Innovation versus novelty: how the watch industry got it wrong

Amid growing suspicion that novelties are driven by marketing rather than horology, watchmakers have sought to regain balance by reviving and revitalising classics.

Related articles

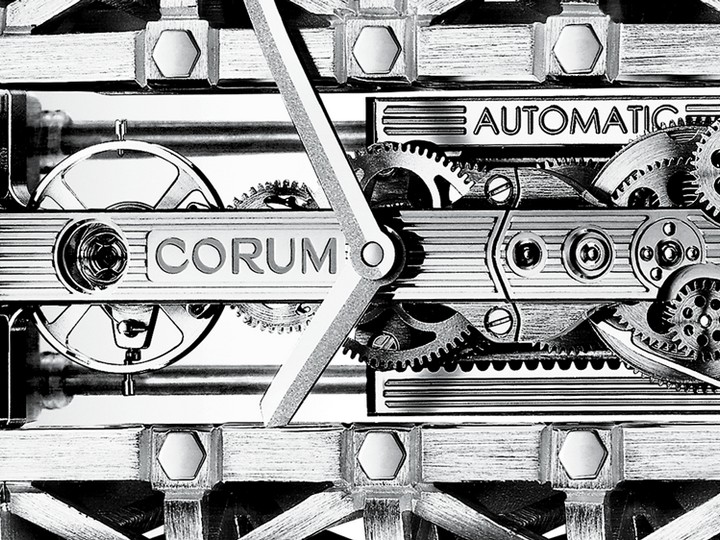

When the self-taught watchmaker Vincent Calabrese won a gold medal at the 1977 Salon International des Inventions de Genève, the watch industry looked in wonderment at his prizewinning movement. Calabrese had followed none of the usual horological rules. His movement was not particularly accurate, robust, or reliable.

What made his invention stand out was the way in which he had set all the gears in a straight line between the balance wheel and mainspring such that the viewer had an intuitive sense of how the mechanism kept time. Calabrese sold the movement to Corum, which enclosed it in a transparent crystal case and dubbed it the Golden Bridge. Variations are still being made by Corum today.

Few wristwatches can boast a four-decade lifespan. Most novelties last a single season, making headlines while the manufacturer is already secretly planning the following season’s attraction. The recent watch market downturn has been blamed partially on oversaturation: more novelty than collectors can absorb, with growing suspicion that novelties are driven by marketing rather than horology.

There is truth to these claims, and the industry has sought to regain balance by reviving and revitalising classics. (In addition to the 2017 Golden Bridge Rectangle, this past year has brought new releases of historical icons including the Longines Lindbergh and the Omega Railmaster.) These classics possess qualities of inventiveness that have long outlasted initial impressions, and the standards of deep innovation set by these iconic timepieces remain vital to contemporary watchmaking.

The distinction between deep innovation and superficial novelty can be stated simply: Deep innovation is a means to an end, whereas superficial novelty is undertaken for its own sake. But how deep innovation manifests is considerably more complex. It can apply to a watch’s appearance, its utility, its function, and even how it is made. One deep innovation may alter the wearer’s perception. Another may disrupt the entire watchmaking profession.

The Golden Bridge clearly falls into the former category. By fully exposing the mechanism, Calabrese exposes the wearer to a watchmaker’s view of time. In this formulation, time can be seen to unwind, moderated by the balance wheel’s inertia. This procedural understanding is more than just a perspective on technology. It also evokes a clockwork model of the cosmos, in which the universe is succumbing to entropy but process has a set pace — from which time itself emerges. By inventing an in-line watch movement, Calabrese has created a philosophical instrument.

Psychology can also be an impetus for deep innovation in watchmaking. Since the rise of the clock tower during the Middle Ages, timekeeping has organised society with ever-increasing precision. Clocks and watches govern every aspect of modern life, accentuating emotions ranging from anxiety to impatience.

Recognising the relationship between impatience and timekeeping, Hermès has released a watch with a mechanism dedicated to looking forward. L’Heure Impatiente, developed by the watchmaker Jean-Marc Wiederrecht and released earlier this year, has a subdial that can be set to a future time as much as 12 hours in advance. When the designated hour arrives, a countdown timer starts and runs for 60 minutes before striking a chime.

Elements of this watch have a historical precedent. The chime is reminiscent of alarm watches such as the Jaeger-LeCoultre Memovox, and countdown timers are found on timepieces designed for regattas such as the Rolex Yacht-Master. The innovation is in how these are combined to give expression to impatience, to provide a mechanism for controlling it, and perhaps even to deconstruct this very human trait by reducing it to clockwork.

If Calabrese’s movement can be construed as a philosophical instrument, Wiederrecht’s achievement has been to invent a kind of psychological automaton.

When Charles Lindbergh set out to develop the ultimate flight navigation watch in 1930, he was already the world’s most celebrated aviator, and the challenges of his 1927 solo trans-Atlantic flight directly informed the design of his timepiece. Lindbergh had made his way across the ocean by dead reckoning — charting his course with compass and airspeed indicator — because navigation by the stars was too demanding for one man flying alone. (The standard technique, originally conceived for navigation at sea, required a chronometer and a sextant as well as reams of star charts and reduction tables.) Lindbergh sought to simplify celestial calculations on the fly with an oversize wrist instrument designed specifically to work with the Navy’s state-of-the-art “hour-angle” system.

The Hour Angle watch that he invented in collaboration with Longines was re-released this year to coincide with the 90th anniversary of his most famous flight, which was timed by the Swiss watchmaker. It incorporated task-specific features such as an external bezel that could be adjusted to indicate the equation of time (the seasonally variable time of day as measured on a sundial), as well as a rotating inner disc for calibrating the timepiece to the exact second according to radio beacons. The purposefulness of these functions, which benefited pilots for decades, make them textbook examples of deep innovation.

Functional inventiveness persists in watchmaking today, embodied by the Einsatzzeitmesser (EZM) series of watches by Sinn. Einsatzzeitmesser means “mission timer,” and Sinn fully embraces the name: Many EZMs are developed in collaboration with a specific sector of the German government to serve the focused needs of personnel ranging from customs police to military divers. Function guides every attribute of these timepieces, and is guided in turn by the demands of the intended mission.

The new EZM 12 is exemplary. Built for use by helicopter paramedics, the watch has an internal bezel marked to measure time elapsed from the moment of dispatch, an external bezel for countdowns, and a pulsometer with a four-way sweep-seconds hand so that a pulse reading can be initiated every 15 seconds. (A chronograph wouldn’t serve the purpose since operation requires two hands.) Even the watch case is task-specific: Both the strap and the external bezel can be removed so that the timepiece can be completely scrubbed down and sterilised between missions.

Purpose-driven innovation is not necessarily limited to external features and indications. Back in 1957, Omega took on one of the greatest impediments to timekeeping precision by developing a watch impervious to magnetism. The Railmaster was intended for engineers who encounter strong electromagnetic fields on the job. (The conditions of railroad engineering gave the watch its name, but it could equally serve the needs of electrical engineers running high-energy experiments.) Electromagnetic fields affect performance of a watch movement by magnetising components, distorting timekeeping parameters such as the torque of the balance spring. Omega overcame this problem by encapsulating the movement in a Faraday cage — a soft iron enclosure that guides magnetic field-lines around the mechanism inside.

This simple intervention can protect movements from fields of up to approximately 1,000 gauss, and Omega was not alone in exploiting it. Other antimagnetic watches of the same era include the Rolex Milgauss and the IWC Ingenieur. (Iterations of both are still in production.) The problem is that when fields get strong enough, they pass through any amount of iron shielding. To make a watch truly antimagnetic requires that the movement be free of components attracted to magnets.

The new Omega Railmaster of 2017 meets this requirement. While the case and dial design are evocative of the 1957 model, the movement is entirely made out of amagnetic materials (such as a titanium balance wheel and silicon hairspring). As a result, the soft iron inner casing is no longer needed, and the antimagnetic protection has been bolstered to beyond 15,000 gauss.

This deep innovation predates the 60th anniversary Railmaster, having originally been implemented in the Omega Aqua Terra of 2013. Yet it is emblematic of how deep innovation inspires iteration based on new technologies and changing conditions. Observing the growing strength of electromagnetic fields in the modern world, Omega recognised an alternate kind of countermeasure with the development of the silicon hairspring in the early 21st century.

Superficial novelty stands out for a season before being supplanted and forgotten; deep innovation is self-perpetuating.

In the early 2000s, Patek Philippe formed an Advanced Research Program, formally institutionalising deep innovation. The initial focus was on silicon. In addition to being amagnetic, the material has desirable qualities ranging from smoothness to durability, and production techniques adapted from the computer industry allow for ultra-high-precision fabrication.

In collaboration with Rolex and the Swatch Group, Patek invested in basic research at the Centre Suisse d’Electronique et Microtechnique that facilitated the brand’s first silicon escape wheel, balance spring, and balance wheel. Each was initially built into a limited-edition Advanced Research timepiece, culminating in the 2011 release of the Ref. 5550 Perpetual Calendar Advanced Research featuring an all-silicon escapement.

The Advanced Research watches were more than mere showpieces. They prototyped silicon technologies that have subsequently benefited the majority of Patek Philippe wristwatches. They were means to an end, the goal being fundamental improvement of chronometry.

This year, Patek has taken the Advanced Research Program in a new direction. In addition to testing a novel curvature for the silicon balance spring, the company is experimenting for the first time with a “compliant” component: a single piece of flexible steel that serves the purpose of many conventional parts just by how it bends.

As was the case with silicon, compliant fabrication adapts research from other industries. For instance, compliant parts are used for mechanical control of astronomical telescopes. In the new Ref. 5650G Aquanaut Travel Time Advanced Research, the compliant part is used to manually adjust the GMT mechanism.

The genius of compliant fabrication is that gears and pivots can be replaced with geometry. In the 5650G, one piece of metal supplants more than two dozen conventional parts, closing tolerances, eliminating friction and obviating maintenance.

As compliance spreads into future movements, chronometry and durability are likely to improve. But the invention could be more deeply disruptive. Compliant mechanisms have to potential to upset centuries of watchmaking by fundamentally changing movement architecture and assembly. In the hands of Vincent Calabrese, they may even evoke a new cosmology.

Subscribe to the Newsletter

Recommended for you

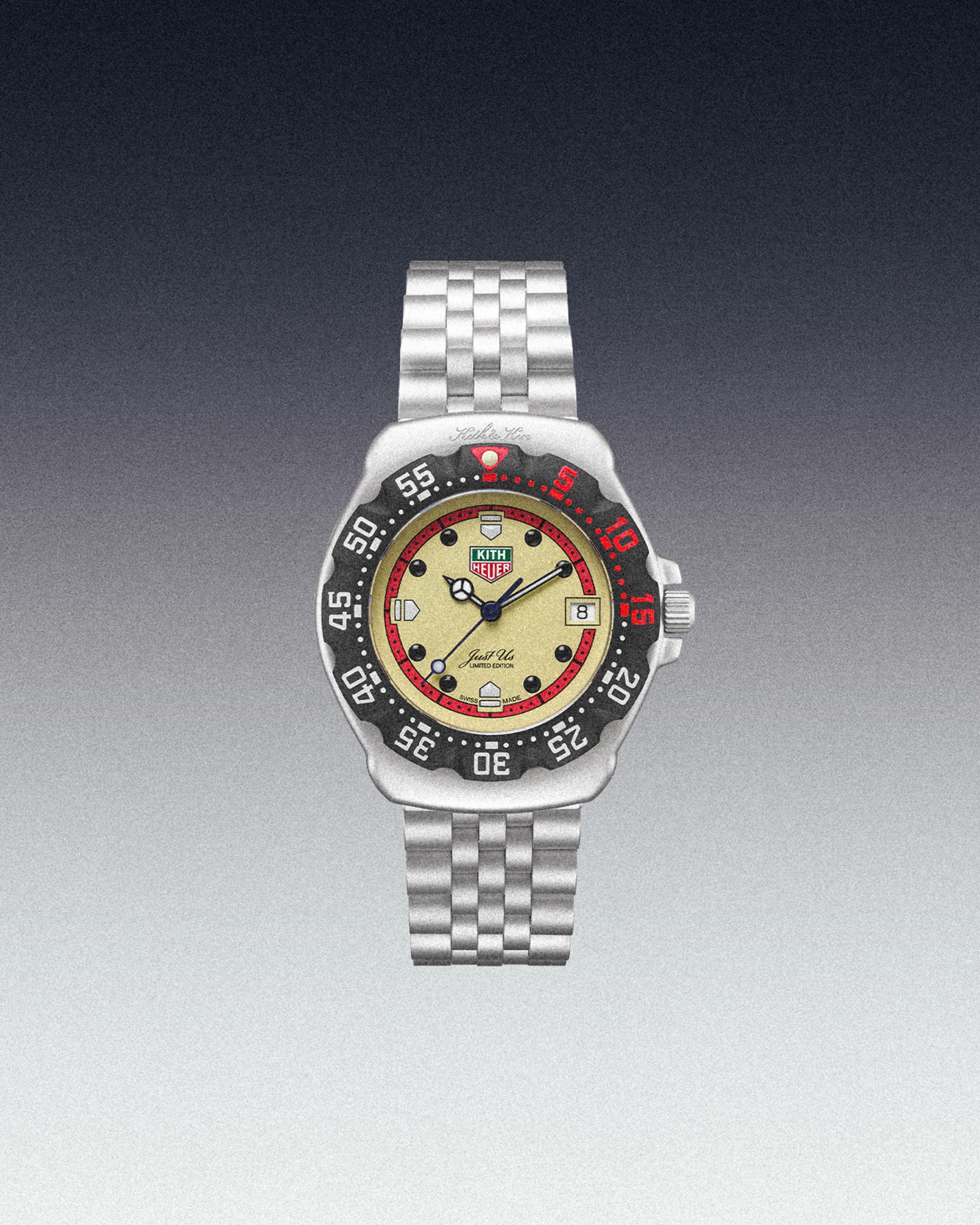

Watch of the Week: TAG Heuer Formula 1 | Kith

The legendary sports watch returns, but with an unexpected twist.

By Josh Bozin

May 2, 2024

Omega Reveals a New Speedmaster Ahead of the Paris 2024 Olympics

Your first look at the new Speedmaster Chronoscope, designed in the colour theme of the Paris Olympics.

By Josh Bozin

April 26, 2024

You may also like.

You may also like.

Watch of the Week: TAG Heuer Formula 1 | Kith

The legendary sports watch returns, but with an unexpected twist.

Over the last few years, watch pundits have predicted the return of the eccentric TAG Heuer Formula 1, in some shape or form. It was all but confirmed when TAG Heuer’s heritage director, Nicholas Biebuyck, teased a slew of vintage models on his Instagram account in the aftermath of last year’s Watches & Wonders 2023 in Geneva. And when speaking with Frédéric Arnault at last year’s trade fair, the former CEO asked me directly if the brand were to relaunch its legacy Formula 1 collection, loved by collectors globally, how should they go about it?

My answer to the baited entreaty definitely didn’t mention a collaboration with Ronnie Fieg of Kith, one of the world’s biggest streetwear fashion labels. Still, here we are: the TAG Heuer Formula 1 is officially back and as colourful as ever.

As the watch industry enters its hype era—in recent years, we’ve seen MoonSwatches, Scuba Fifty Fathoms, and John Mayer G-Shocks—the new Formula 1 x Kith collaboration might be the coolest yet.

Here’s the lowdown: overnight, TAG Heuer, together with Kith, took to socials to unveil a special, limited-edition collection of Formula 1 timepieces, inspired by the original collection from the 1980s. There are 10 new watches, all limited, with some designed on a stainless steel bracelet and some on an upgraded rubber strap; both options nod to the originals.

Seven are exclusive to Kith and its global stores (New York, Los Angeles, Miami, Hawaii, Tokyo, Toronto, and Paris, to be specific), and are made in an abundance of colours. Two are exclusive to TAG Heuer; and one is “shared” between TAG Heuer and Kith—this is a highlight of the collection, in our opinion. A faithful play on the original composite quartz watch from 1986, this model, limited to just 1,350 pieces globally, features the classic black bezel with red accents, a stainless steel bracelet, and that creamy eggshell dial, in all of its vintage-inspired glory. There’s no doubt that this particular model will present as pure nostalgia for those old enough to remember when the original TAG Heuer Formula 1 made its debut.

Of course, throughout the collection, Fieg’s design cues are punctuated: the “TAG” is replaced with “Kith,” forming a contentious new brand name for this specific release, as well as Kith’s slogan, “Just Us.”

Collectors and purists alike will appreciate the dedication to the original Formula 1 collection: features like the 35mm Arnite cases—sourced from the original 80s-era supplier—the form hour hand, a triangle with a dot inside at 12 o’clock, indices that alternate every quarter between shields and dots, and a contrasting minuterie, are all welcomed design specs that make this collaboration so great.

Every TAG Heuer Formula 1 | Kith timepiece will be presented in an eye-catching box that complements the fun and colour theme of Formula 1 but drives home the premium status of this collaboration. On that note, at $2,200 a piece, this isn’t exactly an approachable quartz watch but reflects the exclusive nature of Fieg’s Kith brand and the pieces he designs (largely limited-edition).

So, what do we think? It’s important not to understate the significance of the arrival of the TAG Heuer Formula 1 in 1986, in what would prove integral in setting up the brand for success throughout the 90’s—it was the very first watch collection to have “TAG Heuer” branding, after all—but also in helping to establish a new generation of watch consumer. Like Fieg, many millennial enthusiasts will recall their sentimental ties with the Formula 1, often their first timepiece in their horological journey.

This is as faithful of a reissue as we’ll get from TAG Heuer right now, and budding watch fans should be pleased with the result. To TAG Heuer’s credit, a great deal of research has gone into perfecting and replicating this iconic collection’s proportions, materials, and aesthetic for the modern-day consumer. Sure, it would have been nice to see a full lume dial, a distinguishing feature on some of the original pieces—why this wasn’t done is lost on me—and perhaps a more approachable price point, but there’s no doubt these will become an instant hit in the days to come.

—

The TAG Heuer Formula 1 | Kith collection will be available on Friday, May 3rd, exclusively in-store at select TAG Heuer and Kith locations in Miami, and available starting Monday, May 6th, at select TAG Heuer boutiques, all Kith shops, and online at Kith.com. To see the full collection, visit tagheuer.com

You may also like.

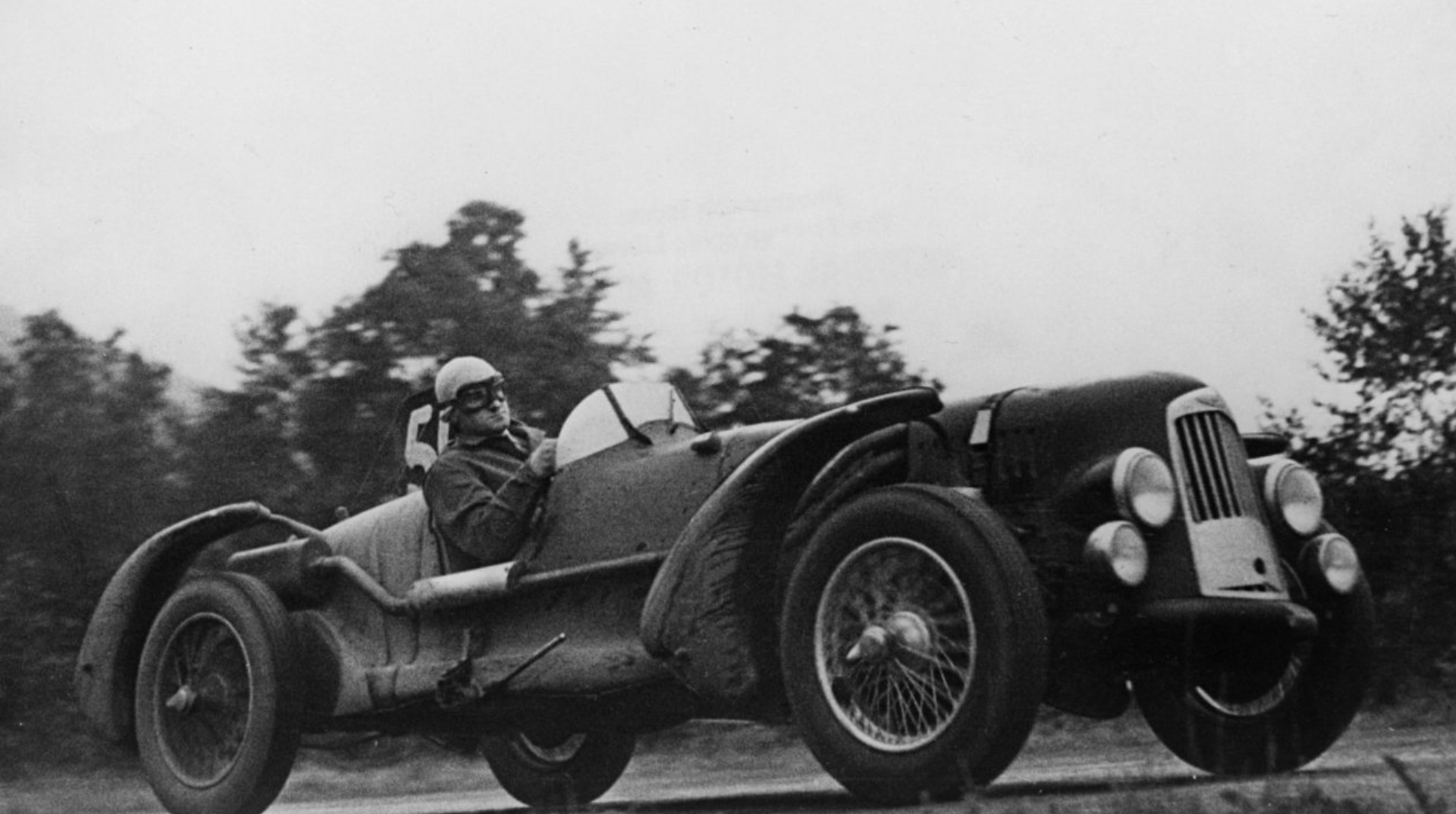

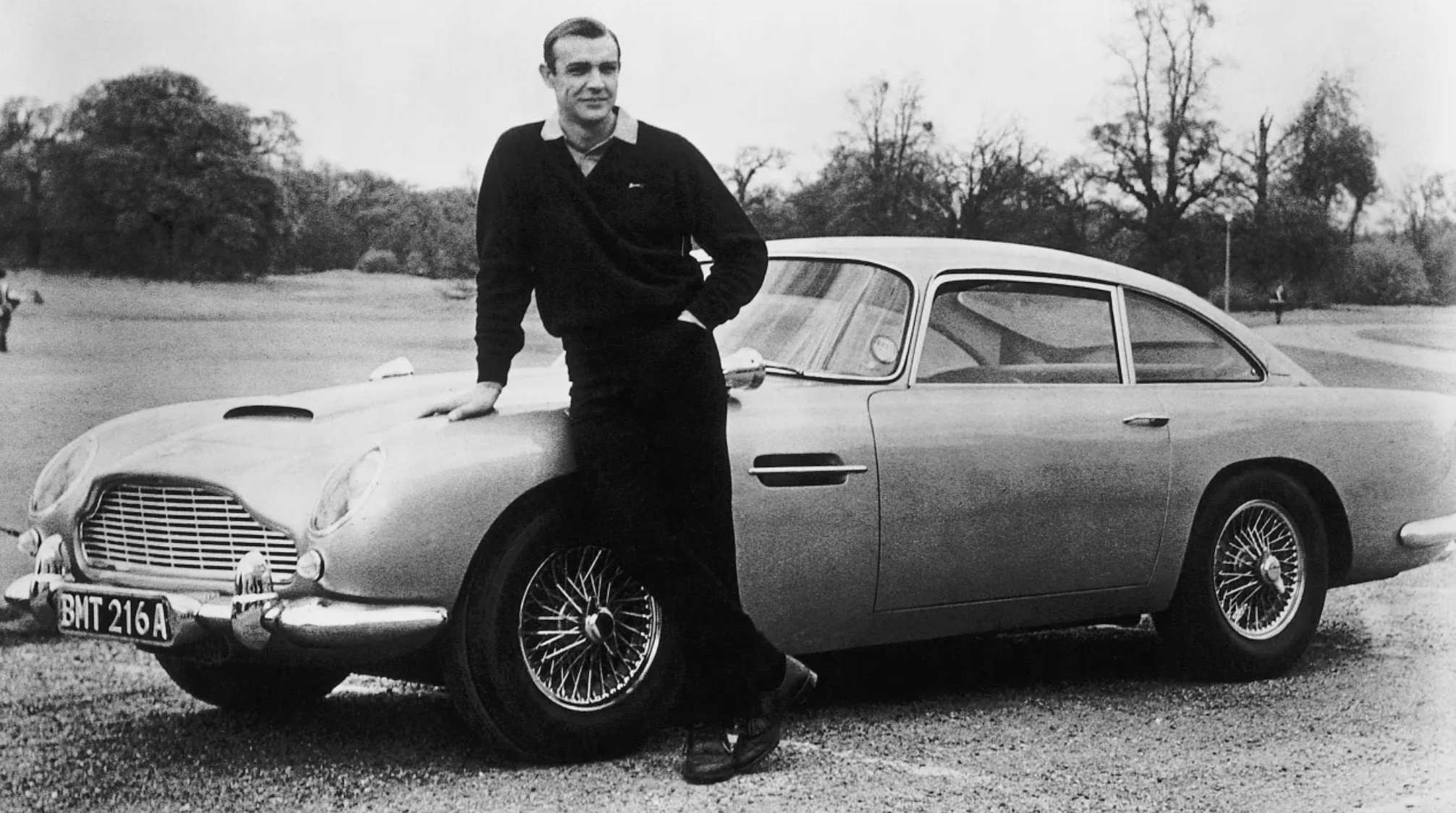

8 Fascinating Facts You Didn’t Know About Aston Martin

The British sports car company is most famous as the vehicle of choice for James Bond, but Aston Martin has an interesting history beyond 007.

Aston Martin will forever be associated with James Bond, ever since everyone’s favourite spy took delivery of his signature silver DB5 in the 1964 film Goldfinger. But there’s a lot more to the history of this famed British sports car brand beyond its association with the fictional British Secret Service agent.

Let’s dive into the long and colourful history of Aston Martin.

You may also like.

What Venice’s New Tourist Tax Means for Your Next Trip

The Italian city will now charge visitors an entry fee during peak season.

Visiting the Floating City just got a bit more expensive.

Venice is officially the first metropolis in the world to start implementing a day-trip fee in an effort to help the Italian hot spot combat overtourism during peak season, The Associated Press reported. The new program, which went into effect, requires travellers to cough up roughly €5 (about $AUD8.50) per person before they can explore the city’s canals and historic sites. Back in January, Venice also announced that starting in June, it would cap the size of tourist groups to 25 people and prohibit loudspeakers in the city centre and the islands of Murano, Burano, and Torcello.

“We need to find a new balance between the tourists and residents,’ Simone Venturini, the city’s top tourism official, told AP News. “We need to safeguard the spaces of the residents, of course, and we need to discourage the arrival of day-trippers on some particular days.”

During this trial phase, the fee only applies to the 29 days deemed the busiest—between April 25 and July 14—and tickets will remain valid from 8:30 am to 4 pm. Visitors under 14 years of age will be allowed in free of charge in addition to guests with hotel reservations. However, the latter must apply online beforehand to request an exemption. Day-trippers can also pre-pay for tickets online via the city’s official tourism site or snap them up in person at the Santa Lucia train station.

“With courage and great humility, we are introducing this system because we want to give a future to Venice and leave this heritage of humanity to future generations,” Venice Mayor Luigi Brugnaro said in a statement on X (formerly known as Twitter) regarding the city’s much-talked-about entry fee.

Despite the mayor’s backing, it’s apparent that residents weren’t totally pleased with the program. The regulation led to protests and riots outside of the train station, The Independent reported. “We are against this measure because it will do nothing to stop overtourism,” resident Cristina Romieri told the outlet. “Moreover, it is such a complex regulation with so many exceptions that it will also be difficult to enforce it.”

While Venice is the first city to carry out the new day-tripper fee, several other European locales have introduced or raised tourist taxes to fend off large crowds and boost the local economy. Most recently, Barcelona increased its city-wide tourist tax. Similarly, you’ll have to pay an extra “climate crisis resilience” tax if you plan on visiting Greece that will fund the country’s disaster recovery projects.

You may also like.

Omega Reveals a New Speedmaster Ahead of the Paris 2024 Olympics

Your first look at the new Speedmaster Chronoscope, designed in the colour theme of the Paris Olympics.

The starters are on the blocks, and with less than 100 days to go until the Paris 2024 Olympics, luxury Swiss watchmaker Omega was bound to release something spectacular to mark its bragging rights as the official timekeeper for the Summer Games. Enter the new 43mm Speedmaster Chronoscope, available in new colourways—gold, black, and white—in line with the colour theme of the Olympic Games in Paris this July.

So, what do we get in this nicely-wrapped, Olympics-inspired package? Technically, there are four new podium-worthy iterations of the iconic Speedmaster.

The new versions present handsomely in stainless steel or 18K Moonshine Gold—the brand’s proprietary yellow gold known for its enduring shine. The steel version has an anodised aluminium bezel and a stainless steel bracelet or vintage-inspired perforated leather strap. The Moonshine Gold iteration boasts a ceramic bezel; it will most likely appease Speedy collectors, particularly those with an affinity for Omega’s long-standing role as stewards of the Olympic Games.

Notably, each watch bears an attractive white opaline dial; the background to three dark grey timing scales in a 1940s “snail” design. Of course, this Speedmaster Chronoscope is special in its own right. For the most part, the overall look of the Speedmaster has remained true to its 1957 origins. This Speedmaster, however, adopts Omega’s Chronoscope design from 2021, including the storied tachymeter scale, along with a telemeter, and pulsometer scale—essentially, three different measurements on the wrist.

While the technical nature of this timepiece won’t interest some, others will revel in its theatrics. Turn over each timepiece, and instead of a transparent crystal caseback, there is a stamped medallion featuring a mirror-polished Paris 2024 logo, along with “Paris 2024” and the Olympic Rings—a subtle nod to this year’s games.

Powering this Olympiad offering—and ensuring the greatest level of accuracy—is the Co-Axial Master Chronometer Calibre 9908 and 9909, certified by METAS.

A Speedmaster to commemorate the Olympic Games was as sure a bet as Mondo Deplantis winning gold in the men’s pole vault—especially after Omega revealed its Olympic-edition Seamaster Diver 300m “Paris 2024” last year—but they delivered a great addition to the legacy collection, without gimmickry.

However, the all-gold Speedmaster is 85K at the top end of the scale, which is a lot of money for a watch of this stature. By comparison, the immaculate Speedmaster Moonshine gold with a sun-brushed green PVD “step” dial is 15K cheaper, albeit without the Chronoscope complications.

—

The Omega Speedmaster Chronoscope in stainless steel with a leather strap is priced at $15,725; stainless steel with steel bracelet at $16,275; 18k Moonshine Gold on leather strap $54,325; and 18k Moonshine Gold with matching gold bracelet $85,350, available at Omega boutiques now.

Discover the collection here

You may also like.

Here’s What Goes Into Making Jay-Z’s $1,800 Champagne

We put Armand de Brignac Blanc de Noirs Assemblage No. 4 under the microsope.

In our quest to locate the most exclusive and exciting wines for our readers, we usually ask the question, “How many bottles of this were made?” Often, we get a general response based on an annual average, although many Champagne houses simply respond, “We do not wish to communicate our quantities.” As far as we’re concerned, that’s pretty much like pleading the Fifth on the witness stand; yes, you’re not incriminating yourself, but anyone paying attention knows you’re probably guilty of something. In the case of some Champagne houses, that something is making a whole lot of bottles—millions of them—while creating an illusion of rarity.

We received the exact opposite reply regarding Armand de Brignac Blanc de Noirs Assemblage No. 4. Yasmin Allen, the company’s president and CEO, told us only 7,328 bottles would be released of this Pinot Noir offering. It’s good to know that with a sticker price of around $1,800, it’s highly limited, but it still makes one wonder what’s so exceptional about it.

Known by its nickname, Ace of Spades, for its distinctive and decorative metallic packaging, Armand de Brignac is owned by Louis Vuitton Moët Hennessy and Jay-Z and is produced by Champagne Cattier. Each bottle of Assemblage No. 4 is numbered; a small plate on the back reads “Assemblage Four, [X,XXX]/7,328, Disgorged: 20 April, 2023.” Prior to disgorgement, it spent seven years in the bottle on lees after primary fermentation mostly in stainless steel with a small amount in concrete. That’s the longest of the house’s Champagnes spent on the lees, but Allen says the winemaking team tasted along the way and would have disgorged earlier than planned if they’d felt the time was right.

Chef de cave, Alexandre Cattier, says the wine is sourced from some of the best Premier and Grand Cru Pinot Noir–producing villages in the Champagne region, including Chigny-les-Roses, Verzenay, Rilly-la-Montagne, Verzy, Ludes, Mailly-Champagne, and Ville-sur-Arce in the Aube département. This is considered a multi-vintage expression, using wine from a consecutive trio of vintages—2013, 2014, and 2015—to create an “intense and rich” blend. Seventy percent of the offering is from 2015 (hailed as one of the finest vintages in recent memory), with 15 percent each from the other two years.

This precisely crafted Champagne uses only the tête de cuvée juice, a highly selective extraction process. As Allen points out, “the winemakers solely take the first and freshest portion of the gentle cuvée grape press,” which assures that the finished wine will be the highest quality. Armand de Brignac used grapes from various sites and three different vintages so the final product would reflect the house signature style. This is the fourth release in a series that began with Assemblage No. 1. “Testing different levels of intensity of aromas with the balance of red and dark fruits has been a guiding principle between the Blanc de Noirs that followed,” Allen explains.

The CEO recommends allowing the Assemblage No. 4 to linger in your glass for a while, telling us, “Your palette will go on a journey, evolving from one incredible aroma to the next as the wine warms in your glass where it will open up to an extraordinary length.” We found it to have a gorgeous bouquet of raspberry and Mission fig with hints of river rock; as it opened, notes of toasted almond and just-baked brioche became noticeable. With striking acidity and a vein of minerality, it has luscious nectarine, passion fruit, candied orange peel, and red plum flavors with touches of beeswax and a whiff of baking spices on the enduring finish. We enjoyed our bottle with a roast chicken rubbed with butter and herbes de Provence and savored the final, extremely rare sip with a bit of Stilton. Unfortunately, the pairing possibilities are not infinite with this release; there are only 7,327 more ways to enjoy yours.