The never-ending battle for ultra-thin supremacy

Mastery of ultra-thin horology is a particular source of pride for watchmakers.

Related articles

Mastery of ultra-thin horology is a particular source of pride for the watchmakers of Bulgari, which earlier this year introduced the world’s thinnest self-winding wristwatch, the Octo Finissimo Automatic.

“For us, Finissimo is really a statement,” says Fabrizio Buonamassa-Stigliani, the company’s lead watch designer. “Each is sort of a grand complication. It is the technical flagship of the brand.”

Bulgari’s recent world records — which also include thinnest wristwatch tourbillon and minute repeate — result from genuine technical achievements backed by impressive design. Yet the skillfulness and competitive spirit driving the company’s efforts are the same dynamics that have guided the creation of ultrathin pieces throughout watchmaking’s history.

Thinness and compactness have served as indicators of a watch’s technical sophistication for well over two centuries, especially after Abraham-Louis Breguet began to emphasise those qualities in his pieces at the beginning of the 19th century. Then, as now, the challenge lay in crafting components of the thinnest practical dimensions and then carefully assembling them to function properly. Aligning the wheels and ensuring the proper pressures and clearances are exponentially more difficult tasks in specialised ultra – thin movements — so much so that the work is usually performed by high-level watchmakers with expertise in complications.

“A normal [mainspring] barrel and ratchet can be adjusted in half an hour to one hour,” says John Sheridan, a master watchmaker at Bulgari’s Le Sentier manufacture. “The same mechanism on ultra-thin watches takes a day. Too much pressure can constrict the spring, and you can lose 30 degrees of amplitude in the balance just like that.”

Difficulties also increase as pieces get more complicated. The extra-thin minute repeater the brand unveiled last year takes just as long to build as a grande sonnerie, the most complex model in Bulgari’s portfolio. Of course, much depends on the quality of the parts, which are produced today by computer-numerical-control (CNC) machines that must be specially programmed and handled for such precise milling.

“It’s the same machines for producing an ultra-thin movement and regular movements,” notes Sheridan, “but the time for machining the parts is two to three times than for regular parts because the precision requirements are higher. Much of this is in the setup of the machine.”

The emphasis on handwork and adjustment in watchmaking was much more pronounced a century ago, when skilled artisans produced ultra-thin watches that might embarrass today’s top practitioners.

In 1907 — more than a quarter-century before their names would be united under a single marque — the Swiss movement maker LeCoultre produced a calibre that was an amazing 1.38 millimetres thick for French watchmaker Edmond Jaeger. Caliber 145 was produced in small numbers and just for pocket watches. Its flabbergastingly svelte dimensions (the thin – nest contemporary wrist – watch movements are 25 percent thicker) were facilitated by the large diameter of the pocket-watch movement and, to an even greater degree, the manufacturing methods of the day, which allowed skilled watchmakers to play with nearly every facet of component fabrication and assembly on an individual basis.

It was the small watch and component maker Piaget, however, that first discovered it could distinguish itself by becoming a modern specialist in ultra-thin watchmaking. Piaget’s introduction of the 2-millimetre-thick 9P manual movement in 1957 and the only slightly thicker 12P automatic movement 3 years later gave rise to a whole generation of remarkably elegant wristwatches that seemed to indelibly tie the brand to ultra-slim horology.

Piaget’s 12P incorporated the recently developed micro rotor, which wound the watch by way of a small mass recessed into the movement. Suspended by two bridges, the device fit the diminutive dimensions of the movement impeccably, and the component is often used in ultra-thin watchmaking to this day. Panache, however, was not necessarily a priority for Piaget’s designers, who deliberately favoured conventional movement architecture — an approach the company has adhered to with the new-generation ultra-thin calibres it has introduced at intervals since the late 1990s.

“The more simple and basic you are in terms of architecture on the ultra–thins, the more reliable you are,” explains Quentin Hebert, one of Piaget’s movement specialists. “That is the chief design consideration for the whole 1200 family. There are no crazy constructions. What we do have to master is the repetition of the thinness of the components from one movement to another.”

As a result, the movements for Piaget’s relaunched Altiplano models back away slightly from the extreme dimensions of the 9P and 12P in favor of improved reliability and better flexing tolerance. Despite these concessions, the brand continues to see the value in producing record-setting thin watches. Subsequent versions of the 1200 (automatic) movement have established thinness records for automatic winding, subsidiary-seconds, skeleton, and diamond-set wristwatches.

According to the company, Piaget’s efforts in ultra-thin watchmaking are driven by considerations of aesthetics and style. However, it is difficult to believe that setting a world record was not one of the primary considerations behind the radical design of 2014’s Altiplano 900P. By using the caseback as the main plate of the movement, Piaget reduced the overall thickness of the watch to just 3.65 millimetres. The brand’s engineers are also quick to point out that the architecture permitted the use of full bridging on the movement, a construction Piaget has retained for function and reliability.

Although Piaget has consistently shown an essential conservatism in movement design, Bulgari — the new lead player in the segment — will not submit to such rigid constraints. One of the two ultra-thin models it launched in 2014 was a 1.95-millimetre thick tourbillon that dispensed with traditional bridging in favour of bearing systems to support several of the wheels in the gear train as well as the tourbillon cage. This arrangement might make conservative-minded watchmakers blanch, but Bulgari shaved nearly a millimetre off the movement height of its closest competitor.

“The bearings almost need to be individually polished for perfect running,” says Sheridan, who works on these movements almost daily at the Le Sentier facility. “Each has to be adjusted so that there is no movement or play in the bearing race, yet it runs freely. It’s a very delicate adjustment.”

Alongside the 2014 tourbillon, Bulgari released a hand-wound, small-seconds model that certainly qualified as ultrathin at 5.37 mm, though it broke no records. The design of the 2.353-millimetre-thick movement, however, demonstrates the company’s ambitious planning. This year, the movement was adjusted by removing the reverse-side power-reserve indicator and replacing it with a microrotor winding mechanism.

This configuration allowed the movement to be a few hundredths of a millimetre thinner than Piaget’s 12P and the watch to present a slimmer profile than Piaget’s thinnest automatic. The margins of difference in measurement may be tiny, but insofar as they serve to demonstrate the competency of the brand’s Le Sentier facility — now managed by Jean-Yves Basin — they are hugely significant.

For every record achieved by the makers of ultrathin watches, there are many stories of movements that were never brought to market or were discarded altogether because of functionality or reliability problems. Despite this failure rate, the quest for thinness is more relevant now than ever before. As increasing numbers of collectors prefer pieces — even complicated ones — that are wearable under the cuff, the competition to save space inside the case is yielding watches that are more enjoyable and comfortable to wear on the wrist day after day.

Subscribe to the Newsletter

Recommended for you

Watch of the Week: TAG Heuer Formula 1 | Kith

The legendary sports watch returns, but with an unexpected twist.

By Josh Bozin

May 2, 2024

Omega Reveals a New Speedmaster Ahead of the Paris 2024 Olympics

Your first look at the new Speedmaster Chronoscope, designed in the colour theme of the Paris Olympics.

By Josh Bozin

April 26, 2024

You may also like.

You may also like.

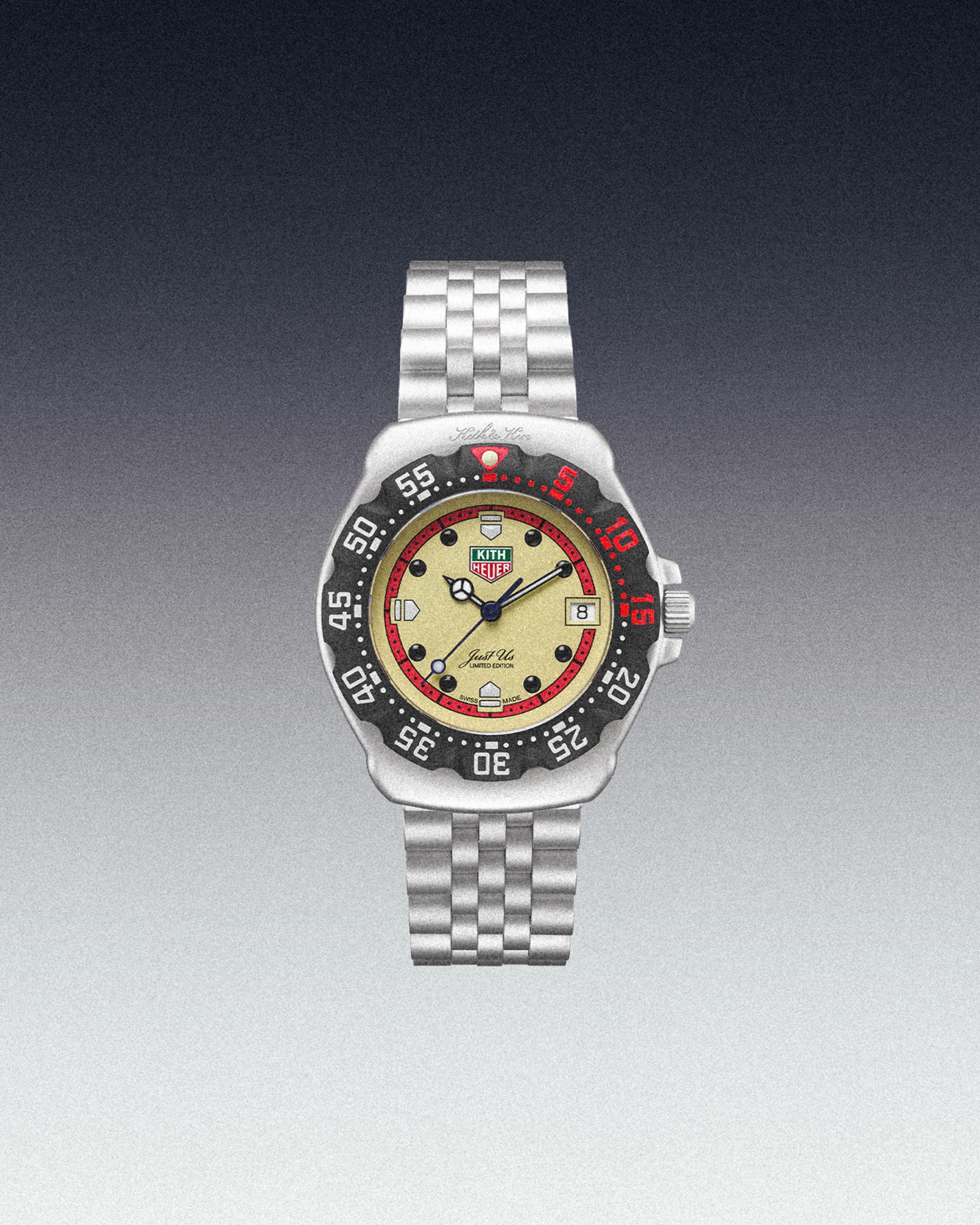

Watch of the Week: TAG Heuer Formula 1 | Kith

The legendary sports watch returns, but with an unexpected twist.

Over the last few years, watch pundits have predicted the return of the eccentric TAG Heuer Formula 1, in some shape or form. It was all but confirmed when TAG Heuer’s heritage director, Nicholas Biebuyck, teased a slew of vintage models on his Instagram account in the aftermath of last year’s Watches & Wonders 2023 in Geneva. And when speaking with Frédéric Arnault at last year’s trade fair, the former CEO asked me directly if the brand were to relaunch its legacy Formula 1 collection, loved by collectors globally, how should they go about it?

My answer to the baited entreaty definitely didn’t mention a collaboration with Ronnie Fieg of Kith, one of the world’s biggest streetwear fashion labels. Still, here we are: the TAG Heuer Formula 1 is officially back and as colourful as ever.

As the watch industry enters its hype era—in recent years, we’ve seen MoonSwatches, Scuba Fifty Fathoms, and John Mayer G-Shocks—the new Formula 1 x Kith collaboration might be the coolest yet.

Here’s the lowdown: overnight, TAG Heuer, together with Kith, took to socials to unveil a special, limited-edition collection of Formula 1 timepieces, inspired by the original collection from the 1980s. There are 10 new watches, all limited, with some designed on a stainless steel bracelet and some on an upgraded rubber strap; both options nod to the originals.

Seven are exclusive to Kith and its global stores (New York, Los Angeles, Miami, Hawaii, Tokyo, Toronto, and Paris, to be specific), and are made in an abundance of colours. Two are exclusive to TAG Heuer; and one is “shared” between TAG Heuer and Kith—this is a highlight of the collection, in our opinion. A faithful play on the original composite quartz watch from 1986, this model, limited to just 1,350 pieces globally, features the classic black bezel with red accents and a creamy-taupe, vintage-inspired dial. This particular model arrives on a steel bracelet with an eggshell dial and presents as pure nostalgia for those old enough to remember when the original TAG Heuer Formula 1 made its debut.

Of course, throughout the collection, Fieg’s design cues are punctuated: the “TAG” is replaced with “Kith,” forming a contentious new brand name for this specific release, as well as Kith’s slogan, “Just Us.”

Collectors and purists alike will appreciate the dedication to the original Formula 1 collection: features like the 35mm Arnite cases—sourced from the original 80s-era supplier—the form hour hand, a triangle with a dot inside at 12 o’clock, indices that alternate every quarter between shields and dots, and a contrasting minuterie, are all welcomed design specs that make this collaboration so great.

Every TAG Heuer Formula 1 | Kith timepiece will be presented in an eye-catching box that complements the fun and colour theme of Formula 1 but drives home the premium status of this collaboration. On that note, at $2,200 a piece, this isn’t exactly an approachable quartz watch but reflects the exclusive nature of Fieg’s Kith brand and the pieces he designs (largely limited-edition).

So, what do we think? It’s important not to understate the significance of the arrival of the TAG Heuer Formula 1 in 1986, in what would prove integral in setting up the brand for success throughout the 90’s—it was the very first watch collection to have “TAG Heuer” branding, after all—but also in helping to establish a new generation of watch consumer. Like Fieg, many millennial enthusiasts will recall their sentimental ties with the Formula 1, often their first timepiece in their horological journey.

This is as faithful of a reissue as we’ll get from TAG Heuer right now, and budding watch fans should be pleased with the result. To TAG Heuer’s credit, a great deal of research has gone into perfecting and replicating this iconic collection’s proportions, materials, and aesthetic for the modern-day consumer. Sure, it would have been nice to see a full lume dial, a distinguishing feature on some of the original pieces—why this wasn’t done is lost on me—and perhaps a more approachable price point, but there’s no doubt these will become an instant hit in the days to come.

—

The TAG Heuer Formula 1 | Kith collection will be available on Friday, May 3rd, exclusively in-store at select TAG Heuer and Kith locations in Miami, and available starting Monday, May 6th, at select TAG Heuer boutiques, all Kith shops, and online at Kith.com. To see the full collection, visit tagheuer.com

You may also like.

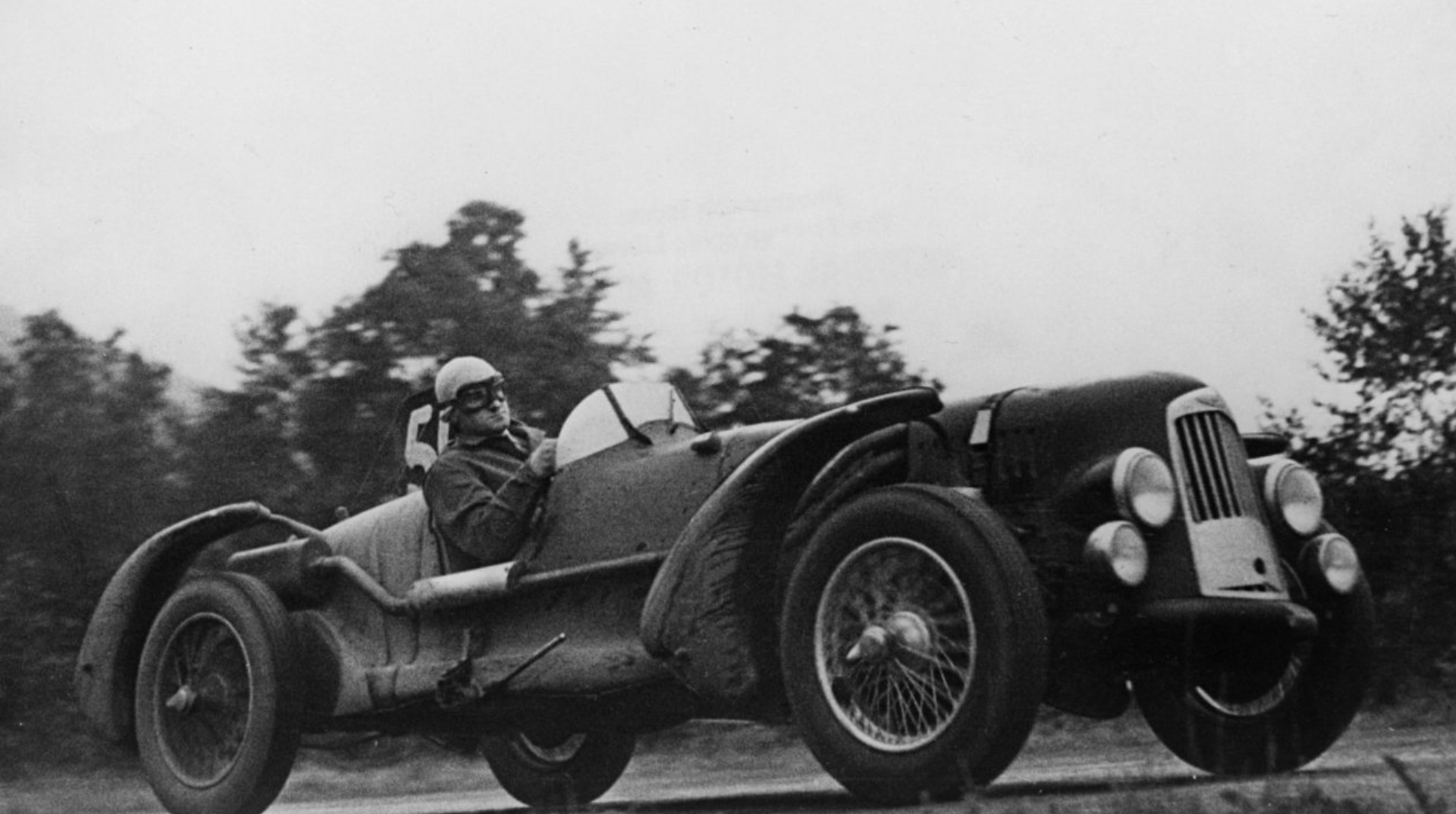

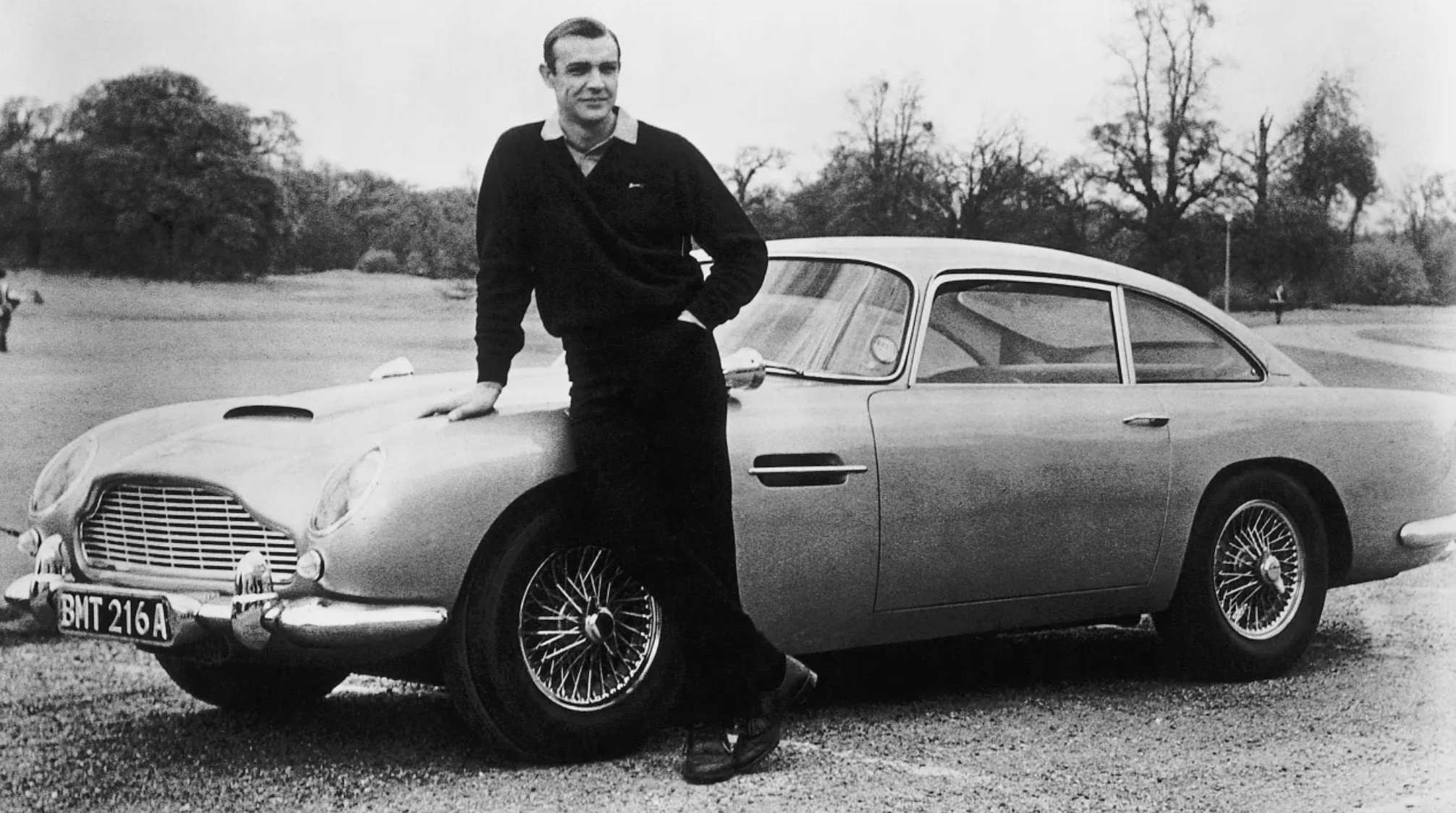

8 Fascinating Facts You Didn’t Know About Aston Martin

The British sports car company is most famous as the vehicle of choice for James Bond, but Aston Martin has an interesting history beyond 007.

Aston Martin will forever be associated with James Bond, ever since everyone’s favourite spy took delivery of his signature silver DB5 in the 1964 film Goldfinger. But there’s a lot more to the history of this famed British sports car brand beyond its association with the fictional British Secret Service agent.

Let’s dive into the long and colourful history of Aston Martin.

You may also like.

What Venice’s New Tourist Tax Means for Your Next Trip

The Italian city will now charge visitors an entry fee during peak season.

Visiting the Floating City just got a bit more expensive.

Venice is officially the first metropolis in the world to start implementing a day-trip fee in an effort to help the Italian hot spot combat overtourism during peak season, The Associated Press reported. The new program, which went into effect, requires travellers to cough up roughly €5 (about $AUD8.50) per person before they can explore the city’s canals and historic sites. Back in January, Venice also announced that starting in June, it would cap the size of tourist groups to 25 people and prohibit loudspeakers in the city centre and the islands of Murano, Burano, and Torcello.

“We need to find a new balance between the tourists and residents,’ Simone Venturini, the city’s top tourism official, told AP News. “We need to safeguard the spaces of the residents, of course, and we need to discourage the arrival of day-trippers on some particular days.”

During this trial phase, the fee only applies to the 29 days deemed the busiest—between April 25 and July 14—and tickets will remain valid from 8:30 am to 4 pm. Visitors under 14 years of age will be allowed in free of charge in addition to guests with hotel reservations. However, the latter must apply online beforehand to request an exemption. Day-trippers can also pre-pay for tickets online via the city’s official tourism site or snap them up in person at the Santa Lucia train station.

“With courage and great humility, we are introducing this system because we want to give a future to Venice and leave this heritage of humanity to future generations,” Venice Mayor Luigi Brugnaro said in a statement on X (formerly known as Twitter) regarding the city’s much-talked-about entry fee.

Despite the mayor’s backing, it’s apparent that residents weren’t totally pleased with the program. The regulation led to protests and riots outside of the train station, The Independent reported. “We are against this measure because it will do nothing to stop overtourism,” resident Cristina Romieri told the outlet. “Moreover, it is such a complex regulation with so many exceptions that it will also be difficult to enforce it.”

While Venice is the first city to carry out the new day-tripper fee, several other European locales have introduced or raised tourist taxes to fend off large crowds and boost the local economy. Most recently, Barcelona increased its city-wide tourist tax. Similarly, you’ll have to pay an extra “climate crisis resilience” tax if you plan on visiting Greece that will fund the country’s disaster recovery projects.

You may also like.

Omega Reveals a New Speedmaster Ahead of the Paris 2024 Olympics

Your first look at the new Speedmaster Chronoscope, designed in the colour theme of the Paris Olympics.

The starters are on the blocks, and with less than 100 days to go until the Paris 2024 Olympics, luxury Swiss watchmaker Omega was bound to release something spectacular to mark its bragging rights as the official timekeeper for the Summer Games. Enter the new 43mm Speedmaster Chronoscope, available in new colourways—gold, black, and white—in line with the colour theme of the Olympic Games in Paris this July.

So, what do we get in this nicely-wrapped, Olympics-inspired package? Technically, there are four new podium-worthy iterations of the iconic Speedmaster.

The new versions present handsomely in stainless steel or 18K Moonshine Gold—the brand’s proprietary yellow gold known for its enduring shine. The steel version has an anodised aluminium bezel and a stainless steel bracelet or vintage-inspired perforated leather strap. The Moonshine Gold iteration boasts a ceramic bezel; it will most likely appease Speedy collectors, particularly those with an affinity for Omega’s long-standing role as stewards of the Olympic Games.

Notably, each watch bears an attractive white opaline dial; the background to three dark grey timing scales in a 1940s “snail” design. Of course, this Speedmaster Chronoscope is special in its own right. For the most part, the overall look of the Speedmaster has remained true to its 1957 origins. This Speedmaster, however, adopts Omega’s Chronoscope design from 2021, including the storied tachymeter scale, along with a telemeter, and pulsometer scale—essentially, three different measurements on the wrist.

While the technical nature of this timepiece won’t interest some, others will revel in its theatrics. Turn over each timepiece, and instead of a transparent crystal caseback, there is a stamped medallion featuring a mirror-polished Paris 2024 logo, along with “Paris 2024” and the Olympic Rings—a subtle nod to this year’s games.

Powering this Olympiad offering—and ensuring the greatest level of accuracy—is the Co-Axial Master Chronometer Calibre 9908 and 9909, certified by METAS.

A Speedmaster to commemorate the Olympic Games was as sure a bet as Mondo Deplantis winning gold in the men’s pole vault—especially after Omega revealed its Olympic-edition Seamaster Diver 300m “Paris 2024” last year—but they delivered a great addition to the legacy collection, without gimmickry.

However, the all-gold Speedmaster is 85K at the top end of the scale, which is a lot of money for a watch of this stature. By comparison, the immaculate Speedmaster Moonshine gold with a sun-brushed green PVD “step” dial is 15K cheaper, albeit without the Chronoscope complications.

—

The Omega Speedmaster Chronoscope in stainless steel with a leather strap is priced at $15,725; stainless steel with steel bracelet at $16,275; 18k Moonshine Gold on leather strap $54,325; and 18k Moonshine Gold with matching gold bracelet $85,350, available at Omega boutiques now.

Discover the collection here

You may also like.

Here’s What Goes Into Making Jay-Z’s $1,800 Champagne

We put Armand de Brignac Blanc de Noirs Assemblage No. 4 under the microsope.

In our quest to locate the most exclusive and exciting wines for our readers, we usually ask the question, “How many bottles of this were made?” Often, we get a general response based on an annual average, although many Champagne houses simply respond, “We do not wish to communicate our quantities.” As far as we’re concerned, that’s pretty much like pleading the Fifth on the witness stand; yes, you’re not incriminating yourself, but anyone paying attention knows you’re probably guilty of something. In the case of some Champagne houses, that something is making a whole lot of bottles—millions of them—while creating an illusion of rarity.

We received the exact opposite reply regarding Armand de Brignac Blanc de Noirs Assemblage No. 4. Yasmin Allen, the company’s president and CEO, told us only 7,328 bottles would be released of this Pinot Noir offering. It’s good to know that with a sticker price of around $1,800, it’s highly limited, but it still makes one wonder what’s so exceptional about it.

Known by its nickname, Ace of Spades, for its distinctive and decorative metallic packaging, Armand de Brignac is owned by Louis Vuitton Moët Hennessy and Jay-Z and is produced by Champagne Cattier. Each bottle of Assemblage No. 4 is numbered; a small plate on the back reads “Assemblage Four, [X,XXX]/7,328, Disgorged: 20 April, 2023.” Prior to disgorgement, it spent seven years in the bottle on lees after primary fermentation mostly in stainless steel with a small amount in concrete. That’s the longest of the house’s Champagnes spent on the lees, but Allen says the winemaking team tasted along the way and would have disgorged earlier than planned if they’d felt the time was right.

Chef de cave, Alexandre Cattier, says the wine is sourced from some of the best Premier and Grand Cru Pinot Noir–producing villages in the Champagne region, including Chigny-les-Roses, Verzenay, Rilly-la-Montagne, Verzy, Ludes, Mailly-Champagne, and Ville-sur-Arce in the Aube département. This is considered a multi-vintage expression, using wine from a consecutive trio of vintages—2013, 2014, and 2015—to create an “intense and rich” blend. Seventy percent of the offering is from 2015 (hailed as one of the finest vintages in recent memory), with 15 percent each from the other two years.

This precisely crafted Champagne uses only the tête de cuvée juice, a highly selective extraction process. As Allen points out, “the winemakers solely take the first and freshest portion of the gentle cuvée grape press,” which assures that the finished wine will be the highest quality. Armand de Brignac used grapes from various sites and three different vintages so the final product would reflect the house signature style. This is the fourth release in a series that began with Assemblage No. 1. “Testing different levels of intensity of aromas with the balance of red and dark fruits has been a guiding principle between the Blanc de Noirs that followed,” Allen explains.

The CEO recommends allowing the Assemblage No. 4 to linger in your glass for a while, telling us, “Your palette will go on a journey, evolving from one incredible aroma to the next as the wine warms in your glass where it will open up to an extraordinary length.” We found it to have a gorgeous bouquet of raspberry and Mission fig with hints of river rock; as it opened, notes of toasted almond and just-baked brioche became noticeable. With striking acidity and a vein of minerality, it has luscious nectarine, passion fruit, candied orange peel, and red plum flavors with touches of beeswax and a whiff of baking spices on the enduring finish. We enjoyed our bottle with a roast chicken rubbed with butter and herbes de Provence and savored the final, extremely rare sip with a bit of Stilton. Unfortunately, the pairing possibilities are not infinite with this release; there are only 7,327 more ways to enjoy yours.