Polar Opposites

A journey north to one of the harshest, remotest spots on Earth couldn’t be more luxurious.

Related articles

A century ago, an expedition to the North Pole involved dog sleds and explorers in heavy, fur-lined clothes, windburned and famished after weeks of trudging across ice floes, finally planting their nations’ flags in the barren landscape. These days, if you’re a tourist, the only way to reach 90 degrees north latitude, the geographic North Pole, is aboard Le Commandant Charcot, a six-star hotel mated to a massive, 150-metre ice-breaking hull.

My wife, Cathy, and I are among the first group of tourists aboard Ponant’s new expedition icebreaker, the world’s only Polar Class 2–rated cruise ship (of seven levels of ice vessel, second only to research and military vessels in ability to manoeuvre in Arctic conditions). Our arrival on July 14 couldn’t be more different from explorer Robert Peary’s on April 6, 1909. On that date, he reported, he staked a small American flag—sewed by his wife—into the Pole, joined by four Inuits and his assistant, Matthew Henson, a Black explorer from Maine who was with Peary on his two previous Arctic expeditions. (Peary’s claim of being first to the Pole was quickly disputed by another American, Frederick Cook, who insisted he’d spent two days there a year earlier. Scholars now view both claims with skepticism.)

Our 300-plus party’s landing, on Bastille Day, features the captain of the French ship driving around in an all-terrain vehicle with massive wheels and an enormous tricolour flag on the back, guests dressed in stylish orange parkas celebrating on the ice, and La Marseillaise, France’s national anthem, blaring from loudspeakers. After an hour of taking selfies and building snow igloos in the icescape, with temperatures in the relatively balmy low 30s, we head back into our heated sanctuary for mulled wine and freshly baked croissants. Mission accomplished. Flags planted. Now, lunch.

As a kid, I was fascinated by stories of adventurers trying to reach the North Pole without any means of rescue. In the 19th century, most of their attempts ended in disaster—ships getting trapped in the ice, a hydrogen balloon crashing, even cannibalism. It wasn’t until Cook and Peary reportedly set foot there that the race to the North Pole was really on. Norwegian Roald Amundsen, the first to reach the South Pole, in 1911, is credited with being the first to document a trip over the North Pole, which he did in 1926 in the airship Norge. In 1977, the nuclear-powered icebreaker Arktika became the first surface vessel to make it to the North Pole. Since then, only 18 other ships have completed the voyage.

Visiting the North Pole seemed about as likely for me as walking on the Moon. It wasn’t even on my bucket list. Then came Le Commandant Charcot, which was named after France’s most beloved polar explorer and reportedly cost about US$430 million (around $655 million) to build. The irony of visiting one of the planet’s most remote and inhospitable points while travelling in the lap of luxury doesn’t escape me or anyone else I speak with on the voyage. Danie Ferreira, from Cape Town, South Africa, describes it as “an ensemble of contradictions bordering on the absurd”. Ferreira, who is on board with his wife, Suzette, is a veteran of early-explorer-style high-Arctic journeys, months-long treks involving dog sleds and real toil and suffering. He booked this trip to obtain an official North Pole stamp for an upcoming two-volume collection of his photographs, Out in the Cold, documenting his polar adventures. “Reserving the cabin felt like a betrayal of my expeditionary philosophy,” he says with a laugh.

Then, like the rest of us, he embraces the contradictions. “This is like the first time I saw the raw artistry of Cirque du Soleil,” he explains. “Everything is beyond my wildest expectations, unrelatable to anything I’ve experienced.”

The 17-day itinerary launches from the Norwegian settlement of Longyearbyen, Svalbard, the northernmost town in the Arctic Circle, and heads 1,186 nautical miles to the North Pole, then back again. As a floating hotel, the vessel is exceptional: 123 balconied staterooms and suites, the most expensive among them duplexes with butler service (prices range from around $58,000 to $136,000 per person, double occupancy); a spa with a sauna, massage therapists, and aestheticians; a gym and heated indoor pool. The boat weighs more than 35,000 tons, enabling it to break ice floes like “a chocolate bar into little pieces, rather than slice through them”, according to Captain Patrick Marchesseau. Six-metre-wide stainless-steel propellers, he adds, were designed to “chew ice like a blender”.

Marchesseau, a tall, lanky, 40-ish mariner from Brittany, impeccable in his navy uniform but rocking royal-blue boat shoes, proves to be a charming host. Never short of a good quip, he’s one of three experienced ice captains who alternate at the helm of Charcot throughout the year. He began piloting Ponant ships through drifting ice floes in Antarctica in 2009, when he took the helm of Le Diamant, Ponant’s first expedition vessel. “An epic introduction,” Marchesseau calls those early voyages, but the isolated, icebound North Pole aboard a larger, more complicated vessel is potentially an even thornier challenge. “We’ll first sail east where the ice is less concentrated and then enter the pack at 81 degrees,” he tells a lecture hall filled with passengers on day one. “We don’t plan to stop until we get to the North Pole.”

Around us, the majority of the other 101 guests are older French couples; there are also a few extended families, some other Europeans, mostly German and Dutch, as well as 10 Americans. Among the supporting cast are six research scientists and 221 staff, including 18 naturalist guides from a variety of countries.

The first six days are more about the journey than the destination. Cathy and I settle into our comfortable stateroom, enjoy the ocean views from our balcony, make friends with other guests and naturalists, frequent the spa, and indulge in the contemporary French cuisine at Nuna, which is often jarred by ice passing under the hull, as well as at the more casual Sila (Inuit for “sky”). There are the usual cruise events: the officers’ gala, wine pairings, daily French pastries, Broadway-style shows, opera singers and concert pianists. Initially, I worry about “Groundhog Day” setting in, but once we hit patchy ice floes on day two, it’s clear that the polar party is on. The next day, we’re ensconced in the ice pack.

Veterans of Arctic journeys immediately feel at home. Ferreira, often found on the observation deck 15 metres above the ice with his long-lensed cameras, is in his element snapping different patterns and colours of the frozen landscape. “It feels like combining low-level flying with an out-of-body experience,” he says. “Whenever the hull shudders against the ice, I have a reality check.”

“I came back because I love this ice,” adds American Gin Millsap, who with her husband, Jim, visited the North Pole in 2015 aboard the Russian nuclear icebreaker Fifty Years of Victory, which for obvious reasons is no longer a viable option for Americans and many Europeans. “I love the peace, beauty and calmness.”

It is easy to bliss out on the endless barren vistas, constantly morphing into new shapes, contours and shades of white as the weather moves from bright sunshine to howling snowstorms—sometimes within the course of a few hours. I spend a lot of time on the cold, windswept bow, looking at the snow patterns, ridges and rivers flowing within the pale landscape as the boat crunches through the ice. It feels like being in a black-and-white movie, with no colours except the turquoise bottoms of ice blocks overturned by the boat. Beautiful, lonely, mesmerising.

Rather than a solid landmass, the Arctic ice pack is actually millions of square kilometres of ice floes, slowly pushed around by wind and currents. The size varies according to season: this past winter, the ice was at its fifth-lowest level on record, encompassing 14.6 million square kilometres, while during our cruise it was 4.7 million square kilometres, the 10th-lowest summer number on record. There are myriad ice types—young ice, pancake ice, ice cake, brash ice, fast ice—but the two that our ice pilot, Geir-Martin Leinebø, cares about are first-year ice and old ice. The thinness of the former provides the ideal route to the Pole, while the denseness of the aged variety can result in three-to-eight-metre-high ridges that are potentially impassable. Leinebø is no novice: in his day job, he’s the captain of Norway’s naval icebreaker, KV Svalbard, the first Norwegian vessel to reach the North Pole, in 2019.

It’s not a matter of just pointing the boat due north and firing up the engine. Leinebø zigzags through the floes. A morning satellite feed and special software aid in determining the best route; the ship’s helicopter sometimes scouts 65 or so kilometres ahead, and there’s a sonar called the Sea Ice Monitoring System (SIMS). But mostly Leinebø uses his eyes. “You look for the weakest parts of the ice—you avoid the ridges because that means thickness and instead look for water,” he says. “If the ‘water sky’ in the distance is dark, it’s reflecting water like a mirror, so you head in that direction.”

Everyone on the bridge is surprised by the lack of multi-year ice, but with more than a hint of disquietude. Though we don’t have to ram our way through frozen ridges, the advance of climate change couldn’t be more apparent. Environmentalists call the Arctic ice sheet the canary in the coal mine of the planet’s climate change for good reason: it is happening here first. “It’s not right,” mutters Leinebø. “There’s just too much open water for July. Really scary.”

The Arctic ice sheet has shrunk to about half its 1985 size, and as both mariners and scientists on board note, the quality of the ice is deteriorating. “It’s happening faster than our models predicted,” says Marisol Maddox, senior arctic analyst at the Polar Institute of the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars. “We’re seeing major events like Greenland’s ice sheet melting and sliding into the ocean—that wasn’t forecasted until 2070.” The consensus had been that the Arctic would be ice-free by 2050, but many scientists now expect that day to come in the 2030s.

That deterioration, it turns out, is why the three teams of scientists are on the voyage—two studying the ice and the other assessing climate change’s impact on plankton. As part of its commitment to sustainability, Ponant has designed two research labs—one wet and one dry—on a lower deck. “We took the advice of many scientists for equipping these labs,” says Hugues Decamus, Charcot’s chief engineer, clearly proud of the nearly US$12 million facilities.

The combined size of the labs, along with a sonar room, a dedicated server for the scientists, and a meteorological station on the vessel’s top deck, totals 130 square metres—space that could have been used for revenue generation. Ponant also has two staterooms reserved for scientists on each voyage and provides grants for travel expenses. The line doesn’t cherrypick researchers but instead asks the independent Arctic Research Icebreaker Consortium (ARICE) to choose participants based on submissions.

The idea, says the vessel’s science officer on this voyage, Daphné Buiron, is to make the process transparent and minimise the appearance of greenwashing. “Yes, this alliance may deliver a positive public image for the company, but this ship shows we do real science on board,” she says. The labs will improve over time, adds Decamus, as the ship amasses more sophisticated equipment.

Research scientists and tourist vessels don’t typically mix. The former, wary of becoming mascots for the cruise lines’ sustainability marketing efforts, and cognisant of the less-than-pristine footprint of many vessels, tend to be wary. The cruise lines, for their part, see scientists as potentially high maintenance when paying customers should be the priority. But there seemed to be a meeting of the minds, or at least a détente, on Le Commandant Charcot.

“We discuss this a lot and are aware of the downsides, but also the positives,” says Franz von Bock und Polach, head of the institute for ship structural design and analysis at Hamburg University of Technology, specialising in the physics of sea ice. Not only does Charcot grant free access to these remote areas, but the ship will also collect data on the same route multiple times a year with equipment his team leaves on board, offering what scientists prize most: repeatability. “One transit doesn’t have much value,” he says. “But when you measure different seasons, regions and years, you build up a more complex picture.” So, more than just a research paper: forecasts of ice conditions for long-term planning by governments as the Arctic transforms.

Nils Haëntjens, from the University of Maine, is analysing five-millilitre drops of water on a high-tech McLane IFCB microscope. “The instrument captures more than 250,000 images of phytoplankton along the latitudinal transect,” he says. Charcot has doors in the wet lab that allow the scientists to take water samples, and in the bow, inlets take in water without contaminating it. Two freezers can preserve samples for further research back in university labs.

Even though the boat won’t stop, the captain and chief engineer clearly want to make the science missions work. Marchesseau dispatches the helicopter with the researchers and their gear 100 kilometres ahead, where they take core samples and measurements. I spot them in their red snowsuits, pulling sleds on an ice floe, as the boat passes. Startled to see living-colour humans on the ice after days of monochrome, I feel a pang of jealousy as I head for a caviar tasting.

The only other humans we encounter on the journey north are aboard Fifty Years of Victory, the Russian icebreaker. The 160-metre orange- and-black leviathan reached the North Pole a day earlier—its 59th visit—and is on its way back to Murmansk. It’s a classic East meets West moment: the icebreaker, launched just after the collapse of the Soviet Union, meeting the new standard of polar luxury.

The evening before Bastille Day, Le Commandant Charcot arrives at the North Pole. Because of the pinpoint precision of the GPS, Marchesseau has to navigate back and forth for about 20 minutes—with a bridge full of passengers hushing each other so as not to distract him—until he finds 90 degrees north. That final chaotic approach to the top of the world in the grey, windswept landscape looks like a kid’s Etch A Sketch on the chartplotter, but it is met with rousing cheers. The next morning, with good visibility and light winds, we spill out onto the ice for the celebration, followed by a polar plunge.

As guests pose in front of flags and mile markers for major cities, the naturalist guides, armed with rifles, establish a wide perimeter to guard against polar bears. The fearless creatures are highly intelligent, with razor-sharp teeth, hooked claws and the ability to sprint at 40 km/h. Males average about three metres tall and weigh around 700 kilos. They are loners that will kill anything—including other bears and even their own cubs. Cathy and I walk around the far edges of the perimeter to enjoy some solitude. Looking out over the white landscape, I know this is a milestone. But it feels odd that getting here didn’t involve any sweat or even a modicum of discomfort.

The rest of the week is an entirely different trip. On the return south, we see a huge male polar bear ambling on the ice, looking over his shoulder at us. It is our first sighting of the Arctic’s apex predator, and everyone crowds the observation lounge with long-lensed cameras. The next day, we see another male, this one smaller, running away from the ship. “They have many personalities,” says Steiner Aksnes, head of the expedition team, who has led scientists and film crews in the Arctic for 25 years. We see a dozen on the return to Svalbard, where 3,000 are scattered across the archipelago, outnumbering human residents.

The last five days we make six stops on different islands, travelling by Zodiac from Charcot to various beaches. On Lomfjorden, as we look on a hundred yards from shore, a mother polar bear protects her two cubs while a young male hovers in the background. On a Zodiac ride off Alkefjellet, the air is alive with birds, including tens of thousands of Brünnich’s guillemots as well as glaucous gulls and kittiwakes, which nest in that island’s cliffs, while a young male polar bear munches on a ring seal, chin glistening red.

On this part of the trip, the expedition team, mostly 30-something, free-spirited scientists whose areas of expertise range from botany to alpine trekking to whales, lead hikes across different landscapes. The jam-packed schedule sometimes involves three activities per day and includes following the reindeer on Palanderbukta, seeing a colony of 200 walruses on Kapp Lee, hiking the black tundra of Burgerbukta (boasting 3.8-cm-tall willows—said to be the smallest trees in the world and the largest on Svalbard—plus mosquitoes!), watching multiple species of whales breaching offshore, and kayaking the ice floes of Ekmanfjorden. Svalbard is a protected wilderness area, and the cruise lines tailor their schedules so vessels don’t overlap, giving visitors the impression they are setting foot on virgin land.

Chances to experience that sense of discovery and wonder, even slightly stage-managed ones, are dwindling along with the ice sheet and endangered wildlife. If a stunning trip to a frozen North Pole is on your bucket list, the time to go is now.

PARADIGM SHIP

For those studying polar ice, a berth aboard Le Commandant Charcot is like a winning lottery ticket. “This cruise ship is one of the few resources scientists can use, because nothing else can get there,” says G. Mark Miller, CEO of research-vessel builder Greenwater Marine Sciences Offshore (GMSO) and a former ship captain for the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). “Then factor in 80 percent of scientists who want to go to sea, can’t, because of the shortage of research vessels.”

Both Ponant and Viking have designed research labs aboard new expedition vessels as part of their sustainability initiatives. “Remote areas like Antarctica need more data—the typical research is just single data points,” says Damon Stanwell-Smith, Ph.D., head of science and sustainability at Viking. “Every scientist says more information is needed.” The twin sisterships Viking Octantis and Viking Polaris, which travel to Antarctica, Patagonia, the Great Lakes and Canada, have identical 35-square-metre labs, separated into wet and dry areas and fitted out with research equipment. In hangars below are military-grade rigid-hulled inflatables and two six-person yellow submersibles (the pair on Octantis are named John and Paul, while Polaris’s are George and Ringo). Unlike Ponant, Viking doesn’t have an independent association choose scientists for each voyage. Instead, it partners with the University of Cambridge, the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, and NOAA, which send their researchers to work with Viking’s onboard science officers.

“Some people think marine research is sticking some kids on a ship to take measurements,” says Stanwell-Smith. “But we know we can do first-rate science—not spin.” Other cruise lines are also embracing sustainability initiatives, with coral-reef-restoration projects and water-quality measurements, usually in partnership with universities. Just about every vessel has “citizen-scientist” research programs allowing guests the opportunity to count birds or pick up discarded plastic on beaches. So far, Ponant and Viking are the only lines with serious research labs. Ponant is adding science officers to other vessels in its fleet. As part of the initiatives, scientists deliver onboard lectures and sometimes invite passengers to assist in their research.

Given the shortage of research vessels, Stanwell-Smith thinks this passenger-funded system will coexist nicely with current NGO- and government-owned ships. “This could be a new paradigm for exploring the sea,” he says. “Maybe the next generation of research vessels will look like ours.”

Subscribe to the Newsletter

Recommended for you

Experience the opening ceremony of the Olympic Games Paris 2024 with Official Hospitality

The Olympic Games Paris 2024 offers a unique opportunity to experience the event in unprecedented style, thanks to exclusive hospitality packages offered by the official hospitality provider, On Location

May 15, 2024

Federer and Nadal Team Up in New Louis Vuitton Ad

Just in time for the French Open, Louis Vuitton serves up a winning new campaign.

You may also like.

You may also like.

Watch of the Week: Roger Dubuis Excalibur Spider Flyback Chronograph

Roger Dubuis unveils its innovative chronograph collection in Australia for the very first time.

When avant-garde Swiss watchmaker Roger Dubuis revealed its highly anticipated Chronograph Collection halfway through 2023, it was a testament to its haute horology department in creating such a technical marvel for everyday use. Long at the forefront of cutting-edge design and technological excellence, Roger Dubuis (pronounced Ro-ger Du-BWEE) is no stranger to such acclaim.

Now, fans down under will finally get a taste of the collection that made headlines, with the official Australian unveiling of its Chronograph Collection. Representing precision engineering, extraordinary craftsmanship, and audacious design, this collection, now in its fifth generation, continues to redefine the chronograph category.

Roger Dubuis Australia welcomes the Excalibur Spider Collection to the market, featuring the exquisite Excalibur Spider Flyback Chronograph, as well as the Excalibur Spider Revuelto Flyback Chronograph (a timepiece made in partnership with Lamborghini Squadra Corse). Each model speaks at lengths to the future of ‘Hyper Horology’—watchmaking, as Roger Dubuis puts it, that pushes the boundaries of traditional watchmaking.

“Roger Dubuis proposes a unique blend of contemporary design and haute horlogerie and the Excalibur Spider Flyback Chronograph is the perfect illustration of this craft,” says Sadry Keiser, Chief Marketing Officer. “For its design, we took inspiration from the MonovortexTM Split-Seconds Chronograph, while we decided to power the timepiece with an iconic complication, the flyback chronograph, also marking its come back in the Maison’s collections.”

The Excalibur Spider Flyback Chronograph is bold and flashy—a chronograph made to be seen, especially at its 45mm size. But Roger Dubuis wouldn’t have it any other way. The supercar-inspired watch is certainly captivating in the flesh. Its multi-dimensional design reveals different layers of technical genius as you spend time with it: from its case crafted from lightweight carbon to its hyper-resistant ceramic bezel, black DLC titanium crown, open case back with sapphire crystal, and elegant rubber strap to tie the watch together, it’s a sporty yet incredibly refined timepiece.

The new RD780 chronograph calibre powers the chronograph, a movement fully integrated with two patents: one linked to the second hand of the chronograph and the other to the display of the minute counter. The chronograph also features a flyback function.

The complete set is now available at the Sydney Boutique for those wishing to see the Roger Dubuis Chronograph Collection firsthand.

—

Model: Roger Dubuis Excalibur Spider Flyback Chronograph

Diameter: 45mm

Material: C-SMC Carbon case

Water resistance: 100m

Movement: RD780 calibre

Complication: Chronograph, date

Functions: hours, minutes, and central seconds

Power reserve: 72 hours

Bracelet: Black rubber strap

Availability: upon request

Price: $150,000

You may also like.

Federer and Nadal Team Up in New Louis Vuitton Ad

Just in time for the French Open, Louis Vuitton serves up a winning new campaign.

They have scaled the dizzying heights of tennis, and now great rivals and friends Roger Federer and friend Rafael Nadal climb a majestic mountaintop in the new Louis Vuitton campaign.

The latest installment of the LV’s storied Core Values series of ads, once again shot by renowned portrait photographer Annie Leibovitz, reunites two tennis legends who have not faced off against each other since Wimbledon 2019. (Federer retired in 2022 and in his last match teamed up with Nadal in doubles, with the pair famously crying and holding hands afterwards.)

Three thousand metres high in the Italian Dolomites and in less familiar attire than their usual on-court drag, Federer sports a classic Monogram Christopher Backpack that is every bit as elegant as his balletic prowess, while Nadal’s is a fittingly dynamic Monogram Eclipse version.

The campaign recalls the brand’s 2010 grouping of soccer legends Diego Maradona, Pelé and Zinedine Zidane.

“I know how many important icons have been part of this campaign,” says Nadal. “Being part of it is something I am very proud of—especially sharing it with Roger who has been my biggest rival and is now a close friend.”

Federer adds, “It’s a unique opportunity to be working on this campaign with Rafa. How we could be such great rivals and at the end of our careers be beside each other doing this campaign is very cool.” Tennis fans everywhere agree.

Watch the behind-the-scenes video shot of the new Louis Vuitton campaign.

You may also like.

Will Smith, Tom Brady And More Celebs Are Team Owners in a New Electric-Boat League

Will all that star power deliver?

At one point during the debut broadcast of the world’s first electric-boat racing circuit, an on-air host stands on a platform overlooking the water and pummels the camera with enthusiasm: “I hope you’re ready for a landmark moment that can change the future of water transportation. The nerves, the excitement, the energy, it’s electric!” Behind her, a few dozen people mill about, leaning on a rail, drinking coffee, staring at their phones. One turns to look at her as if he’d like to ask her to keep it down.

That singular image might best encapsulate the cognitive dissonance that permeates the new UIM E1 Series Championship.

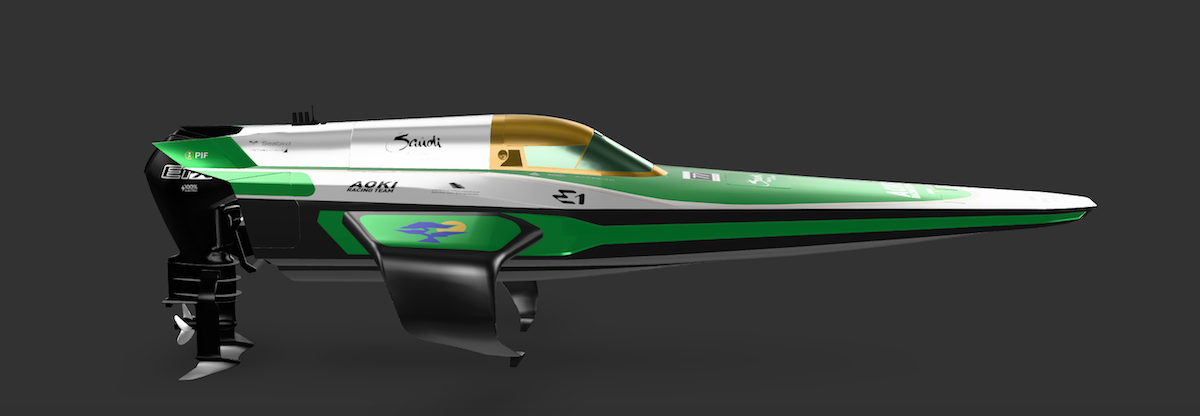

Take the boats. They look like remnants from a Star Wars movie, with long tapered noses leading to a glass-enclosed cockpit flanked on each side by a curving wing that acts as a hydrofoil, allowing the hulls fly over the surface while sending off huge sprays of white foam—but they’re nearly silent and, while they have explosive acceleration, they reach a top speed that wouldn’t even merit a ticket on an interstate.

E1 RACING

Then there are the team owners, a mélange of famous people who don’t necessarily bring to mind boats or racing. For that matter, they don’t really have anything to do with one another. Sorry, but it’s going to take more than a few brief hype videos and a recorded Zoom call in which the eight celebrities playfully talk trash before anyone believes the relationship between, say, NFL legend Tom Brady and pop singer Marc Anthony contains any real competitive juice.

There’s also the meeting of mission and money. The series defines itself as “committed to healing our coastal waters and ecosystems . . . through innovative clean technologies and aquatic regeneration.” But Saudi Arabia’s Public Investment Fund (PIF), which controls more than $USD700 billion in cash largely derived from oil production, holds a chunk of equity and occupies the top sponsorship space. (Disclosure: Saudi Arabia’s Research and Media Group has invested in Penske Media Corporation, Robb Report‘s parent company).

E1 RACING

None of it quite seems to go together, and yet, by many measures that first race, held on an inlet of the Red Sea in Jeddah on Feb. 3, was a success. Expect a ninth team headed by a famous Hollywood actor. The series will host seven more races this year, starting on the waterways of Venice on May 12.

All of which raises the question: Can this actually work?

“Boat racing has never really caught on,” admits Powerboat P1 CEO Azam Rangoonwala, who’s been in offshore racing for more than 20 years and is also a principal on E1’s Team Aoki. “We got involved with E1 because we see an opportunity to finally make that breakthrough happen.”

In 2020, Rodi Basso spent a fair part of the year trying to visualise life after the pandemic. Unlike many others, Basso wasn’t so much longing for the way things had been, as attempting to conjure what new world would emerge.

An aerospace engineer who’d transitioned into motorsports, he’d held jobs at Ferrari, Red Bull and McLaren Applied Technologies, but he’d recently stepped aside and moved to England in pursuit of some then-undetermined new challenge.

When the world shut down, he started running to stay fit and get out of the house, excursions on which he was often joined by Alejandro Agag, who lived nearby. Agag had founded Formula E and Extreme E, each a successful racing series featuring electric vehicles. The pair had met when Basso, through McLaren, developed an improved battery pack that allowed Formula E drivers to complete a race on a single charge.

E1 RACING

Basso, an Italian, and Agag, from Spain, debated the next big thing as they traversed the streets of London. Agag had invested in a start-up, Seabird, that was working on a foiling electric boat, and he asked Basso to help with the engineering. That simple request quickly morphed into a new idea—an electric boat racing series.

Perhaps no two individuals were better positioned to make it happen, and that night Basso created a deck summarizing the concept. The next day, he sent it to Agag who immediately signed on. The E1 World Championship Racing series was born amid expectations that it would become the next trending motorsports entity.

Within months they’d secured exclusive rights to stage electric boat races for 25 years through UIM, the international racing organization, and landed the PIF deal. Asked about the irony of Saudi oil money underwriting a series with a mission of “promoting sustainable energy use in marine sports,” and about assertions of greenwashing and sportswashing, Basso looked away from his computer screen.

Turning back, he offered a joke and then framed his answer in terms of investing strategies: “I focus on the day-to-day job of the people working at PIF who study markets and industries and place bets on what will bring the highest return. In that sense, it’s a privilege to be noticed and have that initial funding.”

Asked a similar question via email, Brady chooses not to respond, but otherwise replies: “This is a new competition and it has great growth potential, so it was a no-brainer for me to be involved with E1.”

Basso later adds another point: “PIF’s money allowed us to get going. It paid for the development of the boat and the series. Now we have to stand on our own as a functioning business.”

What will that look like?

Location, location, location. Part of the difficulty for boat racing has been the “where.” Contests usually took place offshore or on small—often remote—lakes that offered flat calm, neither of which are particularly spectator friendly.

In recent years, the Sail GP series has solved that problem with a global race circuit featuring smaller, more maneuverable versions of full America’s Cup boats slugging it out on metropolitan waterways, such as San Francisco Bay and Sydney Harbor. In contrast to traditional America’s Cup racing yachts, the smaller SailGP boats also reduce the costs of building, maintaining, outfitting, and shipping them to races around the world.

SAILGP

Besides that, the boat looks sleek, part spaceship, part waterbug, as it skitters above the surface. And while 50 knots (92.5 kmph) on a boat is fast—especially an open boat low to the water—it’s not an attention-getting number to the general public. Still, the Racebirds distinguish themselves with a burst of acceleration that’s visible when they compete.

The power comes from a Mercury outboard built specifically for the purpose, with input from Seabird. It has a booster that jacks the output from 100 kilowatts to 150 for 20 seconds per minute, adding to the notable jumps in speed and putting a focus on driver skill and strategy. Each team has two pilots—as they’re called—one male and one female, who alternate turns behind the wheel through a qualifying round, the semi-finals and finals.

“We’re now packaging the propulsion system to sell to other builders,” says Horne. “What drives me is the mission to electrify boats, so we want to partner with other companies out there and help build the infrastructure with fast charging that we’ll need.”

E1 RACING

The series’s green agenda goes beyond pushing the development of electric engines, high-output batteries and hydrofoils, which reduce drag in increase efficiency by lifting the boat’s hull out of the water. E1 intends to employ sustainable practices on-site at events—including the use of local vendors—and install and leave in place high-speed electric charging stations at each locale.

According to its website, organizers will collaborate on coastal restoration projects and education initiatives directed by chief scientist Carlos Duarte, an ocean ecology professor at King Abdullah University of Science and Technology.

“One of the barriers to ownership and sponsorship in powerboat racing has been the sustainability question,” says Rangoonwala of Powerboat P1. “E1 answers that question up front by building it into the mission.”

Whatever seeming contradictions arise from the use of PIF funds, the series has already had a real-world impact. Mercury Marine has incorporated much of the technology it developed for the Racebird engines into its Avator electric outboards. More than 12,000 Avators have been built in the last year. “Racebird was a good place for us to start,” David Foulkes, CEO of Brunswick Corp., Mercury’s parent, tells Robb Report. “It was a way to gain experience in a controlled environment, where the boats are centrally maintained.”

GETTY IMAGES

Basso calls Agag a “marketing genius” for the way he tapped into existing audiences for Formula E and Extreme E by luring well-known names from Formula 1 and extreme racing—and their social media followings—into the fold. It’s a proven approach, but one that would not work for E1. “Unfortunately, in powerboat racing, there are no star drivers or famous owners,” Basso says.

The alternative involved finding celebrities from other walks of life to invest in teams. “First, we approached Sergio Perez and evidently our presentation was done right because he joined, then Rafa Nadal signed up,” Basso says. “The rest came as a consequence of a sort of missing-out syndrome, which worked out nicely for us.”

The sell might have been easy, but the selections reflect the sort of calculated demographic cross-section that would make a pollster drool. Besides Brady, the white American hero of seven Super Bowls, Smith, the Black Hollywood superstar, Nadal, the internationally known Spanish tennis star, Anthony, the Grammy-winning musician with Latino roots, and Perez, a Formula 1 driver from Mexico, there’s Didier Drogba, a Black European soccer icon from Ivory Coast; Steve Aoki, a world-renown DJ of Japanese descent; Virat Kohli, a cricket star from India; and Marcelo Claure, a Bolivian tech entrepreneur.

All appear engaged at the outset, sitting for video interviews and promoting the series on social media. Four showed up for the opening race and Brady plans to be in Venice. “I’ve been involved in a few things since retiring but this racing series has been incredible,” Brady tells Robb Report. “I love competition and racing. Seeing the vision of the sport come to life has been very fun and fulfilling.”

Basso says he and Agag intentionally created a “business mechanism that would give owners skin in the game and keep them engaged.” The owners put up €2 million (about $2.15 million) to license a team. E1 owns the series and the boats and handles all the logistics, including transportation, for which they charge teams another €1 million. The buy-in, Basso says, will go up for Year 2, since three of the original eight license holders have already resold them at five times the initial investment.

To ensure those values keep rising, E1 plans to cap the series at 12 or 15 teams competing in 15 races, hopefully by Year 3, with five events in Asia, five in the Mid-East/Europe and five in the West, where potential venues include Miami, Mexico and Brazil.

To help control costs, the boats must run as they come out of the box, and though teams can hire as many engineers as they want back at headquarters, they can’t have more than seven crew members, including drivers, on the dock during races.

MERCURY MARINE

“They made some really smart decisions to limit costs at the outset,” says Ben King, one of of Team Brady’s co-principals. “The plan is to start modifying the boats in Year 3, which would mean greater outlays for teams, but by then, hopefully, the circuit will be well established.”

Teams can bring on sponsors outside those attached to the wider series, including everything from patches on pilot uniforms to on-the-boat decals to partnerships that showcase technology. Visibility shouldn’t be a problem. E1 has both linear and streaming deals with 120 broadcasters that range from Asia through India, MENA, Europe, and the Americas, where CBS owns the US television rights.

On the course at Jeddah, the four finalists line up for the rolling start of the final race, among them Team Brady. As the boats pass the marker buoy signaling the beginning of the first-ever E1 championship, three surge ahead while the Brady boat founders and wobbles forward, dropping to last.

In the previous heat, Brady’s Emma Kimiläinen finished third, meaning teammate Sam Coleman has to not just win the heat but make up the time deficit to claim the title. As the boats approach the first turn, Coleman mashes the booster and jolts forward, closing the gap and creating a three-boat bottleneck around the first buoy.

The scene turns chaotic as the boats speed through the curve within yards of each other and geysers of whitewater and churning wakes fill the space around them. Emerging into the straight, they jockey for the lead. “Racing these boats is super intense—insane,” says Coleman. “The trick is constantly managing the foil height. Too much power and the boat will drop and you’ll lose speed. The working window is so small, and while you don’t have engine noise, there’s feedback through cavitation and vibration that you have to learn to feel.”

E1 RACING

Most of the drivers have come from other disciplines, motorcycles, cars, even Jet Skis and WaveRunners. Coleman started in motocross, then teamed with his sister to become a world champion and two-time U.K. champ in P1 Powerboat. Whether it’s that experience or his feel for his craft, Coleman’s boat levels and rises high on its foils as it shoots to the front.

Through the next turns, Coleman’s lead builds, creating another bit of intrigue. The course layout consists of a small oval inside a larger one, something like a paperclip. Over a five-lap race, each driver must circumnavigate the inner oval four times and the outer once. As Coleman continues to pull away, the question of when to take the long lap rises.

E1 RACING

And while that gives the announcers something to talk about, it also highlights a shortcoming. The moments of close-quarters racing, the nuance of working the trim and booster and the strategic quirk of the long lap all make for good, engaging viewing. At the same time, the difficulty of keeping the boats running clean on the foils and the long lap spread the field, sapping most of the drama from the action. Those instances of intense, close-quarters racing are few and far between.

Ultimately, that’s what success will come down to: Will people understand the level of skill and strategy on display and will the competition hold up? A sustainability mission and a few 30-second hype videos from Tom Brady (whose team pulled through in Jeddah as the winner) provide a sense of purpose and attract eyeballs, but for people to continually show up and tune in—to pay up—the races themselves have to deliver.

Formula E and Extreme have made it work. Will E1? Ladies and gentlemen, start your very-quiet engines.

You may also like.

10 Fascinating Facts You Never Knew About Porsche

The automaker is a sports car standard-bearer with a long, impressive history in racing.

Porsche has long stood at the pinnacle of automotive achievement. The automaker has won the 24 Hours of Le Mans 19 times—more than any other competitor—and has successfully competed in everything from rally racing to Formula 1. The history of Porsche vehicle production is equally impressive, as the company rose from the rubble of World War II to become one of the most widely recognised luxury and performance brands in the world today. Let’s dive into the history of Porsche with 10 facts you might not have known about the German brand.

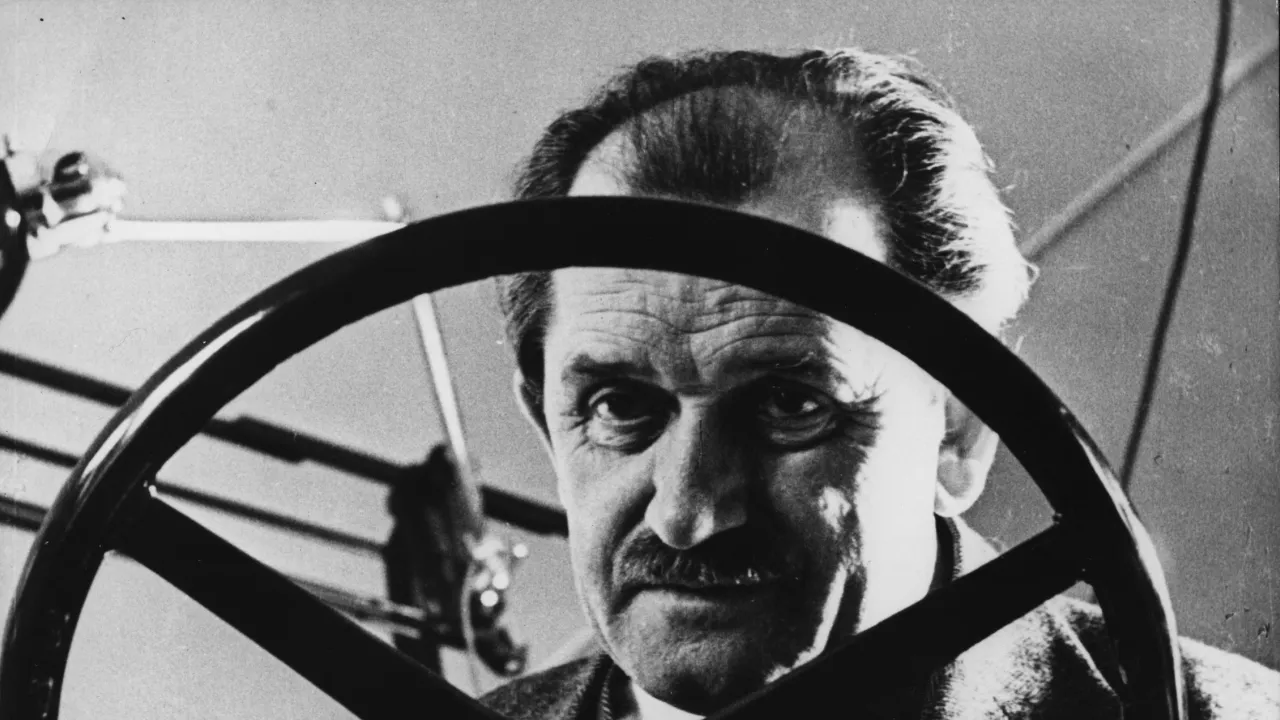

Porsche Was Founded by an Ex-Mercedes Engineer

Ferdinand Porsche was born in 1875 in what is now the Czech Republic. Despite the fact that he had little formal education, from an early age Porsche was recognised as a brilliant engineer. In 1901, Porsche built the world’s first gasoline-electric hybrid vehicle, a motorised carriage that used a Daimler internal-combustion engine to generate power for electric motors in the wheels. Soon, Porsche was hired as technical director of Stuttgart-based Daimler, where he worked on Mercedes race cars including the hugely successful Mercedes-Benz SSK.

Engineering Consultant

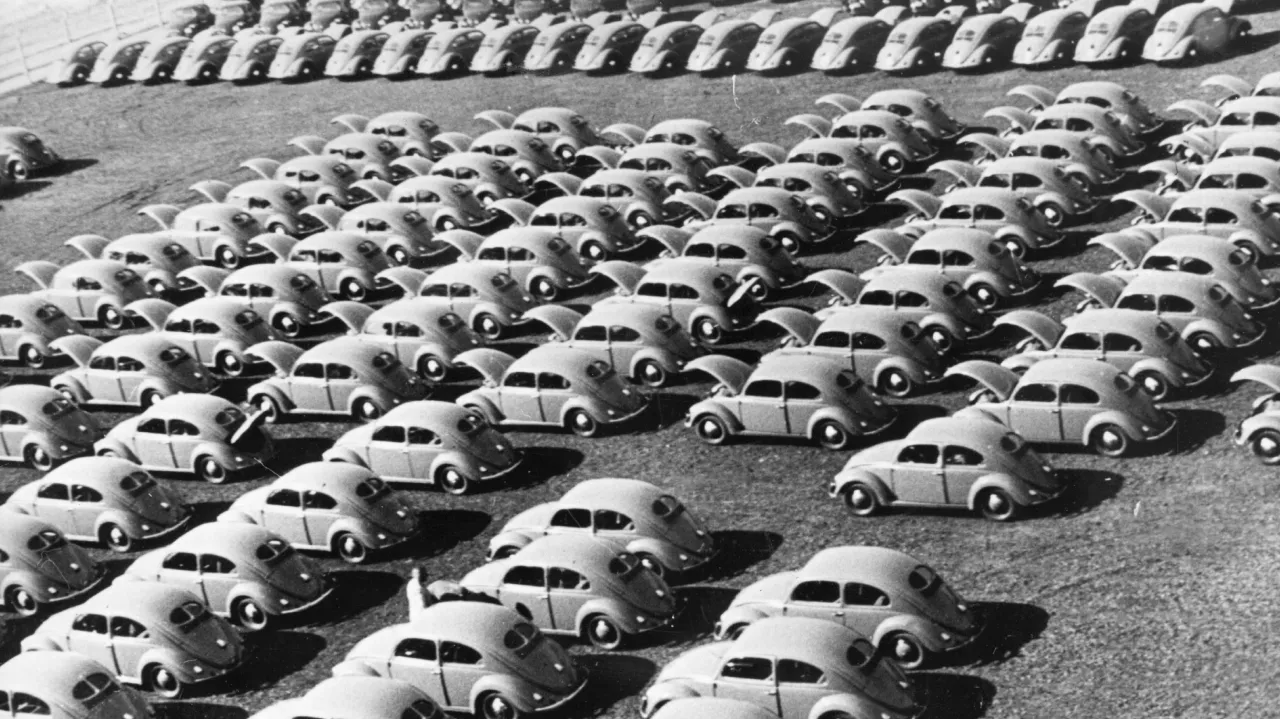

In 1931, Ferdinand Porsche launched the company that still bears his name today. It wasn’t a car-building operation: Dr. Ing h.c. F. Porsche GmbH was a consulting agency, supplying design and engineering expertise to various automakers. Soon after launching his company, Ferdinand Porsche received an assignment directly from German Chancellor Adolf Hitler: A project to build a simple, durable, affordable vehicle that could be purchased by everyday Germans, codenamed Volkswagen, or “people’s car.”

Porsche and World War II

Ferdinand Porsche unveiled the first Volkswagen prototype in 1935; in 1939, the Volkswagen factory began production, with Ferdinand Porsche appointed as an executive. As part of his work with the government of Nazi Germany, Porsche renounced his Czechoslovak citizenship, joined the Nazi Party, and became a member of the SS paramilitary group. Ferdinand Porsche contributed to the design and engineering of Nazi tanks and troop transport vehicles, and after World War II ended, he was arrested for war crimes including the use of forced labor, serving 20 months in prison in France.

Porsche Begins Building Its Own Cars

Following the end of World War II, Ferdinand Porsche’s son, Ferry, sought to build a sports car according to his father’s vision. In 1947, the first examples of the Porsche 356 were assembled in a small sawmill in Gmünd, Austria, where the Porsche family had moved operations to avoid Allied bombing. The 356 bore some resemblance to the Volkswagen, and like that vehicle, it used a rear-mounted four-cylinder engine along with some other VW components.

The 901, Or Rather, The 911

Porsche built several versions of the 356 until 1965, but by the end, the vehicle was badly out-of-date. Ferdinand Alexander Porsche, grandson of the company’s founder, designed a new rear-engine sports car, this time with an air-cooled six-cylinder engine. The company intended to call this model 901, which was the internal code-name for the project, but Peugeot owned the trademark on all three-digit model numbers with a zero in the middle, so the name was swiftly changed to 911.

The 917 Launches a Racing Dynasty

Porsche found racing success with the 356, 911, and various competition-only prototypes, but the automaker’s rise to motorsport dominance began with the 917. First shown publicly in 1969, the 917 was the brainchild of Ferdinand Piëch, a grandson of Ferdinand Porsche who would later go on to lead the entire Volkswagen Group. The race car used an air-cooled mid-mounted flat-12 engine, and it was so compact, the driver’s feet sat ahead of the front axle. After some early developmental troubles, the 917 became a dominant endurance racer, winning the 24 Hours of Daytona, the Monza 1,000km, the Spa-Francorchamps 1000 km, and the 24 Hours of Le Mans back-to-back in 1970 and 1971. The 917 was a monster, reliably cresting 230 mph at Le Mans in an era when the typical racing prototype couldn’t break 200, and it launched Porsche on a path to becoming the winningest manufacturer in Le Mans history.

911’s Near Death and Resurrection

The late 1970s were difficult for sports car companies, and in 1980 Porsche had its first year of financial losses. The 911 had gone without significant updates and was slated for cancellation, with the front-engine, V8-powered 928 intended to replace it. Newly-appointed CEO Peter Schutz, who was born in Germany but was raised in the U.S., realised that the impending death of the 911—considered the quintessential Porsche sports car—was contributing to low morale at Porsche. Schutz walked into the office of chief Porsche engineer Helmuth Bott, where a chart showed continued production of the 928 and 944, and the end of 911 production in 1981. In a scene that has become legend, Schultz took a marker from Bott’s desk, extending the 911’s line off the chart, onto the office wall, and out the door—signifying that the 911 would never be canceled. “Do we understand each other?” Schultz asked, and Bott nodded in the affirmative.

The World-Beating 959

In 1986, Porsche unveiled a supercar that shared the general shape of the 911, but was shockingly advanced in nearly every way: The 959. Developed to compete in Group B rally racing, the street-legal 959 had a twin-turbo engine making 326 kilowatts, Kevlar composite bodywork, wide-body fenders, and all-wheel drive. It soon became the fastest production car in the world, sprinting from zero to 96 in 3.7 seconds and reaching a 317 kmph top speed.

Amazingly, from 1963 to 1997, Porsche never undertook a full redesign of the 911. In 1998, a brand-new sports car emerged. Internally known as Type 996, the all-new 911 had a completely redesigned body shell and an all-new flat-six engine that, for the first time, was cooled by water rather than air. Early 996s shared their front bodywork and some interior panels with the more affordable mid-engine Boxster, causing some controversy among Porsche fans, but today the 996 is considered the model that saved the Porsche 911.

SUVs, Sedans, and the Future

In 2002, Porsche introduced the Cayenne, the automaker’s first sport-utility vehicle. A few years later, in 2009, the four-door Panamera luxury sedan was launched. Today, Porsche’s best-selling model is the Macan, a small SUV, with the Cayenne not far behind. The automaker also sells an all-electric sport sedan, the Taycan, and is moving toward the future with plans for hybrid and all-electric sports cars.

You may also like.

Sitting on the Dock of Balmain

Is The Dry Dock Sydney’s Hottest New Pub Renovation?

At its peak, in the late 1890s, Balmain had 55 pubs. They were noisy watering holes that serviced thirsty hordes after a day’s labour at the suburb’s harbourside coal mine and shipyards. Today, Balmain is dotted with charming workers’ cottages set behind picket fences and stolid corner pubs, which have been converted into restaurants and homes.

One such establishment, the Dry Dock on Cameron Street, has undergone a multi-million dollar renovation. As an original public house built in 1857, it remains fixed in a local backstreet and offers a porthole to the suburb’s blue-collar roots.

Locals can still bring their dogs into the front bar, or retreat to the lounge to sit next to a crackling log fire.

The renovation carried out by Studio Isgro and H&E Architects combines rustic touches—like the acid-etched sandstone exterior, exposed brickwork and beams —with elegant light fittings, an incredible sound system and tasteful art. “It has a transportive, escapist quality, where you could be anywhere, or right at home,” says interior designer Bianca Isgro of Studio Isgro, who spent two years on the overhaul. Her team designed a modern gastropub on the site after gutting and stripping the building, which had been neglected for years.

Founder and managing director James Ingram (ex-Solotel and Merivale) has assembled a warm, friendly service team that matches the pub’s character. He says his team has fought hard to preserve the pub’s long-standing connection to residents and to get the mix of old and new right.

“Balmain is home to so many devoted residents who are rightly proud of the suburb’s working-class roots,” says Ingram over a frothy beer in the warm-toned front bar.

“The Dry Dock has been designed to have that timeless feel that stands the test of time.”

The large open kitchen features an oyster bar and serves French-style fare, delicious sides, and hot desserts. The wine list is on point, with something in every price range and a friendly sommelier doing the rounds.

The kitchen is led by seasoned chef Ben Sitton, who previously rattled the pans at institutions including Felix, Uccello and Rockpool Bar & Grill. His kitchen faces a large dining room with unclothed tables, bentwood chairs, tumbled marble floors and exposed trusses that give it a contemporary feel.

The back of the room overlooks a walled garden, with a giant ghost gum at its centre and views of neighbouring residential fences.

Chef Sitton says his team relishes the opportunity to cook from an expansive modern European repertoire with quality produce. The robust flavours and textures are centred around the smoky quality that comes from Josper charcoal grills, wood-fired ovens, and the rotisserie.

You can order steak frites with charred baby carrots, or baked market fish with a cheesy, potato gratin.

The Peninsula Hospitality Group, the team behind Dry Dock, is now looking to expand its foothold in Balmain by opening at least one other venue.

Visit for the food, stay for the vibe.

The Dry Dock, Public House & Dining Room, 22 Cameron Street, Balmain, NSW 2041. P: 02 9555 1306; drydock.com.au