Watches that are more like works of fine art

Watchmaking remains one of the last bastions for the preservation of exquisite handicrafts.

Related articles

Visiting the Russian town of Vyatka in 1837, Alexander Nikolaevich Romanov was seized by the urge to buy a pocket watch. The timepiece he coveted was expensive – nearly twice the cost of a watch cased in gold – though that did not concern the future tsar. What really caught his attention was that the watch was locally made, completely carved out of wood.

The maker was a man named Semyon Ivanovitch Bronnikov, a carpenter who taught himself horology while repairing wooden clock enclosures. He became a watchmaker by trial and error, cutting his gears by hand and fitting his wooden movements into cases of birch; only the springs, pivots and pinions were metal. He taught this métier to his sons, one of whom passed his knowledge on to his own son. By the early 20th century, when the last of the dynasty retired, the Bronnikovs had likely built some 500 timepieces.

Wooden watchmaking was a bona fide Vyatka tradition and the demise of the custom was a loss to Slavic cultural heritage. Nearly a century later, a young Ukrainian cabinetmaker became interested in horology while restoring the cases of old grandfather clocks. Like the Bronnikovs, Valerii Danevych had no metalworking skills – let alone horological training – so he started making clocks instinctually, crafting his own wooden gears with a saw. The Bronnikov watches, some of which are now in the State Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg, soon inspired him to try his hand at miniaturisation. He began creating pocket watches and wristwatches of increasing complexity, culminating in a dual retrograde wristwatch with flying tourbillon.

Danevych’s Retrograde took 1800 working hours to complete. Aside from several springs, all 188 parts (including pinions and pivots) are wood, a feat he achieved by taking advantage of the distinct physical characteristics of materials ranging from bamboo to ironwood. Some of these woods even surpass metal in certain respects, including self-lubrication. (Natural oils in woods were also exploited by John Harrison, an early carpenter-turned-watchmaker whose first record-breaking marine chronometer used oak cogs.) Revitalising the Bronnikov tradition, Danevych shares the richness of traditional crafts and also reminds us how easily they can be lost if not continuously practised.

The importance of old-world métiers d’art has been recognised by no less an institution than the United Nations, which has also acknowledged their precariousness: in recent years, UNESCO has broadened international protection of World Heritage Sites to encompass “intangible cultural heritage” ranging from Chinese calligraphy to Zmijanje embroidery. Yet the UN’s guardianship is fundamentally defensive. Cultural heritage needs to be practised and appreciated, and no institution or industry is more actively promoting and advancing historic métiersd’art than haute horlogerie.

In 1839, two years after Semyon Bronnikov sold his first pocket watch, Antoine Norbert de Patek and François Czapek started an horological partnership in Geneva. Patek, Czapek & Cie. specialised in decorating watch cases, a business that thrived since no watch was considered complete unless it was elaborately engraved. The craft required years of training and was notoriously unforgiving. An artisan had to control the tip of his burin with nothing more than the strength of his hands, confidently embellishing precious metal with arabesques and heraldry.

Exquisite workmanship established the new brand, which became Patek Philippe, a company renowned for combining fine watchmaking with choice artistry and for nurturing generations of craftsmen. Then tastes changed.

By the ’70s, nobody bought highly decorated watches and there was no longer a market for engravers. Faced by the prospect that artisans would seek other kinds of work and their skills would be lost, Patek continued to commission engraving, quietly putting unloved watches into storage.

It has taken just a few decades for Patek’s decision to be vindicated, and the talent of the brand’s engravers is now matched once more by the appreciation of collectors. The new Grandmaster Chime, released for the company’s 175th anniversary, is as lavishly ornamented as the most accomplished 19th-century creations. Every facet of the reversible rose-gold case is engraved, complementing the supremely complicated 1366-component movement and testifying to the vitality of case engraving as an art form.

Yet engraving was not the only traditional watchmaking métier threatened in the late 20th century, and Patek Philippe was not the only company to take responsibility for preserving the Swiss watchmaking heritage. Vacheron Constantin was also a crucial patron, sustaining the livelihood and savoir faire of artisans in disciplines like enamelling.

The value of what the brand preserved is evident in its latest collection of enamel-dialled watches, which feature the craft of miniature painting. The Métiers d’Art Savoirs Enluminés take inspiration from an art form that truly has gone extinct: the medieval art of manuscript illumination. Vacheron Constantin has selected three painted miniatures of mythical Celtic creatures from the 12th-century Aberdeen Bestiary, each faithfully reproduced on the upper level of a complicated gold watch dial.

The dials are created using the medieval technique of champlevé, in which gold is carved away and replaced by layers of enamel made of ground glass that fuses to the metal in a furnace. To emulate the rich hues of the original Aberdeen illumination, the enamels are coloured with metallic oxides. The delicate features of the animals are replicated by applying enamel with a fine brush in many translucent layers, with the dial fired after each application.

The enameller must know how the metal oxides will interact with one another and react to the heat of the fire, depending on years of experience and sometimes generations of expertise.

Without an industry to support the art form, individual artisans might not have the means to develop their craft and a millennium of accumulated knowledge could be forgotten. Such were the prospects in the ’70s. Yet through contemporary haute horlogerie– supported by the connoisseurship of collectors – métiers d’art associated with old-world watchmaking traditions are instead undergoing a renaissance.

Visiting the Ishikawa Prefecture of Japan in 2014, Philippe Delhotal heard about a painter so dexterous that he could inscribe a Buddhist prayer on a grain of rice. As the artistic director for La Montre Hermès, Delhotal was curious. He sought out 70-year-old Buzan Fukushima, a master of red painting on porcelain known as Aka-e, and inquired whether Fukushima would be willing to create two dozen Hermès watch faces by applying his traditional glazing technique to porcelain dials made in Sèvres.

The result was a first for both Aka-e and watchmaking. Depicting a legendary Japanese horse race delicately painted in shades of red and ochre with gold embellishment, the Slim d’Hermès Koma Kurabe brings to watchmaking a 19th-century métier d’art conventionally applied to vases, and brings to Aka-e a new source of patronage. From the standpoint of haute horlogerie, all cultural heritage is esteemed and every métier deserves consideration.

Maki-e – a type of lacquerwork in which powders of precious metal and pigment are embedded between layers of resin to create images in relief – has also recently begun to enhance and be enhanced by haut de gamme watchmaking. Originating in eighth-century Japan, the art form is treasured by the Japanese Imperial Household, which over the past century has commissioned some of the finest examples from the Yamada Heiando Studio.

Several years ago, Yamada Heiando began to make dials for Chopard L.U.C XP Urushi watches. The work is personally undertaken by Minori Koizumi, the studio’s master craftsman. To make his 2015 dial celebrating the Chinese Year of the Goat required dozens of applications of powder and lacquer, sequentially deposited and polished by hand over a full month. Each layer contributes depth, but Koizumi must also take care to avoid buildup that would obstruct the watch hands. To serve the needs of horology, the traditional technique has been adapted: as a métier d’art, Maki-e is both ancient and novel.

A similar renewal is taking place with gem carving, or glyptic, which dates back to ancient Mesopotamia, where insignia were cut into stone cylinders used as seals. In Greco-Roman times intaglio- and cameo-cut gems were set in jewellery, and by the Renaissance Italian artisans composed whole scenes in carved jaspers and agates.

Avid collectors of glyptic included Lorenzo de’ Medici and Catherine the Great. The craft has been neglected over the past 150 years, however, and few masters of glyptic persist.

In the Geneva-area municipality of Carouge, Chanel found one of them and commissioned him to make carved stone dials for its Mademoiselle Privé ladies’ watch collection, inspired by imagery of birds on Coco Chanel’s antique Coromandel screens. New tools had to be designed to manipulate the minuscule pieces of carnelian, turquoise and lapis, and the thinness of the dial required that the scenery be rendered in forced perspective. With Mademoiselle Privé, Chanel is not only helping to return glyptic to its former glory, but also inspiring glyptic artisans to be inventive.

In much the same way, micromosaic was once among the most coveted of arts, only to be nearly forgotten. Developed in 18th-century Rome, where they were known as eternal paintings, the diminutive mosaics decorated jewellery and vases. Like the ancient floor and wall mosaics that inspired them, micromosaics were crafted by fitting together thousands of tiny coloured glass pieces to make images or patterns. Unlike mosaic floors, some micromosaics used semiprecious stones. They reached their peak with Napoleon, who gave them to dignitaries he sought to impress, and now they are regaining their former prestige through the efforts of Cartier.

Over the past few years, the company has presented several watches with micromosaic dials. One of the most recent examples, depicting a white Royal Bengal tiger, incorporates irregularly shaped cacholong tesserae on a background of square-cut lapis lazuli, dumortierite and blue agate tiles. Each watch face includes more than 500 minuscule stones and each composition takes more than 60 hours of painstaking labour.

But time is even more significant in another sense. Like any métier d’art, micromosaic takes years to master. By continuously producing micromosaic dials and presenting new challenges, Cartier sustains the art form as artisans mature.

The term ‘métier d’art’evokes heritage. By nurturing and reviving traditional crafts, haute horlogerie ensures that heritage does not become history. However, sustaining ancient arts is not enough; haute horlogerie reaches its full potential when it also begins new traditions of craftsmanship by creating new métiers.

Recently, the future came courtesy of Harry Winston. With its Premier Precious Butterfly collection, the company invented a technique that may one day be as classic as micromosaic or Maki-e. Watch faces are coloured with iridescent powder dusted from the wings of butterflies, making the powder fundamentally unlike the pigments used in paints, glazes, enamels and lacquers. Pigments take their colour by absorbing a specific wavelength of light, but because the colouration of butterflies is structural, light waves are selectively refracted and reflected. With the Premier Precious Butterfly collection, Harry Winston put this vivid effect in the hands of artisans.

And that is where all great métiers d’art begin. Just consider the creative handiwork of Semyon Ivanovitch Bronnikov.

Subscribe to the Newsletter

Recommended for you

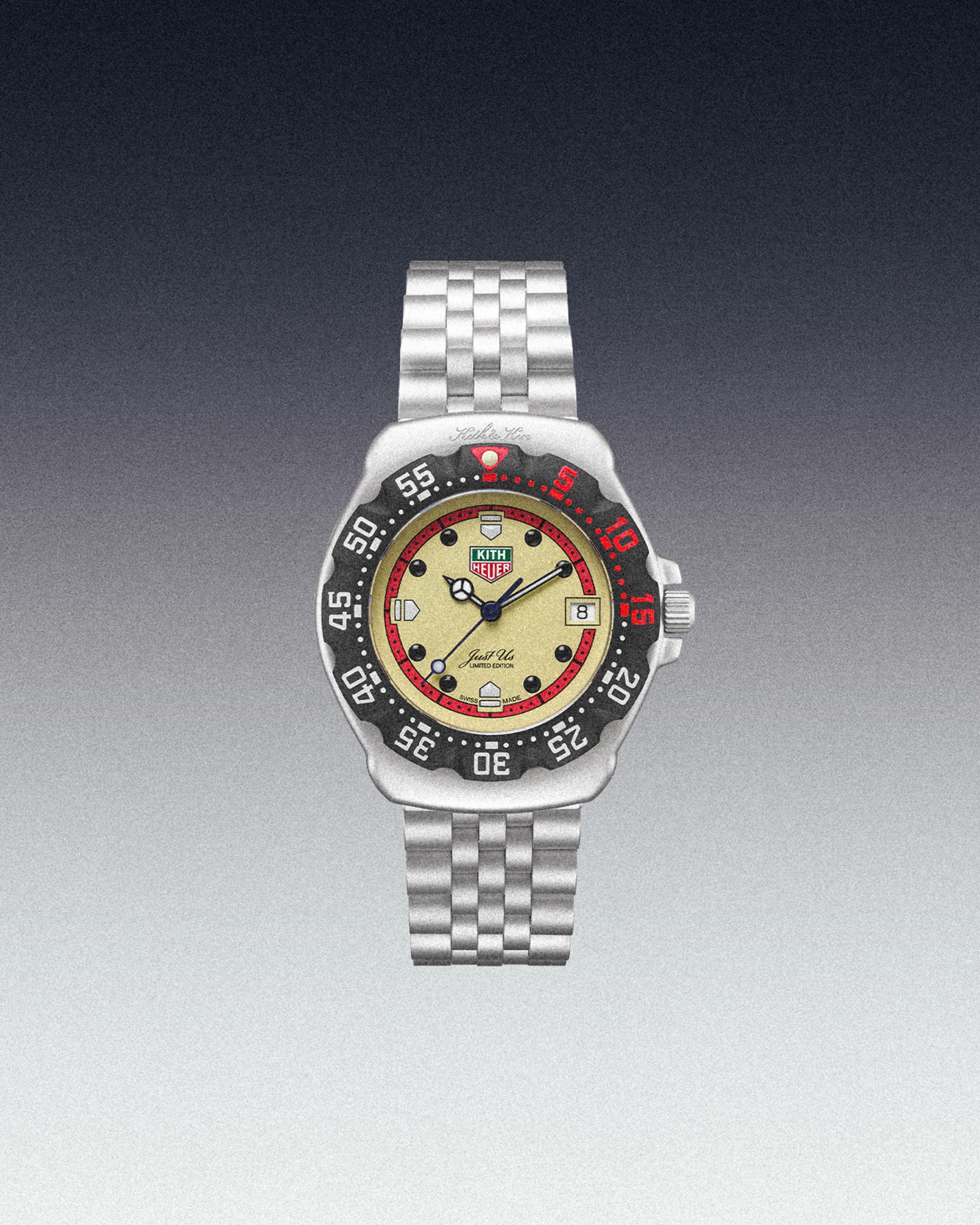

Watch of the Week: TAG Heuer Formula 1 | Kith

The legendary sports watch returns, but with an unexpected twist.

By Josh Bozin

May 2, 2024

Omega Reveals a New Speedmaster Ahead of the Paris 2024 Olympics

Your first look at the new Speedmaster Chronoscope, designed in the colour theme of the Paris Olympics.

By Josh Bozin

April 26, 2024

You may also like.

You may also like.

Watch of the Week: TAG Heuer Formula 1 | Kith

The legendary sports watch returns, but with an unexpected twist.

Over the last few years, watch pundits have predicted the return of the eccentric TAG Heuer Formula 1, in some shape or form. It was all but confirmed when TAG Heuer’s heritage director, Nicholas Biebuyck, teased a slew of vintage models on his Instagram account in the aftermath of last year’s Watches & Wonders 2023 in Geneva. And when speaking with Frédéric Arnault at last year’s trade fair, the former CEO asked me directly if the brand were to relaunch its legacy Formula 1 collection, loved by collectors globally, how should they go about it?

My answer to the baited entreaty definitely didn’t mention a collaboration with Ronnie Fieg of Kith, one of the world’s biggest streetwear fashion labels. Still, here we are: the TAG Heuer Formula 1 is officially back and as colourful as ever.

As the watch industry enters its hype era—in recent years, we’ve seen MoonSwatches, Scuba Fifty Fathoms, and John Mayer G-Shocks—the new Formula 1 x Kith collaboration might be the coolest yet.

Here’s the lowdown: overnight, TAG Heuer, together with Kith, took to socials to unveil a special, limited-edition collection of Formula 1 timepieces, inspired by the original collection from the 1980s. There are 10 new watches, all limited, with some designed on a stainless steel bracelet and some on an upgraded rubber strap; both options nod to the originals.

Seven are exclusive to Kith and its global stores (New York, Los Angeles, Miami, Hawaii, Tokyo, Toronto, and Paris, to be specific), and are made in an abundance of colours. Two are exclusive to TAG Heuer; and one is “shared” between TAG Heuer and Kith—this is a highlight of the collection, in our opinion. A faithful play on the original composite quartz watch from 1986, this model, limited to just 1,350 pieces globally, features the classic black bezel with red accents, a stainless steel bracelet, and that creamy eggshell dial, in all of its vintage-inspired glory. There’s no doubt that this particular model will present as pure nostalgia for those old enough to remember when the original TAG Heuer Formula 1 made its debut.

Of course, throughout the collection, Fieg’s design cues are punctuated: the “TAG” is replaced with “Kith,” forming a contentious new brand name for this specific release, as well as Kith’s slogan, “Just Us.”

Collectors and purists alike will appreciate the dedication to the original Formula 1 collection: features like the 35mm Arnite cases—sourced from the original 80s-era supplier—the form hour hand, a triangle with a dot inside at 12 o’clock, indices that alternate every quarter between shields and dots, and a contrasting minuterie, are all welcomed design specs that make this collaboration so great.

Every TAG Heuer Formula 1 | Kith timepiece will be presented in an eye-catching box that complements the fun and colour theme of Formula 1 but drives home the premium status of this collaboration. On that note, at $2,200 a piece, this isn’t exactly an approachable quartz watch but reflects the exclusive nature of Fieg’s Kith brand and the pieces he designs (largely limited-edition).

So, what do we think? It’s important not to understate the significance of the arrival of the TAG Heuer Formula 1 in 1986, in what would prove integral in setting up the brand for success throughout the 90’s—it was the very first watch collection to have “TAG Heuer” branding, after all—but also in helping to establish a new generation of watch consumer. Like Fieg, many millennial enthusiasts will recall their sentimental ties with the Formula 1, often their first timepiece in their horological journey.

This is as faithful of a reissue as we’ll get from TAG Heuer right now, and budding watch fans should be pleased with the result. To TAG Heuer’s credit, a great deal of research has gone into perfecting and replicating this iconic collection’s proportions, materials, and aesthetic for the modern-day consumer. Sure, it would have been nice to see a full lume dial, a distinguishing feature on some of the original pieces—why this wasn’t done is lost on me—and perhaps a more approachable price point, but there’s no doubt these will become an instant hit in the days to come.

—

The TAG Heuer Formula 1 | Kith collection will be available on Friday, May 3rd, exclusively in-store at select TAG Heuer and Kith locations in Miami, and available starting Monday, May 6th, at select TAG Heuer boutiques, all Kith shops, and online at Kith.com. To see the full collection, visit tagheuer.com

You may also like.

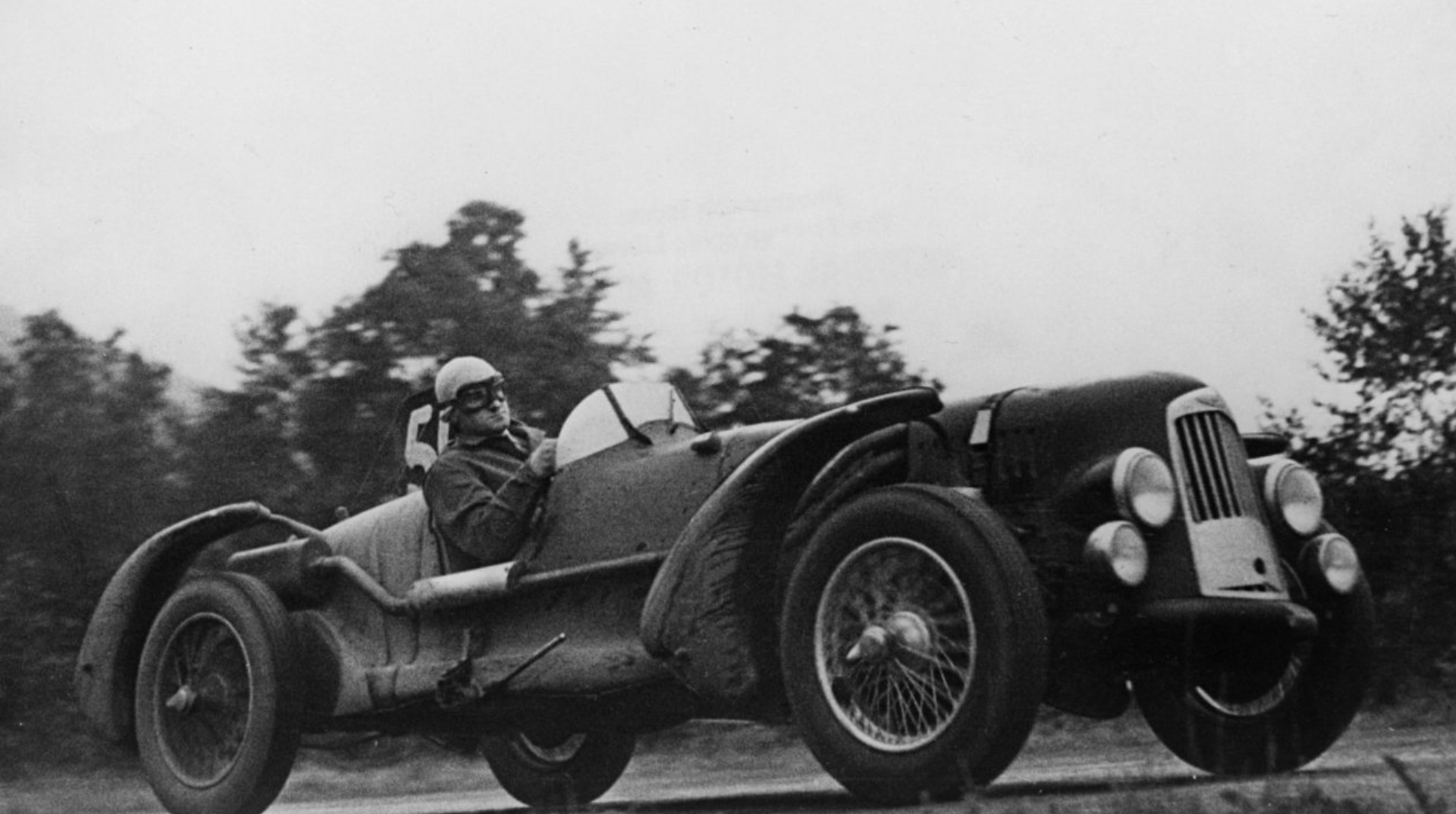

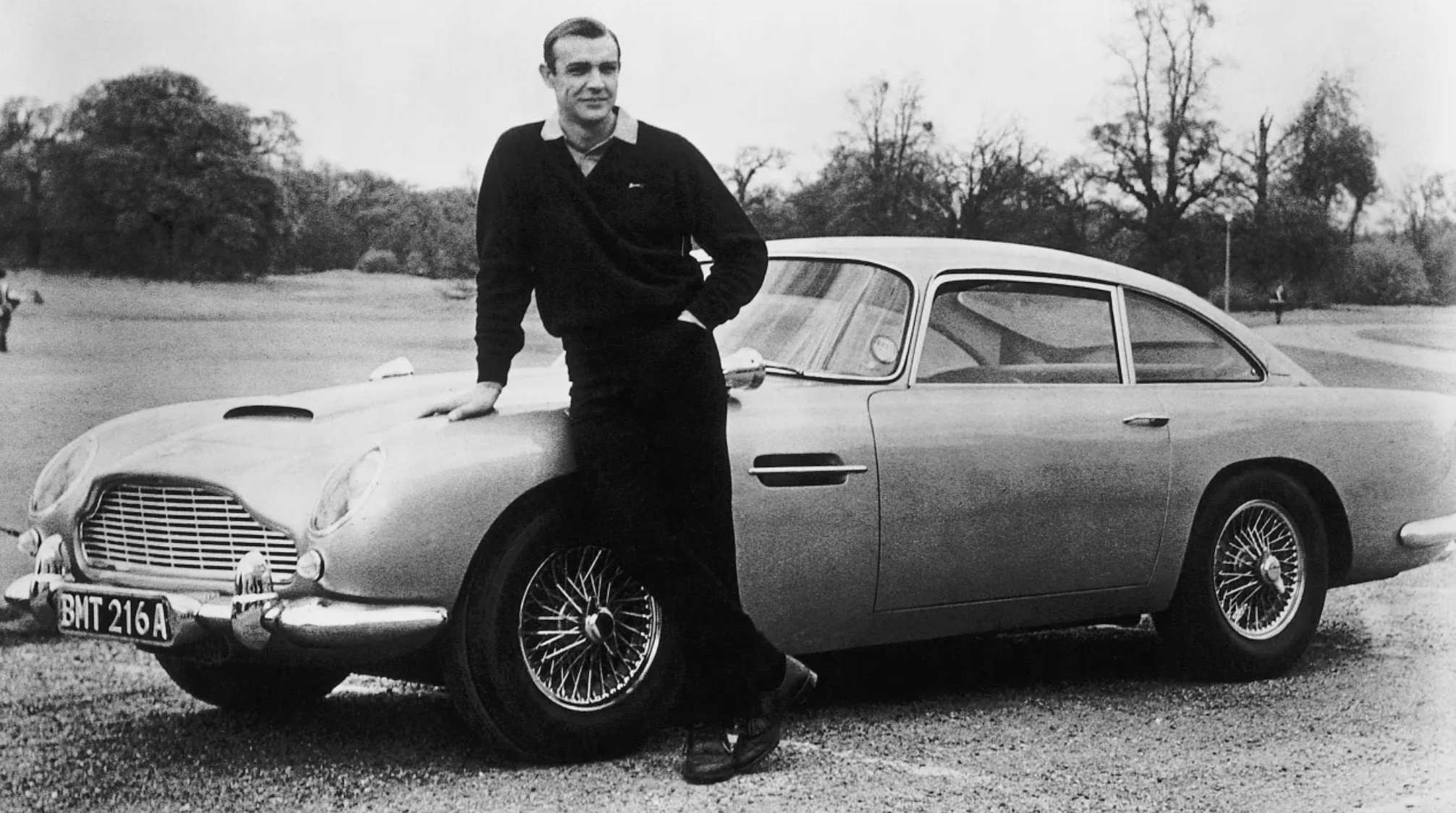

8 Fascinating Facts You Didn’t Know About Aston Martin

The British sports car company is most famous as the vehicle of choice for James Bond, but Aston Martin has an interesting history beyond 007.

Aston Martin will forever be associated with James Bond, ever since everyone’s favourite spy took delivery of his signature silver DB5 in the 1964 film Goldfinger. But there’s a lot more to the history of this famed British sports car brand beyond its association with the fictional British Secret Service agent.

Let’s dive into the long and colourful history of Aston Martin.

You may also like.

What Venice’s New Tourist Tax Means for Your Next Trip

The Italian city will now charge visitors an entry fee during peak season.

Visiting the Floating City just got a bit more expensive.

Venice is officially the first metropolis in the world to start implementing a day-trip fee in an effort to help the Italian hot spot combat overtourism during peak season, The Associated Press reported. The new program, which went into effect, requires travellers to cough up roughly €5 (about $AUD8.50) per person before they can explore the city’s canals and historic sites. Back in January, Venice also announced that starting in June, it would cap the size of tourist groups to 25 people and prohibit loudspeakers in the city centre and the islands of Murano, Burano, and Torcello.

“We need to find a new balance between the tourists and residents,’ Simone Venturini, the city’s top tourism official, told AP News. “We need to safeguard the spaces of the residents, of course, and we need to discourage the arrival of day-trippers on some particular days.”

During this trial phase, the fee only applies to the 29 days deemed the busiest—between April 25 and July 14—and tickets will remain valid from 8:30 am to 4 pm. Visitors under 14 years of age will be allowed in free of charge in addition to guests with hotel reservations. However, the latter must apply online beforehand to request an exemption. Day-trippers can also pre-pay for tickets online via the city’s official tourism site or snap them up in person at the Santa Lucia train station.

“With courage and great humility, we are introducing this system because we want to give a future to Venice and leave this heritage of humanity to future generations,” Venice Mayor Luigi Brugnaro said in a statement on X (formerly known as Twitter) regarding the city’s much-talked-about entry fee.

Despite the mayor’s backing, it’s apparent that residents weren’t totally pleased with the program. The regulation led to protests and riots outside of the train station, The Independent reported. “We are against this measure because it will do nothing to stop overtourism,” resident Cristina Romieri told the outlet. “Moreover, it is such a complex regulation with so many exceptions that it will also be difficult to enforce it.”

While Venice is the first city to carry out the new day-tripper fee, several other European locales have introduced or raised tourist taxes to fend off large crowds and boost the local economy. Most recently, Barcelona increased its city-wide tourist tax. Similarly, you’ll have to pay an extra “climate crisis resilience” tax if you plan on visiting Greece that will fund the country’s disaster recovery projects.

You may also like.

Omega Reveals a New Speedmaster Ahead of the Paris 2024 Olympics

Your first look at the new Speedmaster Chronoscope, designed in the colour theme of the Paris Olympics.

The starters are on the blocks, and with less than 100 days to go until the Paris 2024 Olympics, luxury Swiss watchmaker Omega was bound to release something spectacular to mark its bragging rights as the official timekeeper for the Summer Games. Enter the new 43mm Speedmaster Chronoscope, available in new colourways—gold, black, and white—in line with the colour theme of the Olympic Games in Paris this July.

So, what do we get in this nicely-wrapped, Olympics-inspired package? Technically, there are four new podium-worthy iterations of the iconic Speedmaster.

The new versions present handsomely in stainless steel or 18K Moonshine Gold—the brand’s proprietary yellow gold known for its enduring shine. The steel version has an anodised aluminium bezel and a stainless steel bracelet or vintage-inspired perforated leather strap. The Moonshine Gold iteration boasts a ceramic bezel; it will most likely appease Speedy collectors, particularly those with an affinity for Omega’s long-standing role as stewards of the Olympic Games.

Notably, each watch bears an attractive white opaline dial; the background to three dark grey timing scales in a 1940s “snail” design. Of course, this Speedmaster Chronoscope is special in its own right. For the most part, the overall look of the Speedmaster has remained true to its 1957 origins. This Speedmaster, however, adopts Omega’s Chronoscope design from 2021, including the storied tachymeter scale, along with a telemeter, and pulsometer scale—essentially, three different measurements on the wrist.

While the technical nature of this timepiece won’t interest some, others will revel in its theatrics. Turn over each timepiece, and instead of a transparent crystal caseback, there is a stamped medallion featuring a mirror-polished Paris 2024 logo, along with “Paris 2024” and the Olympic Rings—a subtle nod to this year’s games.

Powering this Olympiad offering—and ensuring the greatest level of accuracy—is the Co-Axial Master Chronometer Calibre 9908 and 9909, certified by METAS.

A Speedmaster to commemorate the Olympic Games was as sure a bet as Mondo Deplantis winning gold in the men’s pole vault—especially after Omega revealed its Olympic-edition Seamaster Diver 300m “Paris 2024” last year—but they delivered a great addition to the legacy collection, without gimmickry.

However, the all-gold Speedmaster is 85K at the top end of the scale, which is a lot of money for a watch of this stature. By comparison, the immaculate Speedmaster Moonshine gold with a sun-brushed green PVD “step” dial is 15K cheaper, albeit without the Chronoscope complications.

—

The Omega Speedmaster Chronoscope in stainless steel with a leather strap is priced at $15,725; stainless steel with steel bracelet at $16,275; 18k Moonshine Gold on leather strap $54,325; and 18k Moonshine Gold with matching gold bracelet $85,350, available at Omega boutiques now.

Discover the collection here

You may also like.

Here’s What Goes Into Making Jay-Z’s $1,800 Champagne

We put Armand de Brignac Blanc de Noirs Assemblage No. 4 under the microsope.

In our quest to locate the most exclusive and exciting wines for our readers, we usually ask the question, “How many bottles of this were made?” Often, we get a general response based on an annual average, although many Champagne houses simply respond, “We do not wish to communicate our quantities.” As far as we’re concerned, that’s pretty much like pleading the Fifth on the witness stand; yes, you’re not incriminating yourself, but anyone paying attention knows you’re probably guilty of something. In the case of some Champagne houses, that something is making a whole lot of bottles—millions of them—while creating an illusion of rarity.

We received the exact opposite reply regarding Armand de Brignac Blanc de Noirs Assemblage No. 4. Yasmin Allen, the company’s president and CEO, told us only 7,328 bottles would be released of this Pinot Noir offering. It’s good to know that with a sticker price of around $1,800, it’s highly limited, but it still makes one wonder what’s so exceptional about it.

Known by its nickname, Ace of Spades, for its distinctive and decorative metallic packaging, Armand de Brignac is owned by Louis Vuitton Moët Hennessy and Jay-Z and is produced by Champagne Cattier. Each bottle of Assemblage No. 4 is numbered; a small plate on the back reads “Assemblage Four, [X,XXX]/7,328, Disgorged: 20 April, 2023.” Prior to disgorgement, it spent seven years in the bottle on lees after primary fermentation mostly in stainless steel with a small amount in concrete. That’s the longest of the house’s Champagnes spent on the lees, but Allen says the winemaking team tasted along the way and would have disgorged earlier than planned if they’d felt the time was right.

Chef de cave, Alexandre Cattier, says the wine is sourced from some of the best Premier and Grand Cru Pinot Noir–producing villages in the Champagne region, including Chigny-les-Roses, Verzenay, Rilly-la-Montagne, Verzy, Ludes, Mailly-Champagne, and Ville-sur-Arce in the Aube département. This is considered a multi-vintage expression, using wine from a consecutive trio of vintages—2013, 2014, and 2015—to create an “intense and rich” blend. Seventy percent of the offering is from 2015 (hailed as one of the finest vintages in recent memory), with 15 percent each from the other two years.

This precisely crafted Champagne uses only the tête de cuvée juice, a highly selective extraction process. As Allen points out, “the winemakers solely take the first and freshest portion of the gentle cuvée grape press,” which assures that the finished wine will be the highest quality. Armand de Brignac used grapes from various sites and three different vintages so the final product would reflect the house signature style. This is the fourth release in a series that began with Assemblage No. 1. “Testing different levels of intensity of aromas with the balance of red and dark fruits has been a guiding principle between the Blanc de Noirs that followed,” Allen explains.

The CEO recommends allowing the Assemblage No. 4 to linger in your glass for a while, telling us, “Your palette will go on a journey, evolving from one incredible aroma to the next as the wine warms in your glass where it will open up to an extraordinary length.” We found it to have a gorgeous bouquet of raspberry and Mission fig with hints of river rock; as it opened, notes of toasted almond and just-baked brioche became noticeable. With striking acidity and a vein of minerality, it has luscious nectarine, passion fruit, candied orange peel, and red plum flavors with touches of beeswax and a whiff of baking spices on the enduring finish. We enjoyed our bottle with a roast chicken rubbed with butter and herbes de Provence and savored the final, extremely rare sip with a bit of Stilton. Unfortunately, the pairing possibilities are not infinite with this release; there are only 7,327 more ways to enjoy yours.