The intriguing history of digital time display

Digital watches in the 1970s may have been unprecedented, but mechanically actuated digital time displays can be traced back to pocket watches from the 1830s.

Related articles

Announcing the new Pulsar Time Computer in the early 1970s, the Hamilton Watch Company advertised its pioneering electronic digital watch as “the first completely new way to tell time in 500 years.” It became an instant icon. With a bright-red LED screen activated by a button, the Pulsar captured the imagination of a public that associated computers with hulking mainframes. The US$2,100 ($A2700) timepiece was soon spotted on the wrists of technophiles both real and imagined, from President Gerald Ford to James Bond.

But serious watch collectors knew that Hamilton’s boast was bogus. The Pulsar’s quartz-calibrated microcircuitry was unprecedented, but mechanically actuated digital time displays could be traced back to pocket watches from the 1830s, and mechanical digital wristwatches appeared as early as the 1920s. The first completely new way to tell time was in fact a novelty many times over. And each time — as Hamilton would learn at great expense when the market was swamped with cheap imitations — the trend passed in a flash.

We are now in the midst of another major comeback, not only with the onslaught of smart watches but also with the debut of innovative new mechanical timepieces such as F.P. Journe’s Vagabondage series and the A. Lange & Söhne Zeitwerk. Although history tells us to be wary, present-day watchmakers — at least those building movements with gears and springs — are familiar with their digital forebears as never before, and the past is actively informing new creations. After nearly two centuries of serial reinvention, digital may finally be emerging as an authentic tradition.

Part 1

The first major episode in the history of digital time indication foreshadows the Pulsar moment in both boldness and disappointment. It was 1881, and the International Watch Company was in need of a standout product after struggling for more than a decade to establish a market. Somehow the new owner, Johannes Rauschenbach-Schenk, learned of an invention by an Austrian father and son — both named Josef Pallweber — and decided that their mechanism could turn his business around.

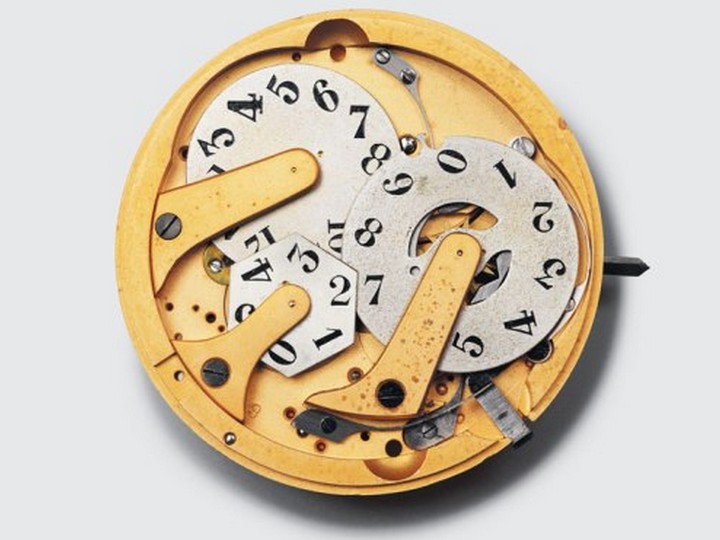

The invention was an under-dial module for digitally displaying the time on a pocket watch. Digits were painted on discs visible through windows on the watch face, with hours on the top and minutes on the bottom. Instead of turning gradually, the discs jumped every 60 seconds.

Although Abraham-Louis Breguet included jumping hour hands on some pocket watches in the early 19th century, and companies including Le Roy used numbered hour discs as early as 1830, the Pallweber system was the first to combine these ideas in a fully digital time indication. “It was a radical new way of showing the time in a time of technological change,” says IWC museum curator David Seyffer. “Mr. Rauschenbach had to have it, and he paid a hell of a lot of money for the patent.” The overall investment, including the cost of putting the watches into production, was more than US$10 ($A12.8) million in today’s money

Initially it looked like Rauschenbach had made a good bet. The timepiece was marketed as “the watch without hands,” and the IWC workshop couldn’t keep up with demand. But the mechanism proved more difficult to manufacture than Rauschenbach envisioned. The discs took considerable energy to turn because they were heavy and friction was required to hold them steady. At first the total running time for a Pallweber was less than 24 hours. Although dozens of changes in design and materials incrementally improved performance, manufacturing of the testy movements remained inefficient. Around 65 percent of each mechanism for the men’s Pallweber had to be crafted by hand. As a result, production of a Pallweber cost the company nearly twice the outlay for an ordinary movement. “They had huge plans to capture the whole U.S. market,” says Seyffer. With limited manufacturing capacity and high expenses, they never stood a chance.

Meanwhile other companies caught on to the digital trend and started to engineer their own mechanisms. These look-alikes took Rauschenbach by surprise, even more than the difficulty of putting Pallwebers into production. “He really believed that the Pallweber patent protected the digital way of showing the time,” says Seyffer. “Judges all over the world ruled that the patent only protected the mechanical means.”

Over the course of the 1880s, the market was flooded. By the tally of watch historian Alex Kuhn, more than 36 distinct movements were produced by 11 manufacturers, including Cortébert, Minerva, Wittnauer, and Lange.

During this period, operating in an increasingly crowded market, IWC was able to sell an estimated 20,000 timepieces. “But then suddenly in the 1890s, digital displays weren’t fashionable anymore,” says Seyffer. “People went back to the traditional way of telling the time.” IWC and other companies ceased production. A bitterly disappointed Rauschenbach turned his attention to precision chronometry, and the futuristic watch without hands was unceremoniously consigned to the past.

Part 2

In the early 20th century, people started to process time in a strikingly new way. Advocates of scientific management decreed that work hours should be strictly apportioned, and employees should be carefully monitored so that their labour could undergo cost analysis. Employees themselves facilitated this modern form of capitalism by punching in and out on mechanical time clocks. At least twice a day, they saw a digital time stamp on their punch cards.

Although the primary manufacturer of time clocks was the International Business Machine Corporation of New York, the development did not go unnoticed in Switzerland. In the early 1920s, Audemars Piguet began making wristwatches with a digital time indication. “The company was always interested in what was most modern,” says Audemars Piguet historian Michael Friedman. “And time clocks were the most prolific clocks of the era.”

So began another digital watch fad, apparently oblivious to the Pallweber mania of the 1880s. This time the jumping action was confined to the hours. (The minutes were also displayed on a disc, situated below the hours indication, but that disc rotated continuously.)

As Friedman observes, the system was essentially equivalent to a traditional calendar mechanism. “It’s a matter of under-dial work, of cadrature, which was very well established in Vallée de Joux watchmaking,” he says. Unlike the Pallweber movement, which was a genuine technological breakthrough, Friedman views the Audemars Piguet digital display as “a design-driven innovation.”

The modern design aesthetic was applied to every element of this timepiece. Rectangular in form, Audemars Piguet jumping-hour watches were distinguished by bold Arabic numerals and angular Art Deco cases. They looked like machines. That was no accident, observes Friedman: “Watches are not siloed objects, but are part of the culture.” The reciprocal relationship between the era and the digital time indication made digital watches enormously popular up until the Great Depression. (In addition to Audemars Piguet, Deco-styled jump-hour watches were produced by companies ranging from Rolex to Elly.) And then, as the stock market crashed, they vanished once again.

Part 3

As an apprentice to the famous clockmaker Johann Gutkaes in the early 1840s, Ferdinand A. Lange worked on an unusual clock for Dresden’s opera house. The clock showed the time digitally, with jumping hour and 5-minute indications arranged horizontally, foreshadowing the horizontal display of time made commonplace by the Hamilton Pulsar and its electronic-digital successors.

More than a century and a half after the Semper Opera House opened, A. Lange & Söhne decided to develop a digital wristwatch inspired by Gutkaes’s clock. Unlike the modestly sized two-tier digital displays of antique watches, the company sought a horizontal display with very large digits. The watchmakers were well aware of the challenges they faced: the problems of Pallwebers writ large. “Instantaneously moving big discs every minute requires a lot more energy than moving hands,” says Lange director of product development Anthony de Haas. A powerful spring is needed. “But if your mainspring is too strong,” he explains, “you can’t power an escapement with it.”

In search of a solution, de Haas researched the past, in particular Lange’s own legacy as a manufacturer of digital pocket watches. Lange technicians made computer simulations of new movements based on the Pallweber and also the Dürrstein system, which was the mechanism Lange used in the 1880s to circumvent IWC’s Pallweber patent. The Dürrstein showed promise, says de Haas, as it had the advantage of running the digital display on a separate gear train. But he found that it consumed too much power. Instead he opted to ditch digital precedents completely, learning from their inadequacies.

The mechanism he developed adapts the classic remontoir d’égalité. It uses a mainspring twice as powerful as normal, but the power is conveyed to a secondary spring every minute, as the discs jump. The secondary spring powers the escapement for the next 60 seconds. “You not only have a watch that indicates time digitally,” de Haas says, “but it’s also a very precise watch because it has constant force.” Released in 2009, the Zeitwerk has subsequently undergone numerous permutations — including a decimal chiming mechanism — further exploiting the remontoir’s energy distribution.

Concurrent with Lange’s developments, other contemporary watchmakers have revisited the history of digital watchmaking, resulting in other innovations. One of the most unconventional is F.P. Journe.

Since 2004, Journe has systematically explored combinations of digital and analog time display with his Vagabondage series, taking inspiration (and forewarning) from digital pocket watches in his personal collection. “The mechanisms of antique pocket watches with digital indications are really catastrophic mechanically,” he says. “Much precaution is needed to avoid the numerous traps.” He ultimately overcame the problems of accuracy, and the related challenge of providing sufficient power, by developing his own remontoir d’égalité.

With the Vagabondage II of 2010, the mechanism imparted constant force every minute, equivalent to the Zeitwerk. This year Journe used the same system to release energy at 60 times that rate, one revolution per second, creating the world’s first mechanical timepiece with digital seconds.

The range of digital displays and mechanisms that have appeared over the past decade is unprecedented, with recent novelties released by companies including Hublot, Chanel, Hautlence, and MB&F. Michael Friedman is not surprised. “We’re moving deeper and deeper into the digital age, and these analog watches that flirt with digital aesthetics are appealing to contemporary collectors,” he says. “You know something is gear driven, yet the display is incredibly futuristic and contemporary. That’s an exciting dichotomy.”

Over at Lange, de Haas holds a similar opinion. He’s observed that the Zeitwerk has been especially popular with the business leaders of Silicon Valley and technophiles more broadly. “The younger generation is accustomed to digital displays,” he says. “It’s how they see time.”

Ironically, the Hamilton Pulsar may have made possible the transition of digital-mechanical timekeeping from trend to tradition, by priming the revolution that made quartz-based digital time indication ubiquitous. The Pulsar was not the first completely new way to tell time in 500 years — but the Pulsar age was the first to free mechanical watchmakers to pursue watchmaking for its own sake.

Subscribe to the Newsletter

Recommended for you

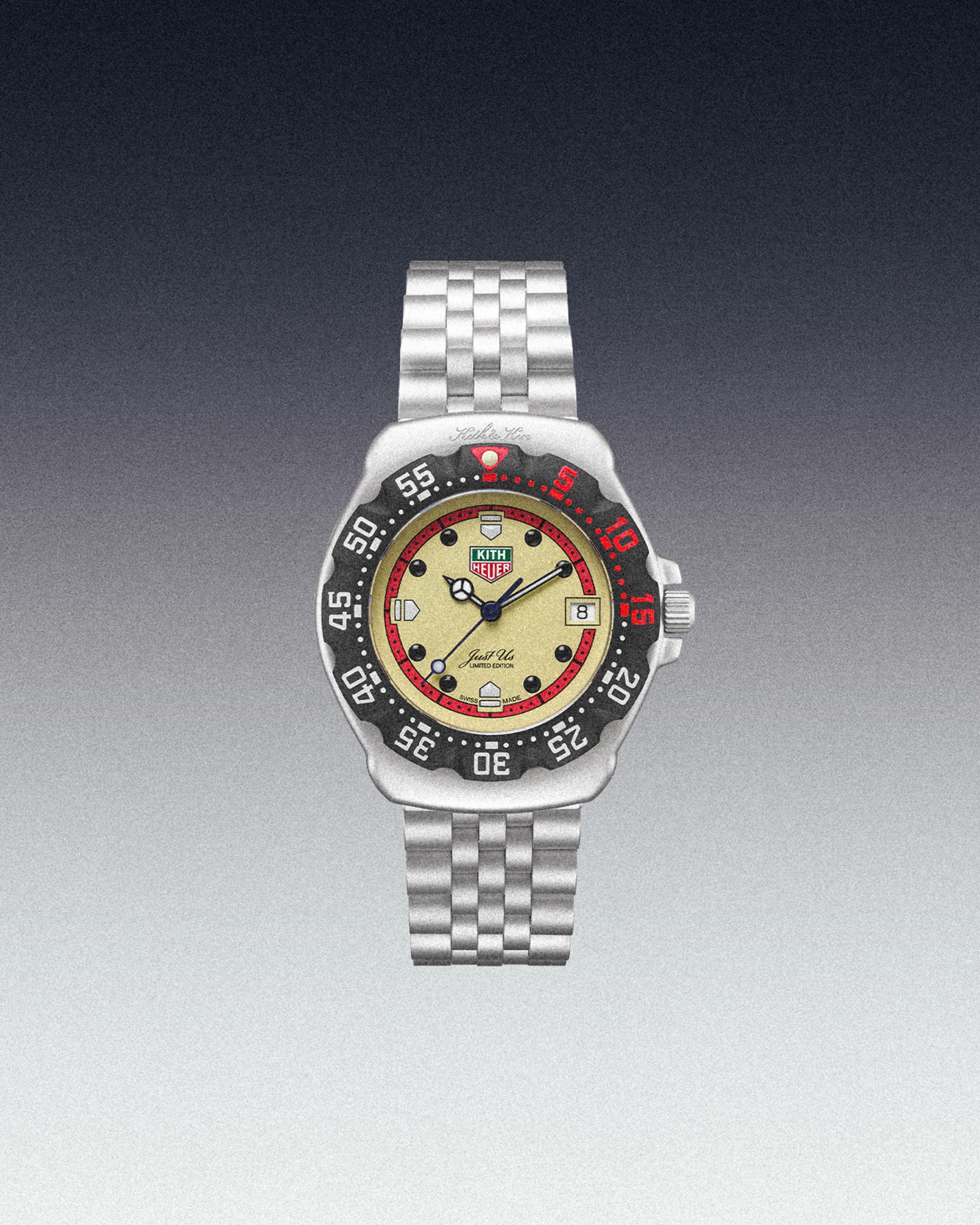

Watch of the Week: TAG Heuer Formula 1 | Kith

The legendary sports watch returns, but with an unexpected twist.

By Josh Bozin

May 2, 2024

Omega Reveals a New Speedmaster Ahead of the Paris 2024 Olympics

Your first look at the new Speedmaster Chronoscope, designed in the colour theme of the Paris Olympics.

By Josh Bozin

April 26, 2024

You may also like.

You may also like.

Best fo Europe: Six Senses, Switzerland

Mend in the mountains at Crans-Montana.

Wellness pioneer Six Senses made a name for itself with tranquil, mostly tropical destinations. Now, its first alpine hotel recreates that signature mix of sustainable luxury and innovative spa therapeutics in a world-class ski setting.

The ski-in, ski-out location above the gondola of one of Switzerland’s largest winter sports resorts allows guests to schuss from the top of the Plaine Morte glacier to the hotel’s piste-side lounge, where they can swap ski gear for slippers, then head straight to the spa’s bio-hack recovery area to recharge with compression boots, binaural beats and an herb-spiked mocktail. In summer, the region is a golf and hiking hub.

The vibe offers a contemporary take on chalet style. The 78 rooms and suites are decorated in local larch and oak, and all have terraces or balconies with alpine views over the likes of the Matterhorn and Mont Blanc. With four different saunas, a sensory flotation pod, two pools

and a whimsical relaxation area complete with 15,000 hanging “icicles” and views of a birch forest, the spa at Six Senses Crans-Montana makes après ski an afterthought.

You can even sidestep the cheese-heavy cuisine of this region in favour of hot pots and sushi at the property’s Japanese restaurant, Byakko. Doubles from around $1,205; Sixsenses.com

You may also like.

Best of Europe: Grand Hotel Des Étrangers

Fall for a Baroque beauty in Syracuse, Italy.

Sicily has seen a White Lotus–fuelled surge in bookings for this summer—a pop-culture fillip to fill up its grandes dames hotels. Skip the gawping crowds at the headline-grabbers, though, and opt instead for an insider-ish alternative: the Grand Hotel des Étrangers, which reopened last summer after a gut renovation.

It sits on the seafront on the tiny island of Ortigia in Syracuse, all cobbled streets and grand buildings, like a Baroque time capsule on Sicily’s southeastern coast.

Survey the entire streetscape here from the all-day rooftop bar-restaurant, Clou, where the fusion menu is a shorthand of Sicily’s pan-Mediterranean history; try the spaghetti with bottarga and wild fennel or the sea bass crusted in anchovies. Idle on the terrace alfresco with a snifter of avola, the rum made nearby.

As for the rooms, they’ve been renovated with Art Deco–inflected interiors—think plenty of parquet and marble—but the main asset is their aspect: the best of them have private balconies and a palm tree-fringed view out over the Ionian Sea. Doubles from around $665; desetranger.com

You may also like.

Watch of the Week: TAG Heuer Formula 1 | Kith

The legendary sports watch returns, but with an unexpected twist.

Over the last few years, watch pundits have predicted the return of the eccentric TAG Heuer Formula 1, in some shape or form. It was all but confirmed when TAG Heuer’s heritage director, Nicholas Biebuyck, teased a slew of vintage models on his Instagram account in the aftermath of last year’s Watches & Wonders 2023 in Geneva. And when speaking with Frédéric Arnault at last year’s trade fair, the former CEO asked me directly if the brand were to relaunch its legacy Formula 1 collection, loved by collectors globally, how should they go about it?

My answer to the baited entreaty definitely didn’t mention a collaboration with Ronnie Fieg of Kith, one of the world’s biggest streetwear fashion labels. Still, here we are: the TAG Heuer Formula 1 is officially back and as colourful as ever.

As the watch industry enters its hype era—in recent years, we’ve seen MoonSwatches, Scuba Fifty Fathoms, and John Mayer G-Shocks—the new Formula 1 x Kith collaboration might be the coolest yet.

Here’s the lowdown: overnight, TAG Heuer, together with Kith, took to socials to unveil a special, limited-edition collection of Formula 1 timepieces, inspired by the original collection from the 1980s. There are 10 new watches, all limited, with some designed on a stainless steel bracelet and some on an upgraded rubber strap; both options nod to the originals.

Seven are exclusive to Kith and its global stores (New York, Los Angeles, Miami, Hawaii, Tokyo, Toronto, and Paris, to be specific), and are made in an abundance of colours. Two are exclusive to TAG Heuer; and one is “shared” between TAG Heuer and Kith—this is a highlight of the collection, in our opinion. A faithful play on the original composite quartz watch from 1986, this model, limited to just 1,350 pieces globally, features the classic black bezel with red accents, a stainless steel bracelet, and that creamy eggshell dial, in all of its vintage-inspired glory. There’s no doubt that this particular model will present as pure nostalgia for those old enough to remember when the original TAG Heuer Formula 1 made its debut.

Of course, throughout the collection, Fieg’s design cues are punctuated: the “TAG” is replaced with “Kith,” forming a contentious new brand name for this specific release, as well as Kith’s slogan, “Just Us.”

Collectors and purists alike will appreciate the dedication to the original Formula 1 collection: features like the 35mm Arnite cases—sourced from the original 80s-era supplier—the form hour hand, a triangle with a dot inside at 12 o’clock, indices that alternate every quarter between shields and dots, and a contrasting minuterie, are all welcomed design specs that make this collaboration so great.

Every TAG Heuer Formula 1 | Kith timepiece will be presented in an eye-catching box that complements the fun and colour theme of Formula 1 but drives home the premium status of this collaboration. On that note, at $2,200 a piece, this isn’t exactly an approachable quartz watch but reflects the exclusive nature of Fieg’s Kith brand and the pieces he designs (largely limited-edition).

So, what do we think? It’s important not to understate the significance of the arrival of the TAG Heuer Formula 1 in 1986, in what would prove integral in setting up the brand for success throughout the 90’s—it was the very first watch collection to have “TAG Heuer” branding, after all—but also in helping to establish a new generation of watch consumer. Like Fieg, many millennial enthusiasts will recall their sentimental ties with the Formula 1, often their first timepiece in their horological journey.

This is as faithful of a reissue as we’ll get from TAG Heuer right now, and budding watch fans should be pleased with the result. To TAG Heuer’s credit, a great deal of research has gone into perfecting and replicating this iconic collection’s proportions, materials, and aesthetic for the modern-day consumer. Sure, it would have been nice to see a full lume dial, a distinguishing feature on some of the original pieces—why this wasn’t done is lost on me—and perhaps a more approachable price point, but there’s no doubt these will become an instant hit in the days to come.

—

The TAG Heuer Formula 1 | Kith collection will be available on Friday, May 3rd, exclusively in-store at select TAG Heuer and Kith locations in Miami, and available starting Monday, May 6th, at select TAG Heuer boutiques, all Kith shops, and online at Kith.com. To see the full collection, visit tagheuer.com

You may also like.

06/05/2024

30/04/2024

06/05/2024

8 Fascinating Facts You Didn’t Know About Aston Martin

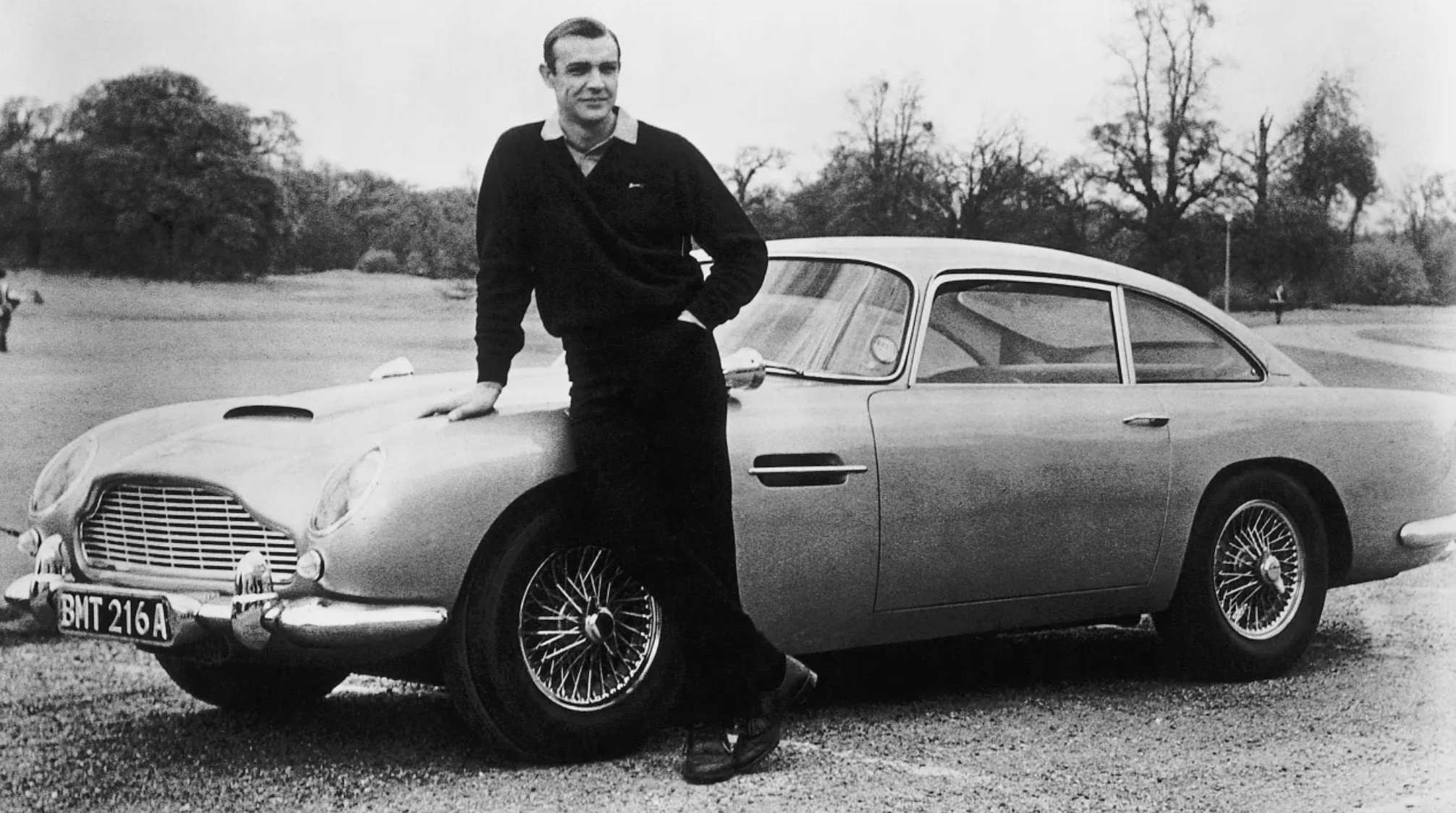

The British sports car company is most famous as the vehicle of choice for James Bond, but Aston Martin has an interesting history beyond 007.

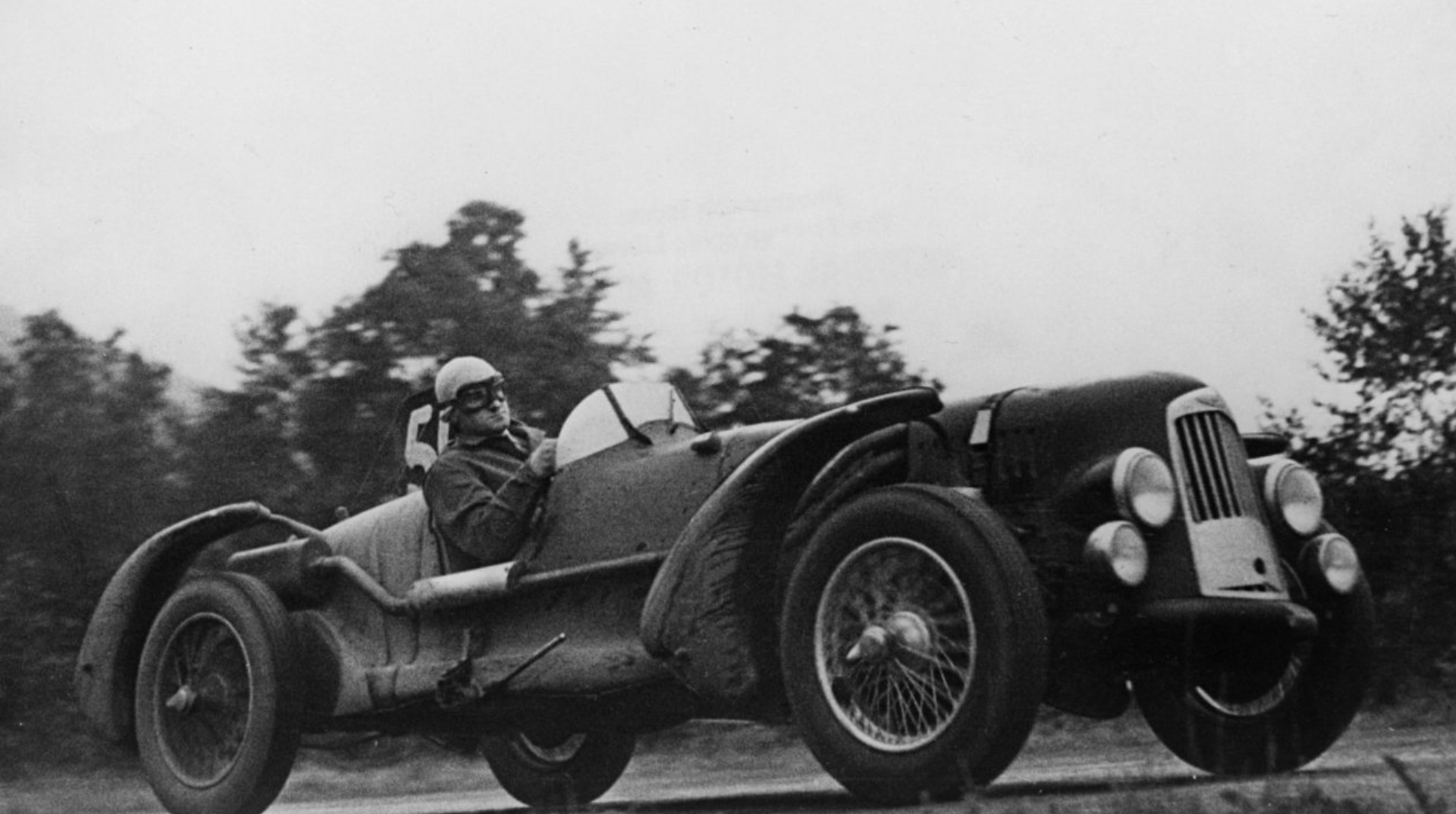

Aston Martin will forever be associated with James Bond, ever since everyone’s favourite spy took delivery of his signature silver DB5 in the 1964 film Goldfinger. But there’s a lot more to the history of this famed British sports car brand beyond its association with the fictional British Secret Service agent.

Let’s dive into the long and colourful history of Aston Martin.

You may also like.

What Venice’s New Tourist Tax Means for Your Next Trip

The Italian city will now charge visitors an entry fee during peak season.

Visiting the Floating City just got a bit more expensive.

Venice is officially the first metropolis in the world to start implementing a day-trip fee in an effort to help the Italian hot spot combat overtourism during peak season, The Associated Press reported. The new program, which went into effect, requires travellers to cough up roughly €5 (about $AUD8.50) per person before they can explore the city’s canals and historic sites. Back in January, Venice also announced that starting in June, it would cap the size of tourist groups to 25 people and prohibit loudspeakers in the city centre and the islands of Murano, Burano, and Torcello.

“We need to find a new balance between the tourists and residents,’ Simone Venturini, the city’s top tourism official, told AP News. “We need to safeguard the spaces of the residents, of course, and we need to discourage the arrival of day-trippers on some particular days.”

During this trial phase, the fee only applies to the 29 days deemed the busiest—between April 25 and July 14—and tickets will remain valid from 8:30 am to 4 pm. Visitors under 14 years of age will be allowed in free of charge in addition to guests with hotel reservations. However, the latter must apply online beforehand to request an exemption. Day-trippers can also pre-pay for tickets online via the city’s official tourism site or snap them up in person at the Santa Lucia train station.

“With courage and great humility, we are introducing this system because we want to give a future to Venice and leave this heritage of humanity to future generations,” Venice Mayor Luigi Brugnaro said in a statement on X (formerly known as Twitter) regarding the city’s much-talked-about entry fee.

Despite the mayor’s backing, it’s apparent that residents weren’t totally pleased with the program. The regulation led to protests and riots outside of the train station, The Independent reported. “We are against this measure because it will do nothing to stop overtourism,” resident Cristina Romieri told the outlet. “Moreover, it is such a complex regulation with so many exceptions that it will also be difficult to enforce it.”

While Venice is the first city to carry out the new day-tripper fee, several other European locales have introduced or raised tourist taxes to fend off large crowds and boost the local economy. Most recently, Barcelona increased its city-wide tourist tax. Similarly, you’ll have to pay an extra “climate crisis resilience” tax if you plan on visiting Greece that will fund the country’s disaster recovery projects.