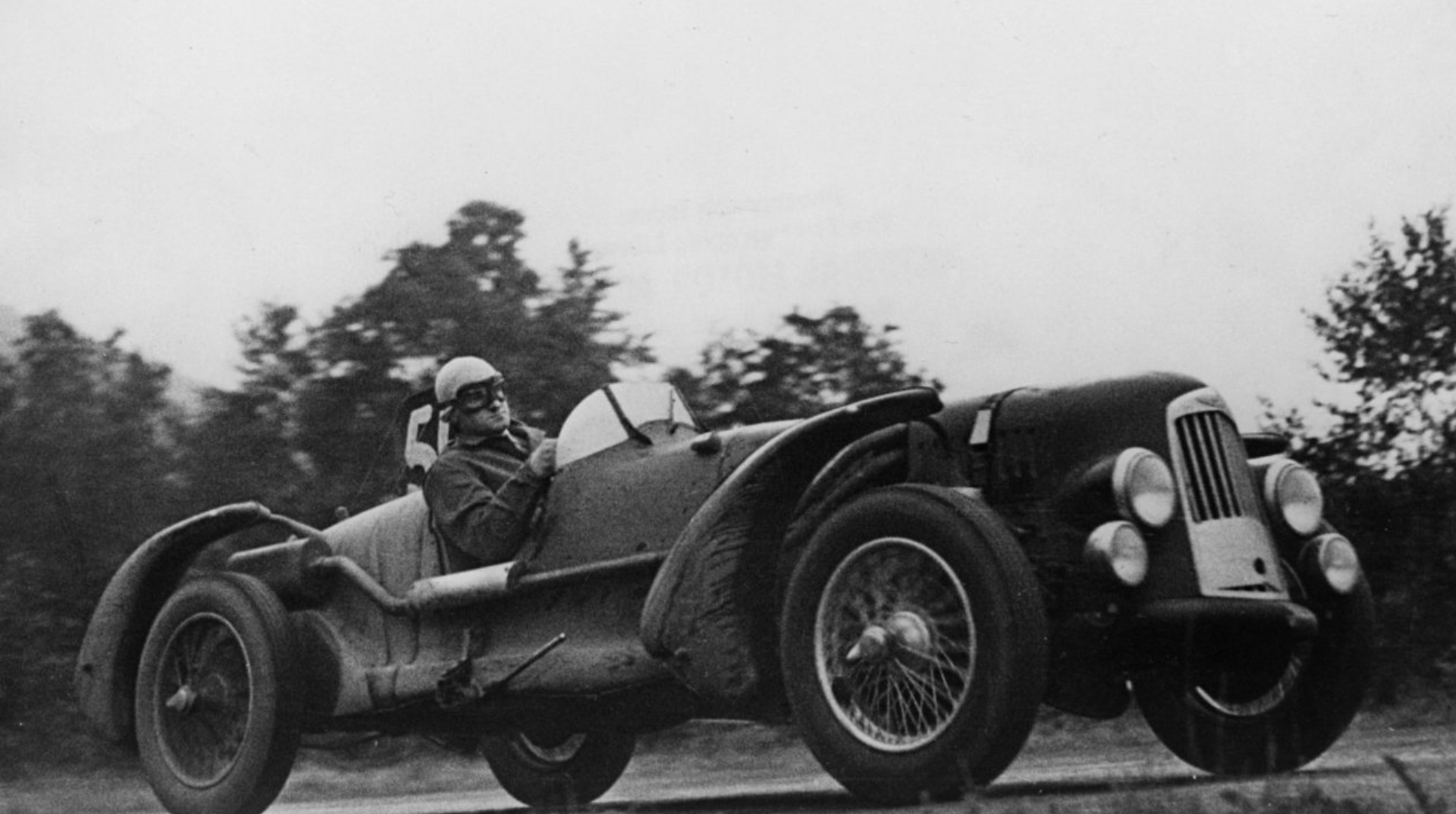

Aston Martin will forever be associated with James Bond, ever since everyone’s favourite spy took delivery of his signature silver DB5 in the 1964 film Goldfinger. But there’s a lot more to the history of this famed British sports car brand beyond its association with the fictional British Secret Service agent.

Let’s dive into the long and colourful history of Aston Martin.

You may also like.

What Venice’s New Tourist Tax Means for Your Next Trip

The Italian city will now charge visitors an entry fee during peak season.

Visiting the Floating City just got a bit more expensive.

Venice is officially the first metropolis in the world to start implementing a day-trip fee in an effort to help the Italian hot spot combat overtourism during peak season, The Associated Press reported. The new program, which went into effect, requires travellers to cough up roughly €5 (about $AUD8.50) per person before they can explore the city’s canals and historic sites. Back in January, Venice also announced that starting in June, it would cap the size of tourist groups to 25 people and prohibit loudspeakers in the city centre and the islands of Murano, Burano, and Torcello.

“We need to find a new balance between the tourists and residents,’ Simone Venturini, the city’s top tourism official, told AP News. “We need to safeguard the spaces of the residents, of course, and we need to discourage the arrival of day-trippers on some particular days.”

During this trial phase, the fee only applies to the 29 days deemed the busiest—between April 25 and July 14—and tickets will remain valid from 8:30 am to 4 pm. Visitors under 14 years of age will be allowed in free of charge in addition to guests with hotel reservations. However, the latter must apply online beforehand to request an exemption. Day-trippers can also pre-pay for tickets online via the city’s official tourism site or snap them up in person at the Santa Lucia train station.

“With courage and great humility, we are introducing this system because we want to give a future to Venice and leave this heritage of humanity to future generations,” Venice Mayor Luigi Brugnaro said in a statement on X (formerly known as Twitter) regarding the city’s much-talked-about entry fee.

Despite the mayor’s backing, it’s apparent that residents weren’t totally pleased with the program. The regulation led to protests and riots outside of the train station, The Independent reported. “We are against this measure because it will do nothing to stop overtourism,” resident Cristina Romieri told the outlet. “Moreover, it is such a complex regulation with so many exceptions that it will also be difficult to enforce it.”

While Venice is the first city to carry out the new day-tripper fee, several other European locales have introduced or raised tourist taxes to fend off large crowds and boost the local economy. Most recently, Barcelona increased its city-wide tourist tax. Similarly, you’ll have to pay an extra “climate crisis resilience” tax if you plan on visiting Greece that will fund the country’s disaster recovery projects.

You may also like.

Omega Reveals a New Speedmaster Ahead of the Paris 2024 Olympics

Your first look at the new Speedmaster Chronoscope, designed in the colour theme of the Paris Olympics.

The starters are on the blocks, and with less than 100 days to go until the Paris 2024 Olympics, luxury Swiss watchmaker Omega was bound to release something spectacular to mark its bragging rights as the official timekeeper for the Summer Games. Enter the new 43mm Speedmaster Chronoscope, available in new colourways—gold, black, and white—in line with the colour theme of the Olympic Games in Paris this July.

So, what do we get in this nicely-wrapped, Olympics-inspired package? Technically, there are four new podium-worthy iterations of the iconic Speedmaster.

The new versions present handsomely in stainless steel or 18K Moonshine Gold—the brand’s proprietary yellow gold known for its enduring shine. The steel version has an anodised aluminium bezel and a stainless steel bracelet or vintage-inspired perforated leather strap. The Moonshine Gold iteration boasts a ceramic bezel; it will most likely appease Speedy collectors, particularly those with an affinity for Omega’s long-standing role as stewards of the Olympic Games.

Notably, each watch bears an attractive white opaline dial; the background to three dark grey timing scales in a 1940s “snail” design. Of course, this Speedmaster Chronoscope is special in its own right. For the most part, the overall look of the Speedmaster has remained true to its 1957 origins. This Speedmaster, however, adopts Omega’s Chronoscope design from 2021, including the storied tachymeter scale, along with a telemeter, and pulsometer scale—essentially, three different measurements on the wrist.

While the technical nature of this timepiece won’t interest some, others will revel in its theatrics. Turn over each timepiece, and instead of a transparent crystal caseback, there is a stamped medallion featuring a mirror-polished Paris 2024 logo, along with “Paris 2024” and the Olympic Rings—a subtle nod to this year’s games.

Powering this Olympiad offering—and ensuring the greatest level of accuracy—is the Co-Axial Master Chronometer Calibre 9908 and 9909, certified by METAS.

A Speedmaster to commemorate the Olympic Games was as sure a bet as Mondo Deplantis winning gold in the men’s pole vault—especially after Omega revealed its Olympic-edition Seamaster Diver 300m “Paris 2024” last year—but they delivered a great addition to the legacy collection, without gimmickry.

However, the all-gold Speedmaster is 85K at the top end of the scale, which is a lot of money for a watch of this stature. By comparison, the immaculate Speedmaster Moonshine gold with a sun-brushed green PVD “step” dial is 15K cheaper, albeit without the Chronoscope complications.

—

The Omega Speedmaster Chronoscope in stainless steel with a leather strap is priced at $15,725; stainless steel with steel bracelet at $16,275; 18k Moonshine Gold on leather strap $54,325; and 18k Moonshine Gold with matching gold bracelet $85,350, available at Omega boutiques now.

Discover the collection here

You may also like.

Here’s What Goes Into Making Jay-Z’s $1,800 Champagne

We put Armand de Brignac Blanc de Noirs Assemblage No. 4 under the microsope.

In our quest to locate the most exclusive and exciting wines for our readers, we usually ask the question, “How many bottles of this were made?” Often, we get a general response based on an annual average, although many Champagne houses simply respond, “We do not wish to communicate our quantities.” As far as we’re concerned, that’s pretty much like pleading the Fifth on the witness stand; yes, you’re not incriminating yourself, but anyone paying attention knows you’re probably guilty of something. In the case of some Champagne houses, that something is making a whole lot of bottles—millions of them—while creating an illusion of rarity.

We received the exact opposite reply regarding Armand de Brignac Blanc de Noirs Assemblage No. 4. Yasmin Allen, the company’s president and CEO, told us only 7,328 bottles would be released of this Pinot Noir offering. It’s good to know that with a sticker price of around $1,800, it’s highly limited, but it still makes one wonder what’s so exceptional about it.

Known by its nickname, Ace of Spades, for its distinctive and decorative metallic packaging, Armand de Brignac is owned by Louis Vuitton Moët Hennessy and Jay-Z and is produced by Champagne Cattier. Each bottle of Assemblage No. 4 is numbered; a small plate on the back reads “Assemblage Four, [X,XXX]/7,328, Disgorged: 20 April, 2023.” Prior to disgorgement, it spent seven years in the bottle on lees after primary fermentation mostly in stainless steel with a small amount in concrete. That’s the longest of the house’s Champagnes spent on the lees, but Allen says the winemaking team tasted along the way and would have disgorged earlier than planned if they’d felt the time was right.

Chef de cave, Alexandre Cattier, says the wine is sourced from some of the best Premier and Grand Cru Pinot Noir–producing villages in the Champagne region, including Chigny-les-Roses, Verzenay, Rilly-la-Montagne, Verzy, Ludes, Mailly-Champagne, and Ville-sur-Arce in the Aube département. This is considered a multi-vintage expression, using wine from a consecutive trio of vintages—2013, 2014, and 2015—to create an “intense and rich” blend. Seventy percent of the offering is from 2015 (hailed as one of the finest vintages in recent memory), with 15 percent each from the other two years.

This precisely crafted Champagne uses only the tête de cuvée juice, a highly selective extraction process. As Allen points out, “the winemakers solely take the first and freshest portion of the gentle cuvée grape press,” which assures that the finished wine will be the highest quality. Armand de Brignac used grapes from various sites and three different vintages so the final product would reflect the house signature style. This is the fourth release in a series that began with Assemblage No. 1. “Testing different levels of intensity of aromas with the balance of red and dark fruits has been a guiding principle between the Blanc de Noirs that followed,” Allen explains.

The CEO recommends allowing the Assemblage No. 4 to linger in your glass for a while, telling us, “Your palette will go on a journey, evolving from one incredible aroma to the next as the wine warms in your glass where it will open up to an extraordinary length.” We found it to have a gorgeous bouquet of raspberry and Mission fig with hints of river rock; as it opened, notes of toasted almond and just-baked brioche became noticeable. With striking acidity and a vein of minerality, it has luscious nectarine, passion fruit, candied orange peel, and red plum flavors with touches of beeswax and a whiff of baking spices on the enduring finish. We enjoyed our bottle with a roast chicken rubbed with butter and herbes de Provence and savored the final, extremely rare sip with a bit of Stilton. Unfortunately, the pairing possibilities are not infinite with this release; there are only 7,327 more ways to enjoy yours.

You may also like.

Bill Henson Show Opens at Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery

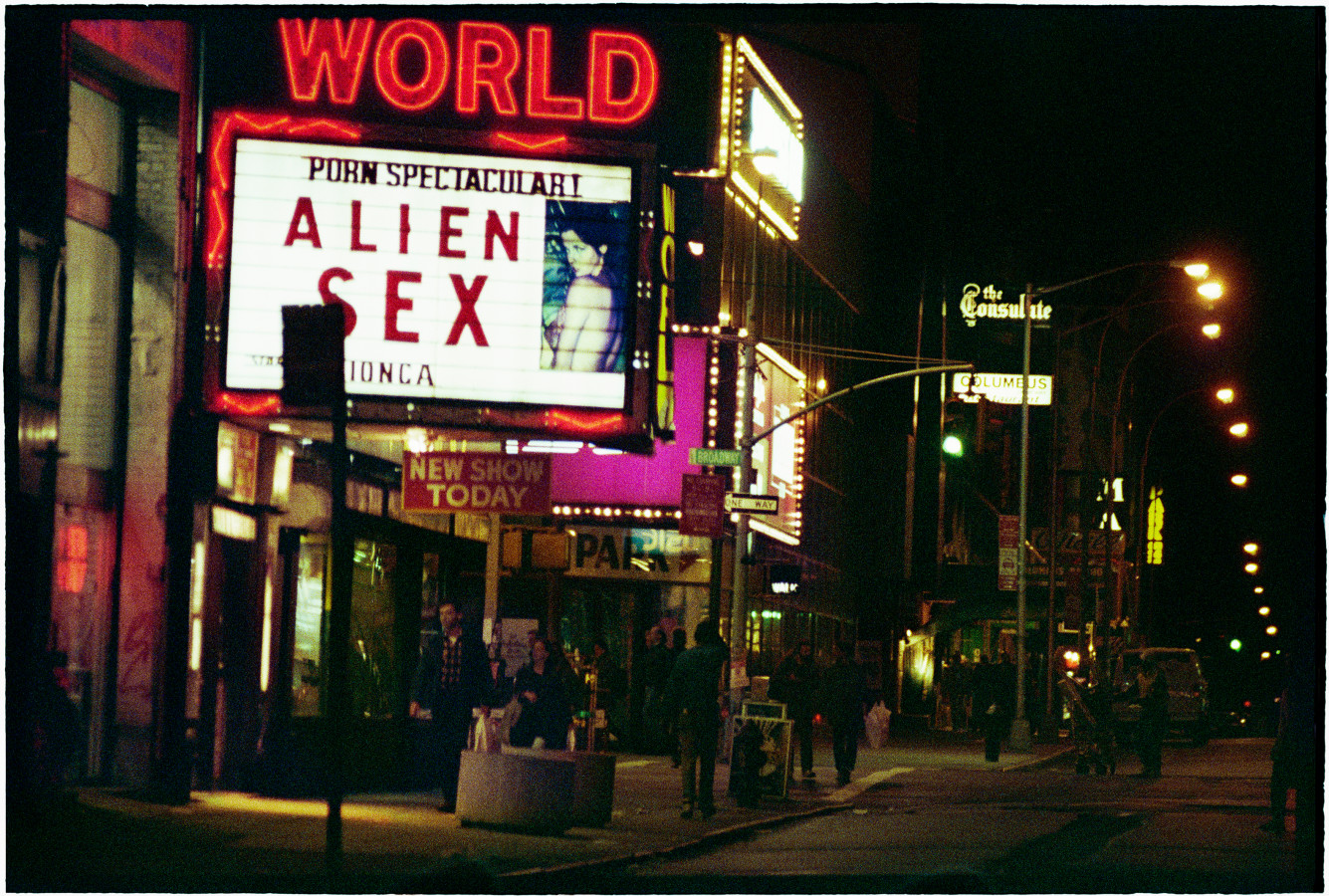

Dark, grainy and full of shadows Bill Henson’s latest show draws on 35 mm colour film shot in New York City in 1989.

Bill Henson is one of Australia’s best-known contemporary photographers. When a show by this calibre of artist opens here, the art world waits with bated breath to see what he will unveil.

This time, he presents a historically important landscape series that chronicles a time in New York City that no longer exists. It’s a nostalgic trip back in time, a nocturnal odyssey through the frenetic, neon-lit streets of a long-lost America.

Known for his chiaroscuro style, Henson’s cinematic photographs often transform his subject into ambiguous objects of beauty. This time round, the show presents a mysterious walk through the streets of Manhattan, evoking a seedy, yet beautiful vision of the city.

Relying on generative gaps, these landscapes result from Henson mining his archive of negatives and manipulating them to produce a finished print. Sometimes, they are composed by a principle of magnification, with Henson honing in on details, and sometimes, they are created through areas of black being expanded to make the scene more cinematic and foreboding. Like silence in a film or the pause in a pulse, the black suggests the things you can’t see.

Henson’s illustrious career has spanned four decades and was memorably marred by controversy over a series of nude adolescent photographs shown in 2008, which made him front-page news for weeks. This series of portraits made Henson the subject of a police investigation during which no offence was found.

In recent years, Henson has been a sharp critic of cancel culture, encouraging artists to contribute something that will have lasting value and add to the conversation, rather than tearing down the past.

His work deals with the liminal space between the mystical and the real, the seen and unseen, the boundary between youth and adulthood.

His famous Paris Opera Project, 1990-91, pictured above, is similarly intense as the current show, dwelling on the border between the painterly and the cinematic.

Bill Henson’s ‘The Liquid Night’ runs until 11 May 2024 at Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery.

Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, 8 Soudan Ln, Paddington NSW; roslynoxley9.com.au