Five Luxurious Additions To The Games Room

Old fashioned fun and elevated craftsmanship for the remaining indoor times ahead. And because winter is starting to settle in.

Related articles

Enforced quarantine’s meant a string of completed Netflix titles and a chance to finally nail sous-vide cooking. And while we look to be released from more stringent regulations, there’s still some old-fashioned fun to be had at home.

Here, five luxe games to see you through.

Louis Vuitton: Foosball Table

The European gameroom staple that is foosball has been elevated by Louis Vuitton. Hand crafted and made to order, this lavish table set receives the LV treatment via cowhide leather handles and panels, showcasing the iconic monogrammed pattern, alongside counting coins modelled after the monogram flower. Available in a range of colours and designs.

Approx. $150,000; louisvuitton.com

247 Billiards: Porsche Design Billiards Table

Porsche Design Studio raises the stakes in this collaboration with 247 Billiards. A unique and minimal table design that presents as if cut from a single piece, its made of stainless steel and aluminium with fine fabrics inclusive of calf-leather. It’s also highly customisable – grab a preferred tone or whatever best works with the interior scheme.

Approx. $45,000; 247billiards.com

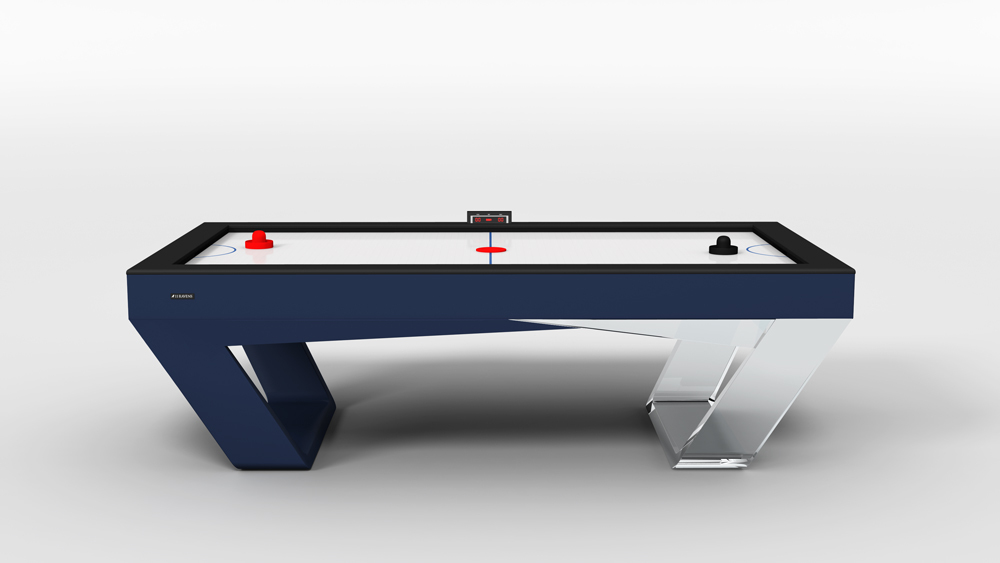

11 Ravens: Avettore Air-Hockey

The USA based 11 Ravens has a reputation for creating outrageously luxurious games, extending across pool, ping-pong and recently, air-hockey tables. The pictured ‘Avettore’ takes its cues from aeronautics and boasts a high-pressure laminate playing field and a commercial blower that flows 6-cubic-metres of air per minute to keep the puck gliding. Not a fan of the traditional blue? Then choose the appropriate lacquer, stain, veneer or laminate to suit your tastes.

Approx. $38,700; 11ravens.com

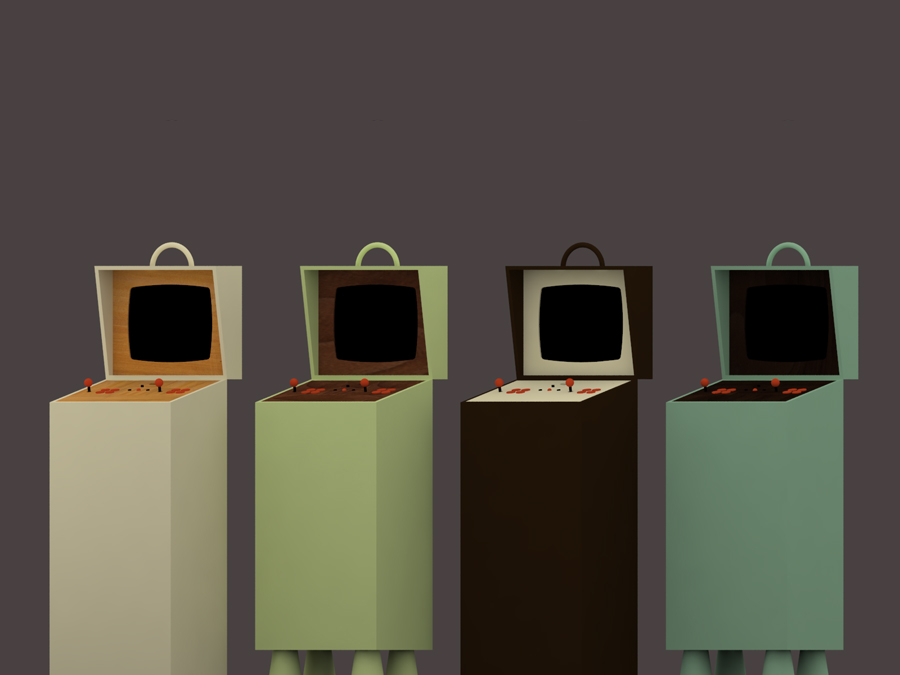

Love Hultén: Pixelkabinett 42 – Retro Arcade Machine

A blast from the past doesn’t have to feel like it. Love Hultén, a Swedish craftsman, has combined his love of old-world gaming and arcades and fashioned it into luxe casings that won’t be eyesores in a home. Take the Pixelkabinett 42, made to order in the colour of your choosing, the standard version landing with a chosen classic arcade-style board and modern computer emulating favourite games of yesteryear.

Approx: $6,500; lovehulten.com

Sean Woolsey: Ping Pong Table

The solid black walnut top on a steel base brings this addictive game to new heights. The sugar maple centre line adds symmetry and keeps play fair, while the solid walnut legs are sleeved for adjustment – ensuring an even play surface. The net is made from powder-coated steel and comes with two custom made walnut paddles, three-star balls and a wall mount to keep it decluttered.

Approx. $15,200; seanwoolsey.com

Subscribe to the Newsletter

Recommended for you

From Electric Surfboards to Biodegradable Golf Balls: 8 Eco-Conscious Yacht Toys for Green and Clean Fun

Just add water and forget the eco-guilt.

By Gemma Harris

October 18, 2023

Life Is But A Game And These Maisons Are Making The Chicest Ones

Not for sore losers and board flippers, these board games and outdoor amusements are a far cry from the sets of your childhood.

August 9, 2023

You may also like.

17/04/2024

18/04/2024

You may also like.

Polar Opposites

A journey north to one of the harshest, remotest spots on Earth couldn’t be more luxurious.

A century ago, an expedition to the North Pole involved dog sleds and explorers in heavy, fur-lined clothes, windburned and famished after weeks of trudging across ice floes, finally planting their nations’ flags in the barren landscape. These days, if you’re a tourist, the only way to reach 90 degrees north latitude, the geographic North Pole, is aboard Le Commandant Charcot, a six-star hotel mated to a massive, 150-metre ice-breaking hull.

My wife, Cathy, and I are among the first group of tourists aboard Ponant’s new expedition icebreaker, the world’s only Polar Class 2–rated cruise ship (of seven levels of ice vessel, second only to research and military vessels in ability to manoeuvre in Arctic conditions). Our arrival on July 14 couldn’t be more different from explorer Robert Peary’s on April 6, 1909. On that date, he reported, he staked a small American flag—sewed by his wife—into the Pole, joined by four Inuits and his assistant, Matthew Henson, a Black explorer from Maine who was with Peary on his two previous Arctic expeditions. (Peary’s claim of being first to the Pole was quickly disputed by another American, Frederick Cook, who insisted he’d spent two days there a year earlier. Scholars now view both claims with skepticism.)

Our 300-plus party’s landing, on Bastille Day, features the captain of the French ship driving around in an all-terrain vehicle with massive wheels and an enormous tricolour flag on the back, guests dressed in stylish orange parkas celebrating on the ice, and La Marseillaise, France’s national anthem, blaring from loudspeakers. After an hour of taking selfies and building snow igloos in the icescape, with temperatures in the relatively balmy low 30s, we head back into our heated sanctuary for mulled wine and freshly baked croissants. Mission accomplished. Flags planted. Now, lunch.

As a kid, I was fascinated by stories of adventurers trying to reach the North Pole without any means of rescue. In the 19th century, most of their attempts ended in disaster—ships getting trapped in the ice, a hydrogen balloon crashing, even cannibalism. It wasn’t until Cook and Peary reportedly set foot there that the race to the North Pole was really on. Norwegian Roald Amundsen, the first to reach the South Pole, in 1911, is credited with being the first to document a trip over the North Pole, which he did in 1926 in the airship Norge. In 1977, the nuclear-powered icebreaker Arktika became the first surface vessel to make it to the North Pole. Since then, only 18 other ships have completed the voyage.

Visiting the North Pole seemed about as likely for me as walking on the Moon. It wasn’t even on my bucket list. Then came Le Commandant Charcot, which was named after France’s most beloved polar explorer and reportedly cost about US$430 million (around $655 million) to build. The irony of visiting one of the planet’s most remote and inhospitable points while travelling in the lap of luxury doesn’t escape me or anyone else I speak with on the voyage. Danie Ferreira, from Cape Town, South Africa, describes it as “an ensemble of contradictions bordering on the absurd”. Ferreira, who is on board with his wife, Suzette, is a veteran of early-explorer-style high-Arctic journeys, months-long treks involving dog sleds and real toil and suffering. He booked this trip to obtain an official North Pole stamp for an upcoming two-volume collection of his photographs, Out in the Cold, documenting his polar adventures. “Reserving the cabin felt like a betrayal of my expeditionary philosophy,” he says with a laugh.

Then, like the rest of us, he embraces the contradictions. “This is like the first time I saw the raw artistry of Cirque du Soleil,” he explains. “Everything is beyond my wildest expectations, unrelatable to anything I’ve experienced.”

The 17-day itinerary launches from the Norwegian settlement of Longyearbyen, Svalbard, the northernmost town in the Arctic Circle, and heads 1,186 nautical miles to the North Pole, then back again. As a floating hotel, the vessel is exceptional: 123 balconied staterooms and suites, the most expensive among them duplexes with butler service (prices range from around $58,000 to $136,000 per person, double occupancy); a spa with a sauna, massage therapists, and aestheticians; a gym and heated indoor pool. The boat weighs more than 35,000 tons, enabling it to break ice floes like “a chocolate bar into little pieces, rather than slice through them”, according to Captain Patrick Marchesseau. Six-metre-wide stainless-steel propellers, he adds, were designed to “chew ice like a blender”.

Marchesseau, a tall, lanky, 40-ish mariner from Brittany, impeccable in his navy uniform but rocking royal-blue boat shoes, proves to be a charming host. Never short of a good quip, he’s one of three experienced ice captains who alternate at the helm of Charcot throughout the year. He began piloting Ponant ships through drifting ice floes in Antarctica in 2009, when he took the helm of Le Diamant, Ponant’s first expedition vessel. “An epic introduction,” Marchesseau calls those early voyages, but the isolated, icebound North Pole aboard a larger, more complicated vessel is potentially an even thornier challenge. “We’ll first sail east where the ice is less concentrated and then enter the pack at 81 degrees,” he tells a lecture hall filled with passengers on day one. “We don’t plan to stop until we get to the North Pole.”

Around us, the majority of the other 101 guests are older French couples; there are also a few extended families, some other Europeans, mostly German and Dutch, as well as 10 Americans. Among the supporting cast are six research scientists and 221 staff, including 18 naturalist guides from a variety of countries.

The first six days are more about the journey than the destination. Cathy and I settle into our comfortable stateroom, enjoy the ocean views from our balcony, make friends with other guests and naturalists, frequent the spa, and indulge in the contemporary French cuisine at Nuna, which is often jarred by ice passing under the hull, as well as at the more casual Sila (Inuit for “sky”). There are the usual cruise events: the officers’ gala, wine pairings, daily French pastries, Broadway-style shows, opera singers and concert pianists. Initially, I worry about “Groundhog Day” setting in, but once we hit patchy ice floes on day two, it’s clear that the polar party is on. The next day, we’re ensconced in the ice pack.

Veterans of Arctic journeys immediately feel at home. Ferreira, often found on the observation deck 15 metres above the ice with his long-lensed cameras, is in his element snapping different patterns and colours of the frozen landscape. “It feels like combining low-level flying with an out-of-body experience,” he says. “Whenever the hull shudders against the ice, I have a reality check.”

“I came back because I love this ice,” adds American Gin Millsap, who with her husband, Jim, visited the North Pole in 2015 aboard the Russian nuclear icebreaker Fifty Years of Victory, which for obvious reasons is no longer a viable option for Americans and many Europeans. “I love the peace, beauty and calmness.”

It is easy to bliss out on the endless barren vistas, constantly morphing into new shapes, contours and shades of white as the weather moves from bright sunshine to howling snowstorms—sometimes within the course of a few hours. I spend a lot of time on the cold, windswept bow, looking at the snow patterns, ridges and rivers flowing within the pale landscape as the boat crunches through the ice. It feels like being in a black-and-white movie, with no colours except the turquoise bottoms of ice blocks overturned by the boat. Beautiful, lonely, mesmerising.

Rather than a solid landmass, the Arctic ice pack is actually millions of square kilometres of ice floes, slowly pushed around by wind and currents. The size varies according to season: this past winter, the ice was at its fifth-lowest level on record, encompassing 14.6 million square kilometres, while during our cruise it was 4.7 million square kilometres, the 10th-lowest summer number on record. There are myriad ice types—young ice, pancake ice, ice cake, brash ice, fast ice—but the two that our ice pilot, Geir-Martin Leinebø, cares about are first-year ice and old ice. The thinness of the former provides the ideal route to the Pole, while the denseness of the aged variety can result in three-to-eight-metre-high ridges that are potentially impassable. Leinebø is no novice: in his day job, he’s the captain of Norway’s naval icebreaker, KV Svalbard, the first Norwegian vessel to reach the North Pole, in 2019.

It’s not a matter of just pointing the boat due north and firing up the engine. Leinebø zigzags through the floes. A morning satellite feed and special software aid in determining the best route; the ship’s helicopter sometimes scouts 65 or so kilometres ahead, and there’s a sonar called the Sea Ice Monitoring System (SIMS). But mostly Leinebø uses his eyes. “You look for the weakest parts of the ice—you avoid the ridges because that means thickness and instead look for water,” he says. “If the ‘water sky’ in the distance is dark, it’s reflecting water like a mirror, so you head in that direction.”

Everyone on the bridge is surprised by the lack of multi-year ice, but with more than a hint of disquietude. Though we don’t have to ram our way through frozen ridges, the advance of climate change couldn’t be more apparent. Environmentalists call the Arctic ice sheet the canary in the coal mine of the planet’s climate change for good reason: it is happening here first. “It’s not right,” mutters Leinebø. “There’s just too much open water for July. Really scary.”

The Arctic ice sheet has shrunk to about half its 1985 size, and as both mariners and scientists on board note, the quality of the ice is deteriorating. “It’s happening faster than our models predicted,” says Marisol Maddox, senior arctic analyst at the Polar Institute of the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars. “We’re seeing major events like Greenland’s ice sheet melting and sliding into the ocean—that wasn’t forecasted until 2070.” The consensus had been that the Arctic would be ice-free by 2050, but many scientists now expect that day to come in the 2030s.

That deterioration, it turns out, is why the three teams of scientists are on the voyage—two studying the ice and the other assessing climate change’s impact on plankton. As part of its commitment to sustainability, Ponant has designed two research labs—one wet and one dry—on a lower deck. “We took the advice of many scientists for equipping these labs,” says Hugues Decamus, Charcot’s chief engineer, clearly proud of the nearly US$12 million facilities.

The combined size of the labs, along with a sonar room, a dedicated server for the scientists, and a meteorological station on the vessel’s top deck, totals 130 square metres—space that could have been used for revenue generation. Ponant also has two staterooms reserved for scientists on each voyage and provides grants for travel expenses. The line doesn’t cherrypick researchers but instead asks the independent Arctic Research Icebreaker Consortium (ARICE) to choose participants based on submissions.

The idea, says the vessel’s science officer on this voyage, Daphné Buiron, is to make the process transparent and minimise the appearance of greenwashing. “Yes, this alliance may deliver a positive public image for the company, but this ship shows we do real science on board,” she says. The labs will improve over time, adds Decamus, as the ship amasses more sophisticated equipment.

Research scientists and tourist vessels don’t typically mix. The former, wary of becoming mascots for the cruise lines’ sustainability marketing efforts, and cognisant of the less-than-pristine footprint of many vessels, tend to be wary. The cruise lines, for their part, see scientists as potentially high maintenance when paying customers should be the priority. But there seemed to be a meeting of the minds, or at least a détente, on Le Commandant Charcot.

“We discuss this a lot and are aware of the downsides, but also the positives,” says Franz von Bock und Polach, head of the institute for ship structural design and analysis at Hamburg University of Technology, specialising in the physics of sea ice. Not only does Charcot grant free access to these remote areas, but the ship will also collect data on the same route multiple times a year with equipment his team leaves on board, offering what scientists prize most: repeatability. “One transit doesn’t have much value,” he says. “But when you measure different seasons, regions and years, you build up a more complex picture.” So, more than just a research paper: forecasts of ice conditions for long-term planning by governments as the Arctic transforms.

Nils Haëntjens, from the University of Maine, is analysing five-millilitre drops of water on a high-tech McLane IFCB microscope. “The instrument captures more than 250,000 images of phytoplankton along the latitudinal transect,” he says. Charcot has doors in the wet lab that allow the scientists to take water samples, and in the bow, inlets take in water without contaminating it. Two freezers can preserve samples for further research back in university labs.

Even though the boat won’t stop, the captain and chief engineer clearly want to make the science missions work. Marchesseau dispatches the helicopter with the researchers and their gear 100 kilometres ahead, where they take core samples and measurements. I spot them in their red snowsuits, pulling sleds on an ice floe, as the boat passes. Startled to see living-colour humans on the ice after days of monochrome, I feel a pang of jealousy as I head for a caviar tasting.

The only other humans we encounter on the journey north are aboard Fifty Years of Victory, the Russian icebreaker. The 160-metre orange- and-black leviathan reached the North Pole a day earlier—its 59th visit—and is on its way back to Murmansk. It’s a classic East meets West moment: the icebreaker, launched just after the collapse of the Soviet Union, meeting the new standard of polar luxury.

The evening before Bastille Day, Le Commandant Charcot arrives at the North Pole. Because of the pinpoint precision of the GPS, Marchesseau has to navigate back and forth for about 20 minutes—with a bridge full of passengers hushing each other so as not to distract him—until he finds 90 degrees north. That final chaotic approach to the top of the world in the grey, windswept landscape looks like a kid’s Etch A Sketch on the chartplotter, but it is met with rousing cheers. The next morning, with good visibility and light winds, we spill out onto the ice for the celebration, followed by a polar plunge.

As guests pose in front of flags and mile markers for major cities, the naturalist guides, armed with rifles, establish a wide perimeter to guard against polar bears. The fearless creatures are highly intelligent, with razor-sharp teeth, hooked claws and the ability to sprint at 40 km/h. Males average about three metres tall and weigh around 700 kilos. They are loners that will kill anything—including other bears and even their own cubs. Cathy and I walk around the far edges of the perimeter to enjoy some solitude. Looking out over the white landscape, I know this is a milestone. But it feels odd that getting here didn’t involve any sweat or even a modicum of discomfort.

The rest of the week is an entirely different trip. On the return south, we see a huge male polar bear ambling on the ice, looking over his shoulder at us. It is our first sighting of the Arctic’s apex predator, and everyone crowds the observation lounge with long-lensed cameras. The next day, we see another male, this one smaller, running away from the ship. “They have many personalities,” says Steiner Aksnes, head of the expedition team, who has led scientists and film crews in the Arctic for 25 years. We see a dozen on the return to Svalbard, where 3,000 are scattered across the archipelago, outnumbering human residents.

The last five days we make six stops on different islands, travelling by Zodiac from Charcot to various beaches. On Lomfjorden, as we look on a hundred yards from shore, a mother polar bear protects her two cubs while a young male hovers in the background. On a Zodiac ride off Alkefjellet, the air is alive with birds, including tens of thousands of Brünnich’s guillemots as well as glaucous gulls and kittiwakes, which nest in that island’s cliffs, while a young male polar bear munches on a ring seal, chin glistening red.

On this part of the trip, the expedition team, mostly 30-something, free-spirited scientists whose areas of expertise range from botany to alpine trekking to whales, lead hikes across different landscapes. The jam-packed schedule sometimes involves three activities per day and includes following the reindeer on Palanderbukta, seeing a colony of 200 walruses on Kapp Lee, hiking the black tundra of Burgerbukta (boasting 3.8-cm-tall willows—said to be the smallest trees in the world and the largest on Svalbard—plus mosquitoes!), watching multiple species of whales breaching offshore, and kayaking the ice floes of Ekmanfjorden. Svalbard is a protected wilderness area, and the cruise lines tailor their schedules so vessels don’t overlap, giving visitors the impression they are setting foot on virgin land.

Chances to experience that sense of discovery and wonder, even slightly stage-managed ones, are dwindling along with the ice sheet and endangered wildlife. If a stunning trip to a frozen North Pole is on your bucket list, the time to go is now.

PARADIGM SHIP

For those studying polar ice, a berth aboard Le Commandant Charcot is like a winning lottery ticket. “This cruise ship is one of the few resources scientists can use, because nothing else can get there,” says G. Mark Miller, CEO of research-vessel builder Greenwater Marine Sciences Offshore (GMSO) and a former ship captain for the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). “Then factor in 80 percent of scientists who want to go to sea, can’t, because of the shortage of research vessels.”

Both Ponant and Viking have designed research labs aboard new expedition vessels as part of their sustainability initiatives. “Remote areas like Antarctica need more data—the typical research is just single data points,” says Damon Stanwell-Smith, Ph.D., head of science and sustainability at Viking. “Every scientist says more information is needed.” The twin sisterships Viking Octantis and Viking Polaris, which travel to Antarctica, Patagonia, the Great Lakes and Canada, have identical 35-square-metre labs, separated into wet and dry areas and fitted out with research equipment. In hangars below are military-grade rigid-hulled inflatables and two six-person yellow submersibles (the pair on Octantis are named John and Paul, while Polaris’s are George and Ringo). Unlike Ponant, Viking doesn’t have an independent association choose scientists for each voyage. Instead, it partners with the University of Cambridge, the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, and NOAA, which send their researchers to work with Viking’s onboard science officers.

“Some people think marine research is sticking some kids on a ship to take measurements,” says Stanwell-Smith. “But we know we can do first-rate science—not spin.” Other cruise lines are also embracing sustainability initiatives, with coral-reef-restoration projects and water-quality measurements, usually in partnership with universities. Just about every vessel has “citizen-scientist” research programs allowing guests the opportunity to count birds or pick up discarded plastic on beaches. So far, Ponant and Viking are the only lines with serious research labs. Ponant is adding science officers to other vessels in its fleet. As part of the initiatives, scientists deliver onboard lectures and sometimes invite passengers to assist in their research.

Given the shortage of research vessels, Stanwell-Smith thinks this passenger-funded system will coexist nicely with current NGO- and government-owned ships. “This could be a new paradigm for exploring the sea,” he says. “Maybe the next generation of research vessels will look like ours.”

You may also like.

Shifting into Neutral

How to Rock a Neutral Selection of Menswear This Autumn.

Model, designer and international jet-setter Johannes Huebl dons autumn’s most refined looks and shares his style insights gleaned from years in front of the camera. Styled by Alex Badia and photographed by Feb Daemen in Barcelona, Huebel’s simple advice rings true.

“I like a natural colour palette and wear monochrome a lot. I tend to stick to no more than two textures in an outfit: a cashmere overshirt and corduroy trousers, for example,” says Huebel, reflecting on his signature style which is captured well in this Autumnal photoshoot.

“Attitude—and a fashionably relaxed mindset— is the secret to wearing clothes like these. The comfort and quality put me at ease.”

Massimo Alba hand-brushed-cashmere sweater, $1,440; Begg & Co cashmere scarf, $870; preowned Blancpain Villeret watch $34,720

L.B.M 1911 wool sweater, $595; Officine Générale wool pants, $995.

Kiton cashmere and silk overshirt, $10,065; Ahlem acetate sunglasses, $780; Rolex x Bamford Watch Department watch (model’s own)

Bally cotton and poly trench, $3,605; Brioni cashmere and silk shirt, $5,895, and cashmere and silk turtleneck, $2,380: Stòffa wool pants, $795.

Louis Vuitton wool double- breasted Pont Neuf suit jacket, $5,215, and wool cigarette pants, $1,650; Connolly cashmere and silk T-shirt, $680; Jacques Marie Mage sunglasses, $1,210.

“My most valuable hacks: get your trousers hemmed so they fit right, avoid anything too tight, and align your colour palette. And don’t overthink it—a dark-navy suit never fails.”

Altea technical-wool jacket, $1,300; Officine Générale cotton shirt, $430.

“Proportion and fit are all-important.I’ve learned that from designers and tailors over the last 20 years.”

Valstar suede jacket, $4,050; Louis Vuitton cotton T-shirt, $855; Lardini wool and cashmere pants, $1,275; John Lobb suede loafers, $2,720.

Loro Piana blazer, $7,560, sweater, $2,495, and pants, $2,190, all in cashmere and wool; John Lobb leather boots, $2,995.

Zegna shetland-wool jacket, $5,215, shetland-wool shirt, $6,275, and pure-wool pleated trousers, $2,250; John Lobb suede loafers, $2,720.

Altea technical-wool jacket, $1,300; Officine Générale cotton shirt, $430.

Model: Johannes Huebl

Senior market editor and casting: Luis Campuzano Hair and makeup artist: Mónica Marmo

Photo assistant: Paolo Caponetto

Executive producer: Rebecca Watson

Production assistants: Nikita Klepach, Marc Gejo Photo director: Irene Opezzo

You may also like.

17/04/2024

18/04/2024

Forever Leather

Furnishings wrapped or accented with classic, cognac-coloured hide create a patina that works with any aesthetic.

Onsen, Gandia Blasco

As the textile industry makes technological advances, traditional outdoor furniture made from iron, wicker and teak seems ever so throwback-y and, dare we say, inconvenient and even uncomfortable. Gandia Blasco’s Mediterranean roots and architectural approach shine in its Onsen collection of garden furniture. Luxe synthetic-leather straps wrapping a tubular stainless-steel structure paired with long-wearing cushions in a similar shade lend new life to the idea of living with leather outdoors. From about $4,425; soft mat about $620, warm mat about $810; Onsen, Gandia Blasco

Gabri, Bolzan

The pared-down, leggy look of these tripod tables packs a functional punch without foregoing refinement. Designed by Matteo Zorzenoni for Bolzan and made in Italy, the Gabri’s leather-bound frames with subtle topstitching and semicircular notches recall desktop accessories of an analog age. The dark tops with touches of chalky veining are thoroughly of this century: made from neolith stone, they’re temperature-resistant and waterproof, so go ahead and place your martini where you will. Small, about $1,735; large, about $2,603; Bolzan.com

Zenius Lines Giobagnara

Giobagnara’s leather-encased Nespresso machine with vertical- or diamond-quilted detailing is genius in its unfussy application. The leather suits the product; the design channels the look of a luxury Italian sports car. The brand began with the Bagnara family producing household items in 1939, before moving into the luxury realm in the ’70s. Giorgio Bagnara changed its name to B. Home Interiors in 1999 and to the eponymous Giobagnara in 2014. If you like your home appliances with liberal leather detailing, it’s one to follow. About $7,900; Artemest.com

Vague, Tonucci Collection

Fun house–meets-Baroque in this softly symmetrical, wall-mounted mirror that playfully beckons you into another dimension (and will bounce beautiful light around the room). Designed by Viola Tonucci, who took the reins of Tonucci Collection from her father last year, the thick, leather-covered frame introduces architectural interest and a hint of levity to a room, be it traditional or modern. About $8,050; Tonucci.com

DS-707, de Sede

Given Philippe Malouin’s propensity for experimentation, it’s no wonder that Swiss furniture firm de Sede took a whole new approach in manufacturing Malouin’s DS-707 design. He began by noodling around with foam, folding it this way and that before settling on the serpentine shape. Although the silhouette made de Sede wary—creating it required the team to manipulate leather in a manner that could leave it less supple— the project prevailed with great success. The system itself invites experimentation as customers can configure the components to their heart’s content. From $30,450; deSede.com

You may also like.

The Perfect Fit

From garden to park, feel the burn with Ethimo’s slick access-all-areas gym.

Not feeling your Peloton?

Hit the gym outside with garden furniture brand Ethimo and Studio Adolini’s open-air “fitness room”, OUT-FIT. Measuring 250 x 250 cm and 280 cm in height, but designed to be adaptable to any open-air location, OUT-FIT is made entirely in teak and rust-finish metal, and comes with a series of equipment for bodyweight training.

Let’s do this. ethimo.com

You may also like.

18/04/2024

By Zeb Daemen

18/04/2024

Don’t Ride This Wave ….*unless your name is Robinson, Slater or Moore.

The 2024 Olympic surfing comp will be held at Tahiti’s treacherous Teahupo’o. Going for gold could be deadly.

It’s day two of the 2023 Tahiti Pro Surf Competition. I’m perched on the roof of a VIP boat around 100 metres from Teahupo’o, one of the world’s most dangerous waves. American Surf icon Kelly Slater has just been swallowed by a heaving wall of turquoise water. I’m so close to the action that when he’s finally spit out from the ride, my face gets misted in ocean spray. Below me, Australian Jack Robinson, who will go on to win the event, sits on the edge of the boat performing breathing exercises ahead of his heat. Around me, a flotilla of kayaks, jetskis, surfboards, and small vessels bobs in the channel, acting as a floating stadium for fans.

For many of the competitors—and the 1,400-odd residents of the wave’s namesake village—this year’s contest is a dress rehearsal for an event with a far larger global profile in a few months’ time. While many of the world’s top athletes will travel to France in July for the 2024 Paris Olympic Games, the most talented surfers will head here, to the southwest corner of Tahiti island’s small peninsula, Tahiti Iti, to vie for gold at Teahupo’o in just the second surf competition in Olympic history.

In keeping with the limit of two surfers per gender, per nation, the Australian flag will be flown by Ethan Ewing (No. 2 in the World Surf League rankings at the time of writing) and the aforementioned Robinson (No. 5) in the men’s category, and Tyler Wright (No. 3) and Molly Picklum (No. 5) in the women’s. On this form, hopes of a homegrown medal haul are high.

Olympic officials could have chosen a site off the coast of France, such as the surf towns of Biarritz or Hossegor, but historically, Mother Nature brings more sizable waves to Tahiti at this time of year. Plus, surfing has deep cultural ties to the region. The sport originated in Polynesia and dates as far back as the 12th century; it was practiced by Polynesian royalty. Teahupo’o is also a world-class wave that challenges the mental and physical prowess of even the most experienced competitors. The high risk of surfing this spot guarantees thrills that officials anticipate will boost viewership.

Located in the gin-clear waters of the South Pacific with a background of mountains that appear to be draped in jade-green crushed velvet, Teahupo’o (pronounced TAY-a-hoo-poh-oh) is one of the sport’s most infamous swells. (Its name loosely—and cheerily—translates to “place of skulls”.) According to Memoirs of Marau Taaroa, Last Queen of Tahiti, printed in 1893, the first person to surf it was actually a woman from the island of Raiatea, in the 19th century. Not until the 1980s did anyone dare attempt it again, with the first competition hosted in the late 1990s. Former pro turned filmmaker Chris Malloy has called it “the wave that has changed surfing forever”.

In the right conditions, Teahupo’o can tower upwards of six metres. That may sound small compared to the monster-size Jaws in Maui or Nazaré in Portugal—which can climb as high as 25 metres—but it’s not the height that makes Chopes, as the wave is lovingly called, so special. It’s the weight. When surfers describe a wave as heavy, they’re referring to its combination of a thick lip (the powerful section that starts to curl over) and the amount of water surging behind it.

Like most of the surf breaks found throughout French Polynesia, Teahupo’o is a reef break, meaning the water spills over the surface of knife- sharp coral. Chopes is unique because around 50 metres beyond the reef, the ocean drops more than 15 metres. As swells come toward the shore, the transition from deep water causes them to jack up over the coral before quickly crashing down with tremendous force.

“The reef evolved perfectly in order to absorb the wave’s energy in the shortest distance possible to create this natural wonder,” surf superstar Laird Hamilton tells Robb Report. “It’s a wave that stands straight up and creates a huge barrel. It’s one of the greatest waves on Earth.” In 2000, Hamilton rewrote surfing history when he rode what has been dubbed the Millennium Wave here. Up until then, Teahupo’o was considered too perilous to attempt when it reached a certain size. Hamilton, a pioneer of tow surfing, had a jetski pull him into what is still considered one of the heaviest waves ever ridden. Surfer magazine published a memorable cover of him getting barrelled with just the words “Oh my god…” because the feat was so dangerous.

In places, the reef lurks just 50 centimetres beneath the water’s surface, and the lip can act like a liquid guillotine if it clamps down before a surfer exits the hollow tube of the wave, known as the barrel. Had Hamilton wiped out, he wouldn’t have had an escape route.

I’m an avid amateur surfer and live on Maui part-time to take advantage of Hawaii’s waves, but even on a gentle day, I wouldn’t attempt Teahupo’o. Teahupo’o village has a water-safety patrol that watches over athletes during contests. Still, a handful of surfers have lost their lives here, and many go home with serious battle wounds. In August last year, during a practice session for the Tahiti Pro, Ethan Ewing fractured two vertebrae in his back after crashing out in solid, but average, six-foot waves—an accident that arguably cost him top spot in the world rankings.

In classic gung-ho-surfer fashion, though, the Queenslander was back in the water at Teahupo’o three months later, one eye still resolutely fixed on Olympic glory. “Definitely more anxious than excited heading back to Tahiti after hitting the reef really hard last time,” he posted on his Instagram account. “Teahupo’o is still seriously intimidating, but I feel like I’ve made some steps in the right direction.”

Unless you surf, Tahiti Iti probably isn’t on your radar. Starting from the largest town of Taravao, the south-coast road ends at the village of Teahupo’o, hence its nickname, the End of the Road. The community, just 500 metres from the wave, is the antithesis of the glitz and glamour of Paris or even nearby Bora Bora. This is a slice of tropical paradise that has somehow evaded development. To reach the contest each day, I park at the end of the road, then walk over a one-lane bridge and follow a sandy path that passes local homes.

“All of your senses are heightened here,” former world surf champion C. J. Hobgood tells me when I run into him at the event. “It’s not just the wave—it’s the island. Everything looks five- dimensional. Mountains seem stacked on mountains and glow a vivid green. You turn to the right and these bluer-than-blue waves are breaking. Then a rainbow might appear in the sky. The raw beauty is overwhelming to take in when you first arrive.”

Surfers talk of feeling the mana, a Polynesian word for spiritual energy, here. Jack Robinson even referenced it after his victory in the Tahiti Pro. It may sound woo-woo, but I undoubtedly feel something when I arrive after a 90-minute drive south-west from the hotel-lined harbour of Tahiti Nui, the island’s larger, more developed area. Tahiti Iti’s empty beaches and waterfall-riddled lush interiors remind me of a quieter, more vibrant version of Hana, a little corner of Maui with just one hotel, a handful of restaurants and kilometres of untamed nature. In an era of over-tourism, this kind of purity comes with a trade-off: You won’t find five-star hotels or celebrity-chef restaurants on Tahiti Iti. In fact, it doesn’t have any hotels at all—and won’t be opening any ahead of the Games.

Locals have been adamant that Olympic infrastructure remains minimal. The proposed construction of a three-storey judging tower directly on the reef at Teahupo’o has been a major concern among residents and environmental groups. The one Olympic improvement locals welcome is a new bridge that will connect to the beach in front of Chopes.

I check into Villa Mitirapa, newly built in the rural community of Afaahiti, a 25-minute drive from Teahupo’o. Giant carved wooden doors lead to an open-air living room, a plunge pool and views of the lagoon, and every evening a chef drops by with a delicious preparation of the catch of the day. In the village of Teahupo’o, you’ll find family-owned guesthouses such as Vanira Lodge, a collection of three bungalows tucked up in Te Pari (“the cliffs” in Tahitian), as well as A Hi’o To Mou’a, a B&B run by the proprietor of hiking outfit Heeuri Explorer.

Pro surfers are typically hosted by the same local families year after year. (During the Olympics, athletes will be housed on a ship anchored in a sandy area offshore to avoid damaging the seabed.) Hobgood tells me he made visits to his “adopted Tahitian family” for nearly two decades. For the past five years, he has come to Teahupo’o to help coach reigning Olympic champ, Hawaiian Carissa Moore and now stays with her adopted family. “They take us on hikes you’d otherwise never know how to access and have rich stories about the place,” he says. “And everything they prepare for us at meals, from the passion-fruit jam to the chilli sauce, is homemade.”

The next big thing being “adopted” by a Tahitian family is hiring Raimana van Bastolaer as your guide. For a first-time visitor, Tahiti Iti can be far harder to access than other islands, which is perhaps why so few people explore the peninsula. You need a local to reveal where to go, and van Bastolaer makes you feel like an insider.

Born and raised in the capital of Papeete, he was one of the first locals to surf Chopes, and over the years, his intricate knowledge of the wave has earned him the nickname the Godfather of Teahupo’o. He was out in the channel with Hamilton the day the American had his historic ride, and John John Florence and Kelly Slater are among the surfers who stay with him when they’re in town. Van Bastolaer even did a stint as a part-time coach at Surf Ranch, Slater’s central California wave park. Thanks to his non-stop pursuit of a good time, everyone wants to be around him. Now 48, the stockily built, dauntingly athletic van Bastolaer has become the go-to guide for visitors ranging from Julia Roberts, Margot Robbie and Jason Momoa to Mark Zuckerberg and Prince Harry. “I get to yell at princes and CEOs,” he jokes. “I’m out in the water with them telling them when to pop up and paddle. And they love it.”

Tahiti’s unofficial ambassador lives and breathes surfing. Through his company, Raimana World, he takes just one or two guests at a time on private curated surf tours throughout French Polynesia’s two central archipelagoes: the Society Islands (which are home to Tahiti) and the Tuamotus; he plans to add Fiji soon. Some of his clients base themselves on their own yachts or charter one through Pelorus. The yacht specialist’s Tahiti portfolio includes the 77-metre La Datcha, which has two helipads, a submersible and a spa.

Other clients he directs to exclusive properties, such as Motu Nao Nao, a new 25-hectare private-island resort in the cerulean lagoon of Raiatea with just three enormous villas crafted from coral, wood, and shells. A roving bar bike delivers custom cocktails to guests as they explore the island, and the French chef, inspired by Asian and North African cuisine, prides himself on never repeating a dish, no matter how long guests stay.

Van Bastolaer gets only one or two clients a year experienced enough to be coached into a barrel at Teahupo’o. “Most just want to get close to the wave to feel its energy and hear it roar,” he says. “That’s enough to give you an adrenaline rush.” Locals are incredibly protective of their surf spots, and van Bastolaer stays away from popular breaks. “Out of respect, I don’t take clients out if there are more than a few people in the water. Luckily, I have access to toys that get us away from the crowds.” He island-hops by helicopter, yacht or jet boat, then transports guests to surf breaks via high-speed RIB (rigid inflatable boat) or jetski. Most days average two to three hours of surfing, and he sprinkles in other activities such as snorkeling, whale watching (July to November) and barbecues at his house.

Papara, the beautiful black-sand beach where van Bastolaer honed his skills, 45 minutes from Teahupo’o, will be turned into a fan viewing zone with jumbo screens during the Olympics. Papara is one of the most forgiving surf breaks in Tahiti, and I head here to longboard. La Plage de Maui, a simple restaurant with sandy floors, plastic chairs and lagoon vistas, becomes my daily après-surf spot. Located in West Taiarapu, 40 minutes east of Papara, with nothing but coastal road and local homes in between, this humble spot sits next to Maui Beach, one of the only white-sand beaches on the whole island. This stretch may be Tahiti Iti’s best-kept secret.

After a barefoot walk along the shore, I don’t bother to put my shoes back on before heading into the restaurant, where servers proudly sport Tahiti Pro T-shirts and posters of pros hang on the walls. At a waterfront table, I spot rainbow-hued parrotfish and Moorish idol in the glassy lagoon. I’m pretty sure I could live on a diet of local Hinano beer and poisson cru, Tahiti’s national dish of raw fish marinated in lime juice and coconut milk. My final day, I ask my waitress if she’s concerned the Olympics might overexpose this laid-back, oft-forgotten enclave. She just laughs in reply.

On the drive back to my villa, I remember what van Bastolaer told me when we were introduced a year ago: Tahiti Iti’s specialness is lost on those seeking overwater bungalows or nightlife. It’s a place you can’t know in a day. The island reveals itself to you slowly. And even when van Bastolaer is your host, he won’t give away all its secrets.